Reader's Choice

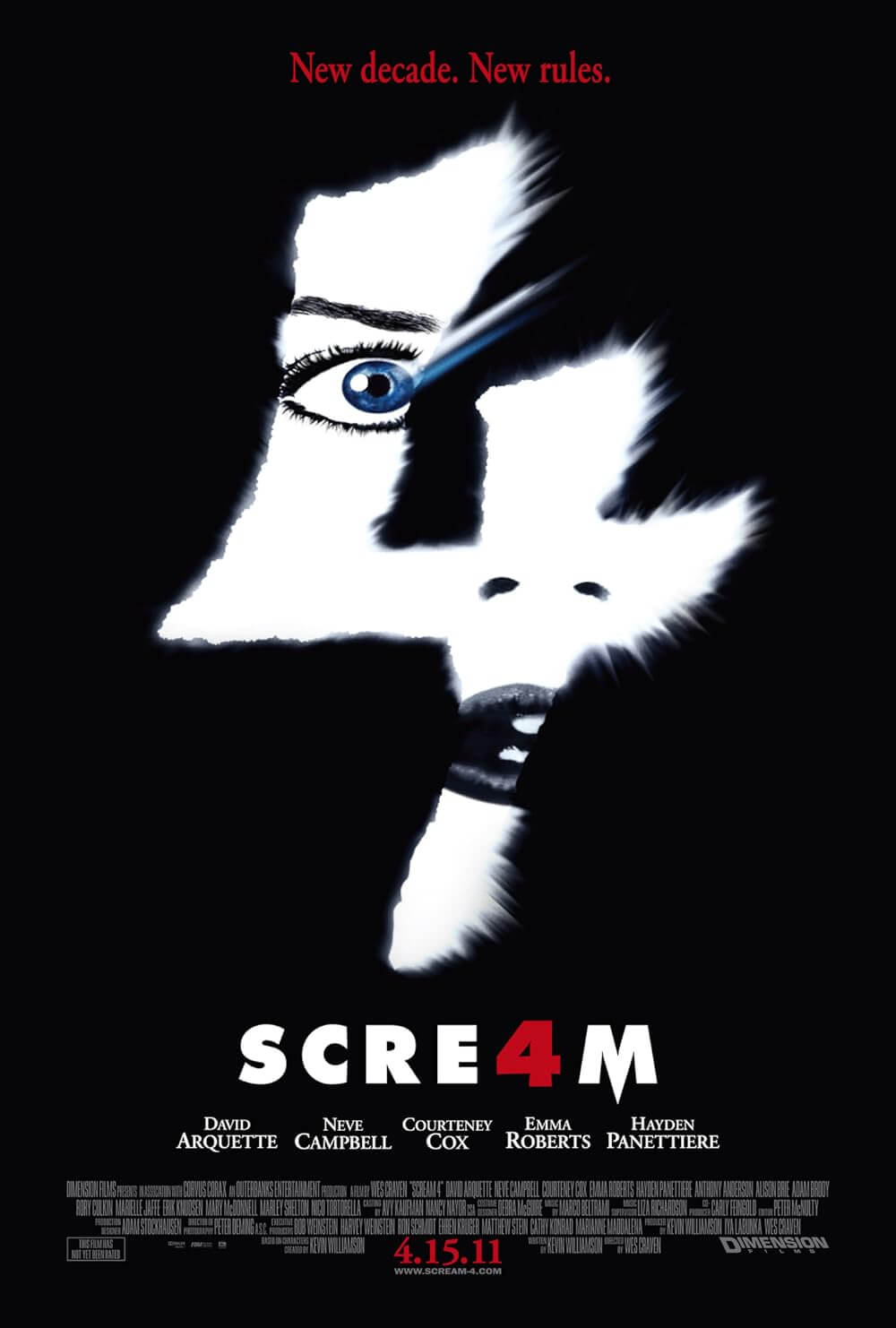

Scream 4

By Brian Eggert |

Scream 4 has the perfect opening to remark on a culture so saturated in meta-ness, irony, and social media that reality no longer has any meaning. In a familiar setup, two teens (Shenae Grimes, Lucy Hale) fall victim to a call and cyber-stalking from Ghostface. The taunts escalate until two Ghostfaces appear and slay the girls in a bloody scene. But this is just the opening scene of Stab 6, the franchise-within-a-franchise that now has more sequels than Scream. Couched in front of a TV, Anna Paquin and Kristen Bell—celebrities almost as recognizable as Drew Barrymore in the original—pause Stab 6 to debate the current trends in horror. But Bell grows tired of Paquin’s harping and plunges a knife into her stomach. However, this is the opening of Stab 7, watched by two lesser-known teens (Britt Robertson, Aimee Teegarden), who discuss the expansive mythology of the Stab series before, of course, Ghostface arrives, chases them around the house, and kills them both. Whereas the earlier Scream movies prove more interested in the mirroring relationship between real life and art, Scream 4 continues that trend, except with an interest in post-modernism folding over on itself in the desperate need for horror franchise reinvention. But the 2011 sequel also critiques fandom, social media, and the lengths some people will go for attention.

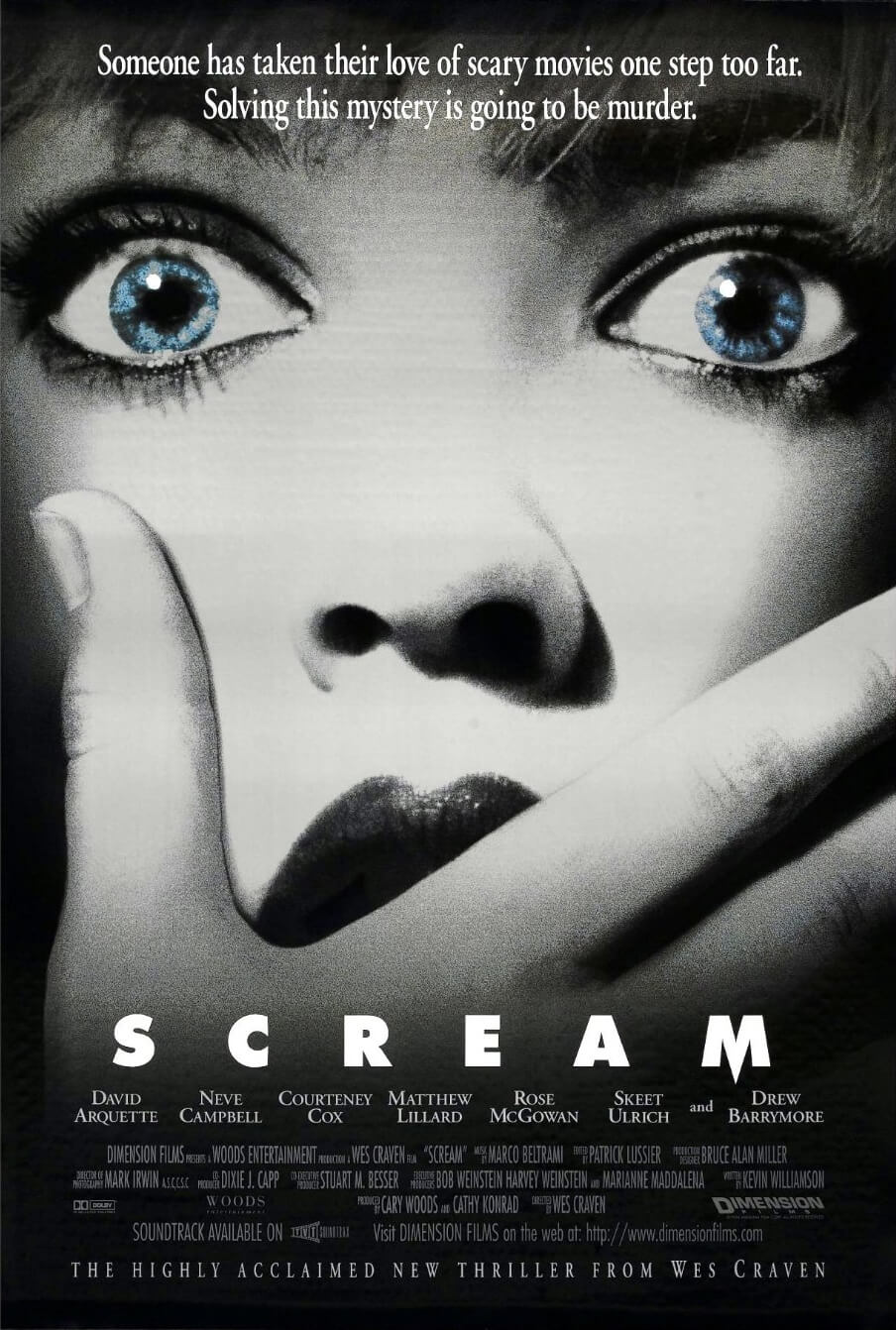

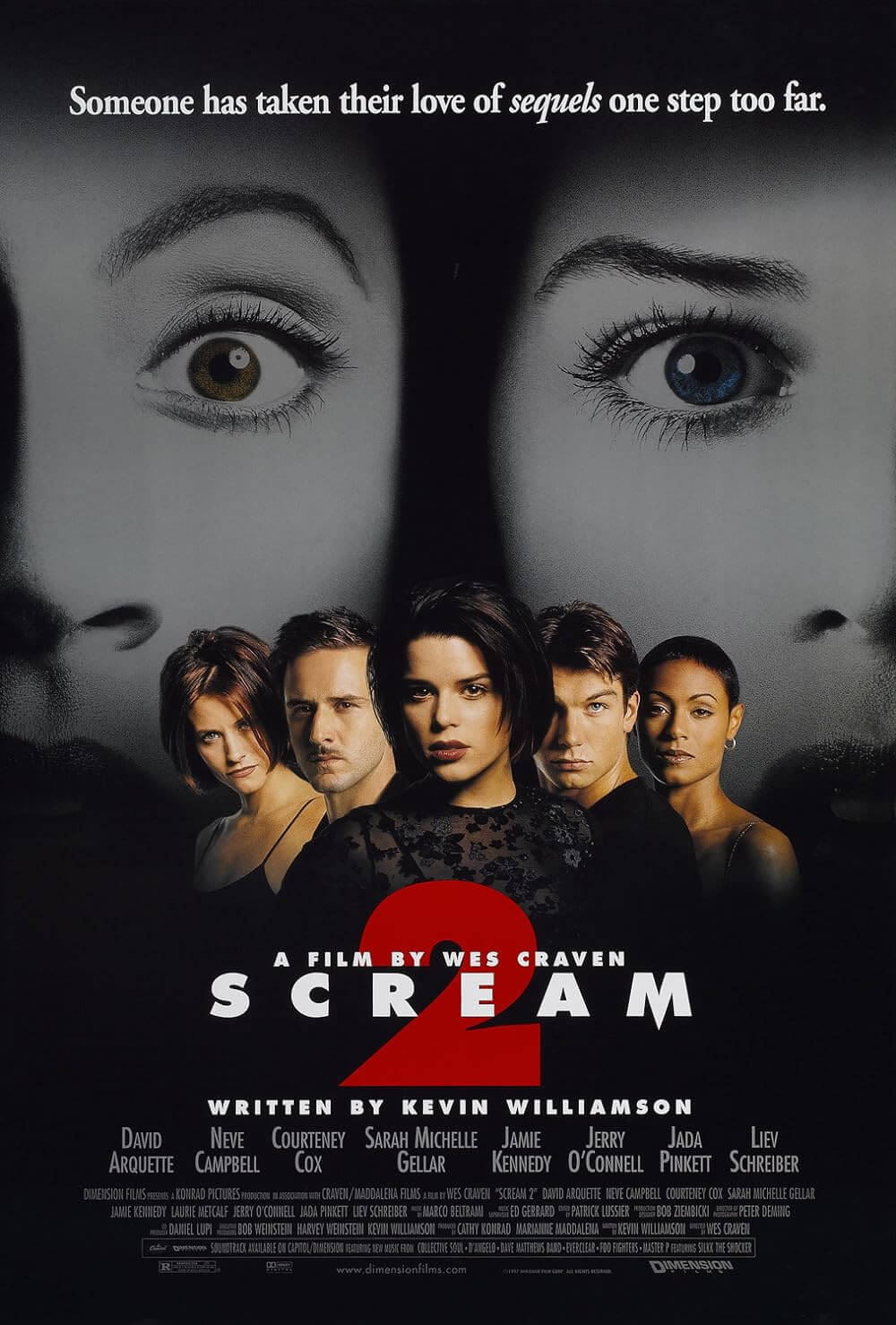

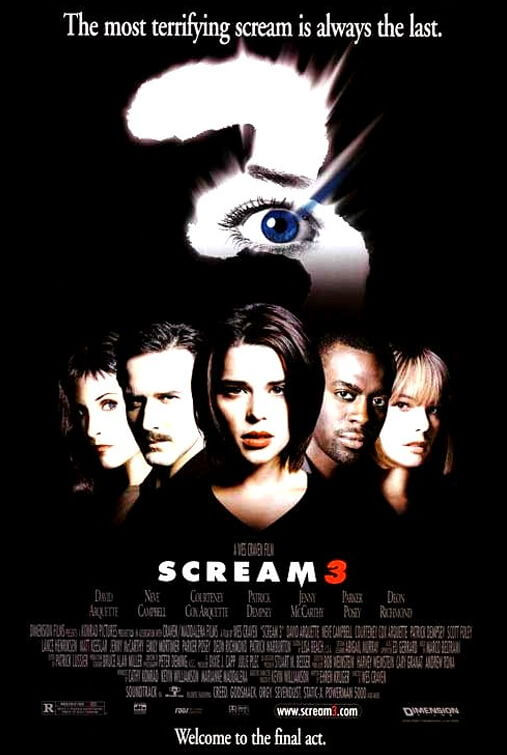

The fourth installment is a back-to-basics sequel, restoring—after the comic departure of Scream 3 (2000)—the franchise’s balance of bloody horror with cinema-savvy discussions, in-jokes, and characters attuned to horror movie clichés. It’s easily the most visceral entry next to the 1996 original, and it crackles with meta-commentary owing to the return of screenwriter Kevin Williamson, who wrote the first two movies but not the third. In the 11 years since Scream 3, the horror genre had barely survived the torture porn craze. Remakes—many of them originally directed by Scream helmer Wes Craven—became the new standard, including The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003), The Hills Have Eyes (2006), Friday the 13th (2009), The Last House on the Left (2009), and A Nightmare on Elm Street (2010). Social media had also begun to dominate everyday life. And with the emergence of reality television celebrities, such as the Kardashians, who became famous for no other reason than being famous, the distinction between reality and mediated life began to blur. Scream 4 comments on these trends, even while attempting a legacy sequel and soft reboot for a new generation—or, as 2022’s Scream would call it, a “requel.”

Around 2009, about the time Wes Craven’s My Soul to Take arrived in theaters, talk of a fourth Scream movie started to materialize, with Dimension head Bob Weinstein claiming the new installment would be a complete remake of the original. Once screenwriter Kevin Williamson boarded the project, he recognized that Scream and its sequels work better than other horror franchises because the audience remained invested in the returning survivors: Sidney Prescott, Gale Weathers, and Dewey Riley. Unlike other horror franchises such as Friday the 13th, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Paranormal Activity, and Saw, which found a circulating cast of characters played by relative unknowns getting haunted and slaughtered to bits, Scream had maintained its original top-billed trio (for the time being, anyway). So, a fresh start for Scream would never work. Williamson convinced Weinstein of this, and Dimension dropped the remake idea in favor of a return to Woodsboro—complete with the original characters joining a new cast of teens and Craven returning as director. Fittingly, Williamson’s script incorporates commentary about the popular trend of remakes and the occasional missteps of long-lasting horror franchises.

Around 2009, about the time Wes Craven’s My Soul to Take arrived in theaters, talk of a fourth Scream movie started to materialize, with Dimension head Bob Weinstein claiming the new installment would be a complete remake of the original. Once screenwriter Kevin Williamson boarded the project, he recognized that Scream and its sequels work better than other horror franchises because the audience remained invested in the returning survivors: Sidney Prescott, Gale Weathers, and Dewey Riley. Unlike other horror franchises such as Friday the 13th, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Paranormal Activity, and Saw, which found a circulating cast of characters played by relative unknowns getting haunted and slaughtered to bits, Scream had maintained its original top-billed trio (for the time being, anyway). So, a fresh start for Scream would never work. Williamson convinced Weinstein of this, and Dimension dropped the remake idea in favor of a return to Woodsboro—complete with the original characters joining a new cast of teens and Craven returning as director. Fittingly, Williamson’s script incorporates commentary about the popular trend of remakes and the occasional missteps of long-lasting horror franchises.

Even with Williamson and Craven back, Scream 4 became more chaotic than any Scream production due to Bob Weinstein’s constant questioning of the script. After the cameras started rolling, Weinstein continued to demand rewrites, prompting disagreements with Craven and Williamson. Eventually, Williamson was contractually obligated to return to the set of his television show, The Vampire Diaries, leaving Ehren Kruger—writer of Scream 3 and credited producer on Scream 4—to handle the uncredited rewrites alongside Craven. An idea involving Gale and Dewey having a baby was written out to avoid the hassle of arranging scenes around a small child; plus, Cox and Arquette, married ten years at that point, had just begun a trial separation that caused some offscreen tension. Additional characters, played by Alison Brie and Aimee Teegarden, were added to boost the body count and give Craven more opportunities to amplify the horror scenes. And Williamson had written a cliffhanger ending that would lead directly into a sequel, but Weinstein worried that the audience might feel robbed, so he scrapped the open-ended conclusion. The continued rewrites throughout the production made the cast and crew feel disjointed, but aside from a loose end or two, the result mainly conceals the behind-the-scenes confusion.

After the excellent opener, Scream 4 picks up in Woodsboro, home of the notorious “Ghostface” murders that spawned Gale Weathers’ bestselling book on the subject, which led to seven Stab movies. Now an author with writer’s block, Gale (Courteney Cox) has settled into a quiet life of marriage to Woodsboro’s sheriff, Dewey (David Arquette). Conveniently enough, the latest strain of Ghostface murders coincides with the return of Sidney (Neve Campbell) to Woodsboro, accompanied by her opportunistic publicist (Brie). Sidney is on a promotional tour for Out of Darkness, her ham-fistedly titled book that insists she has put all three sets of grisly murders behind her. Alongside these veteran survivors from the first Scream, the film introduces a new generation of victims to a new generation of moviegoers. Foremost, Sidney must relive her traumatic experiences through the eyes of her teen cousin, Jill (Emma Roberts), whose friend group has become the latest target of the Ghostface copycat. Meanwhile, Jill’s mother (Mary McDonnell), Sidney’s aunt, resents that no one pays attention to her, being the sister of Maureen Prescott—the person whose death started it all.

Jill’s high school friends, played by a pack of twentysomethings, include all the usual suspects, built from molds established in the original Scream (as the sequels say, it’s always about returning to the original). First, there’s Trevor (Nico Tortorella), Jill’s former boyfriend whose possessive behavior makes him a likely candidate. Next, two horror-movie-obsessed cineastes, the spaced-out Charlie (Rory Culkin) and the constant live-streamer Robbie (Erik Knudsen), use their encyclopedic movie knowledge to spout theories about the killer, even though they’re also viable possibilities. Around the midpoint, Charlie and Robbie host an ill-advised Stab-a-Thon event, which the killer inevitably crashes. Hayden Panettiere is charming as Jill’s friend Kirby, a closet horror nut. Absent, as ever, are parents, who disappear so their children might be slaughtered without much effort. At least there’s an increased presence of Woodsboro police, including Deputy Hicks (Marley Shelton), who doesn’t hide her crush on Dewey. Anthony Anderson and Adam Brody also appear as cops posted to Jill’s house. As usual, everyone’s a suspect.

Jill’s high school friends, played by a pack of twentysomethings, include all the usual suspects, built from molds established in the original Scream (as the sequels say, it’s always about returning to the original). First, there’s Trevor (Nico Tortorella), Jill’s former boyfriend whose possessive behavior makes him a likely candidate. Next, two horror-movie-obsessed cineastes, the spaced-out Charlie (Rory Culkin) and the constant live-streamer Robbie (Erik Knudsen), use their encyclopedic movie knowledge to spout theories about the killer, even though they’re also viable possibilities. Around the midpoint, Charlie and Robbie host an ill-advised Stab-a-Thon event, which the killer inevitably crashes. Hayden Panettiere is charming as Jill’s friend Kirby, a closet horror nut. Absent, as ever, are parents, who disappear so their children might be slaughtered without much effort. At least there’s an increased presence of Woodsboro police, including Deputy Hicks (Marley Shelton), who doesn’t hide her crush on Dewey. Anthony Anderson and Adam Brody also appear as cops posted to Jill’s house. As usual, everyone’s a suspect.

Liberated from the restrictions placed on him during Scream 3, Craven delivers several bloody and gasp-inducing deaths, making Scream 4 the scariest since the original. The finale in the hospital, where one of the killers repeatedly punches Sidney in her abdomen’s stab wound, remains impossible to watch without squirming. However, the film doesn’t look like its predecessors; series cinematographer Peter Deming applies a soft-filtered blur effect that makes daylight scenes look like a (bad) dream. Although this visual technique represents a stylistic departure from the first three installments, it might underscore the film’s theme about social media by making the picture look filtered by the then-young Instagram. The aesthetic aligns with Jill and Charlie’s master plan to make a movie out of real-life killings and place them online, even if it means killing their friends. “I don’t need friends,” Jill declares. “I need fans!” So, they don the Ghostface garb as an extreme shortcut to instant fame. In their twisting roles, Roberts is unconvincing as the psychopathic mastermind, whereas Culkin has all the wounded and misguided anger of someone who desperately wants attention.

Craven remarked at the time that the most significant challenge with Scream 4’s script was finding a way to integrate the legacy characters with the newcomers. For their part, Sidney, Gale, and Dewey occupy a peripheral view as the teens are killed, only to become further entangled in the second and third acts. Still, it never feels like their movie, even if they’re the heroes by the end credits. Campbell’s protagonist has less of an arc this time around, even though her screen presence goes a long way to create that Scream feeling. What’s more, given the increasing popularity of horror among mainstream viewers, the teens demonstrate a heightened awareness of horror movie rules—practically every teen in the movie could keep up with Jamie Kennedy’s Randy. Even so, they cannot resist staying home alone, going outside to investigate a noise in the dark, or having a party with a killer on the loose. Somehow, their vast movie knowledge makes their reckless teen behavior seem even stupider. But the sheer violent nature of the scenes, especially those with Sidney in the last half-hour, make the sequel feel urgent, as though one of our favorite characters might not survive.

Scream 4’s critical reception was lukewarm to middling, and the box-office performance was even worse. During preproduction, Williamson sketched a loose narrative trajectory that would encompass a new trilogy. But since Scream 4 only managed to make $38 million in domestic grosses—less than half of what its predecessors made—Dimension resolved not to continue with the proposed trilogy. A decade later, James Vanderbilt and Guy Busick would take over as franchise writers, ignoring Williamson’s outline for Scream 5 and 6, for better or worse (by this critic’s estimation, worse). Scream 4 would also be the last franchise entry to include Craven, Williamson, and the Weinsteins. Craven succumbed to a brain tumor in 2015 at age 76, making Scream 4 his final directorial effort. Williamson would serve as executive producer on 2022’s “requel” Scream and its 2023 follow-up Scream VI. And the name Weinstein has become infamous the world over ever since the #MeToo movement exposed Harvey’s sex crimes, leading to his imprisonment for what will be the remainder of his life. Bob has kept out of the spotlight since his brother’s scandal. As a result, Scream 5 and the TV series (2015-2019) feel like fan fiction—a quality they cannot shake, even as they remain self-aware of their faux status.

Scream 4’s critical reception was lukewarm to middling, and the box-office performance was even worse. During preproduction, Williamson sketched a loose narrative trajectory that would encompass a new trilogy. But since Scream 4 only managed to make $38 million in domestic grosses—less than half of what its predecessors made—Dimension resolved not to continue with the proposed trilogy. A decade later, James Vanderbilt and Guy Busick would take over as franchise writers, ignoring Williamson’s outline for Scream 5 and 6, for better or worse (by this critic’s estimation, worse). Scream 4 would also be the last franchise entry to include Craven, Williamson, and the Weinsteins. Craven succumbed to a brain tumor in 2015 at age 76, making Scream 4 his final directorial effort. Williamson would serve as executive producer on 2022’s “requel” Scream and its 2023 follow-up Scream VI. And the name Weinstein has become infamous the world over ever since the #MeToo movement exposed Harvey’s sex crimes, leading to his imprisonment for what will be the remainder of his life. Bob has kept out of the spotlight since his brother’s scandal. As a result, Scream 5 and the TV series (2015-2019) feel like fan fiction—a quality they cannot shake, even as they remain self-aware of their faux status.

Although Scream 4 borders on a remake and attempts to be the same, only different, the writing is sharp, and the young cast is likable, particularly Culkin and Panettiere. It’s also ironic that the story is about the very thing that the Weinsteins wanted to avoid during the production of Scream 3—copycats. But unlike earlier sequels, the killers in Scream 4 have no issues with Maureen Prescott; instead, their motivations are entirely selfish and focused on virality. It’s an example followed by Tragedy Girls (2017), Spree (2020), and others about live-streamers who will kill for online attention and validation. So while Scream 4 boasts the series’ customary movie-within-a-movie (within-a-movie) tricks and self-reflexivity, it also holds a mirror up to its contemporary audience. Best of all, and most importantly, the sequel is thrilling and genuinely shocking at times—a feat not accomplished in any Scream movie since the original. It shows that, even in his 70s, Craven, the Guru of Gore and Sultan of Shock, still had a few tricks up his sleeve.

(Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon and published on March 8, 2023.)

Bibliography:

Maroney, Padriac. It All Began with a Scream. BearManor Media, 2021.

Robb, Brian J. Screams and Nightmares: The Films of Wes Craven. Polaris Publishing, Inc., 2022.

Wooley, John. Wes Craven: The Man and His Nightmares. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2011.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review