Reader's Choice

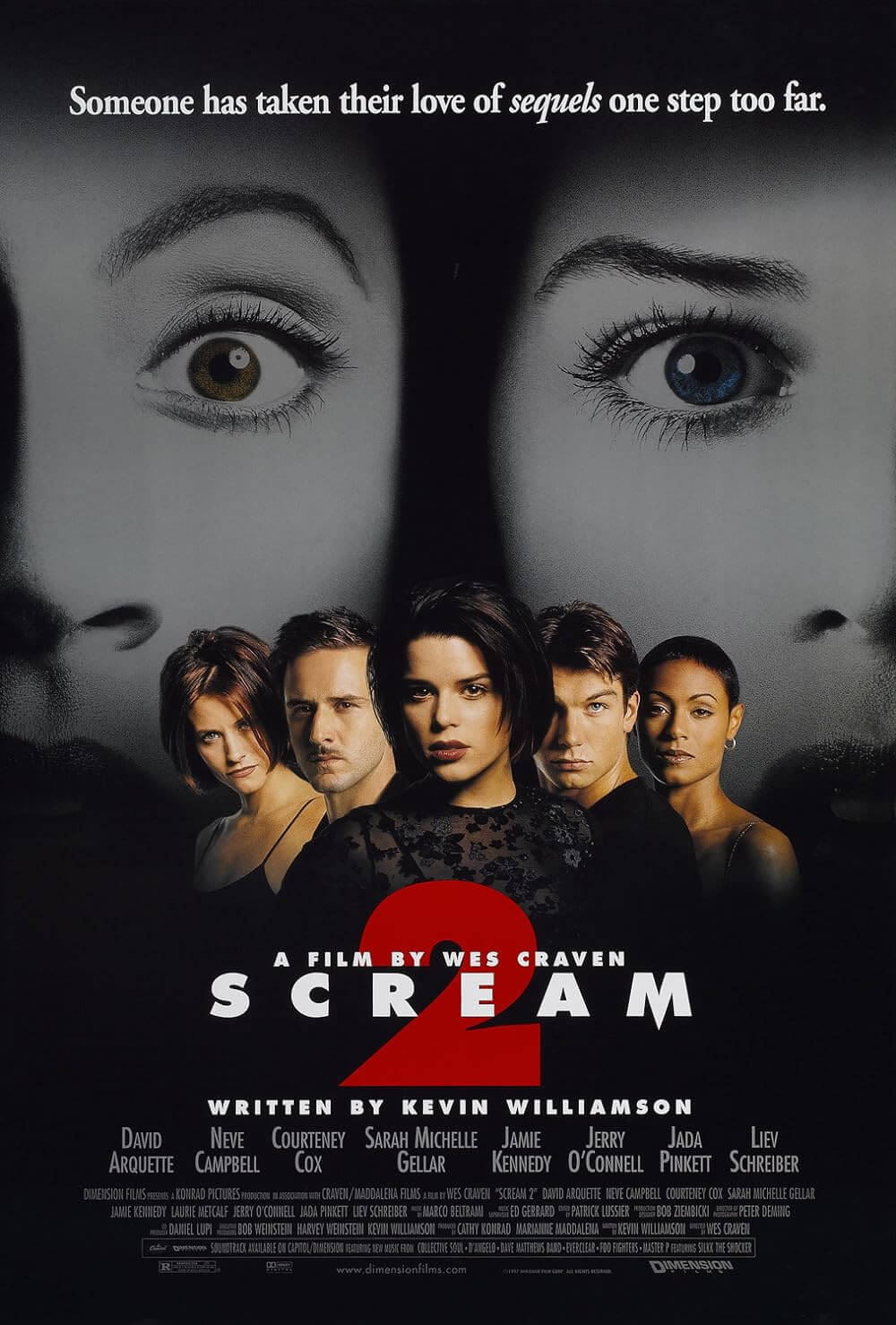

Scream 2

By Brian Eggert |

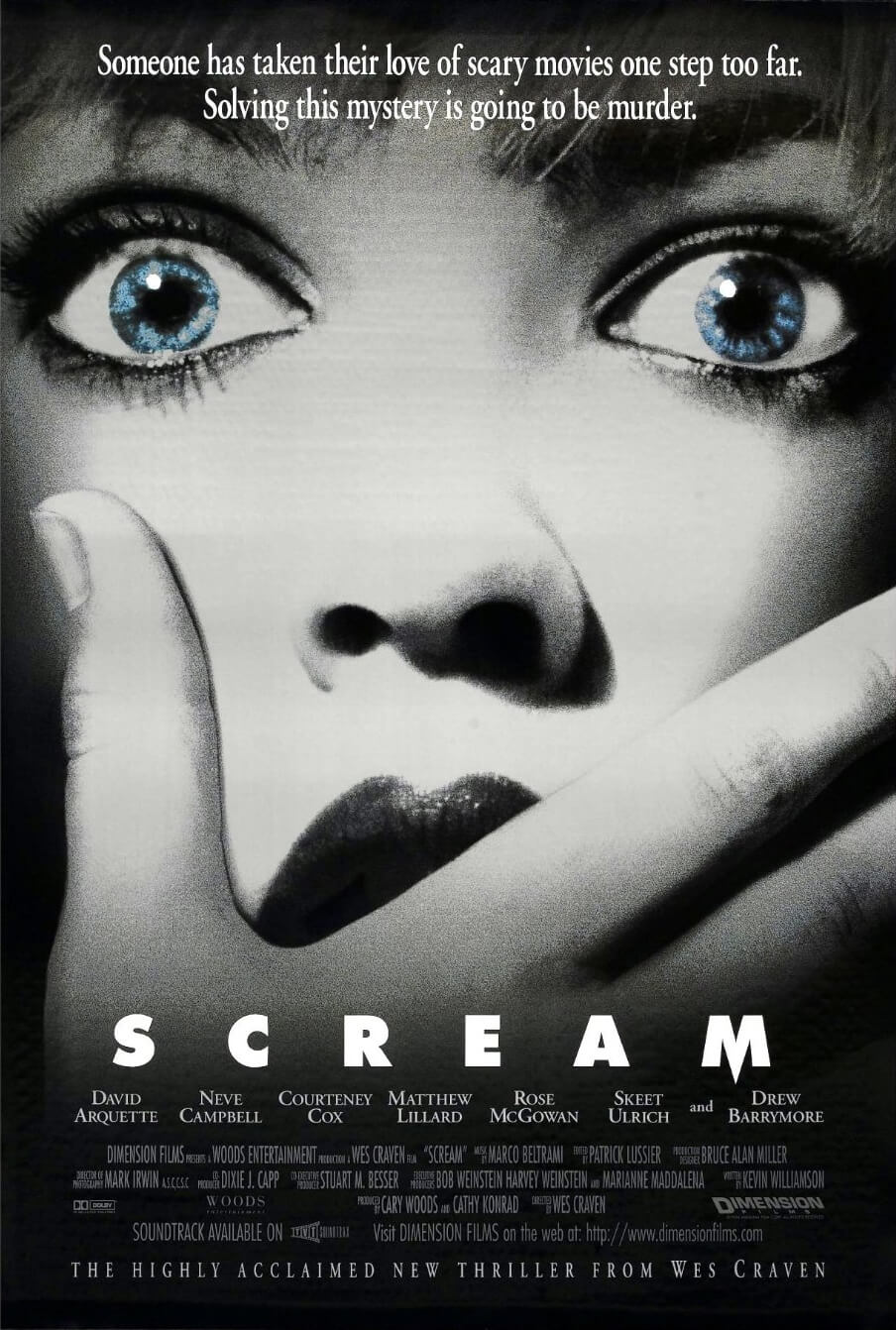

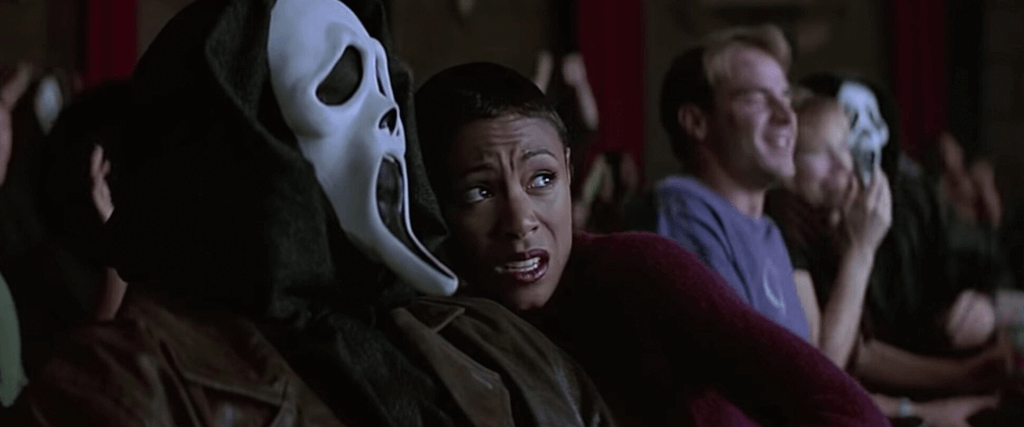

If Scream (1996) opens with one of horror’s most iconic scenes, the sequel features a pre-credits sequence that, like its predecessor, is better than the film that follows it. Two college students, Maureen and Phil, played by Jada Pinkett and Omar Epps, attend a prescreening of Stab, a movie based on the book by opportunistic journalist Gale Weathers (Courteney Cox) about the Woodsboro murders. Phil is enthused, but Maureen is no fan of horror movies. Inside, unhinged moviegoers dressed in Ghostface costumes throw popcorn, holler in the aisles, and wave glow-in-the-dark plastic knives. Why they’re so fanatical about a movie based on a book remains curious. Usually, such zealous behavior accompanies established franchises or repeat midnight madness screenings of beloved cult classics (think Rocky Horror Picture Show), not pre-screenings. But no matter. Soon, a real killer enters the scene, hiding among the many Ghostfaces. After taking out Phil in the restroom, the killer sits beside Maureen and stabs her amid the unruly theater patrons. No one notices the actual violence happening before them until the bloodied Maureen climbs on stage in front of the screen and falls to her death. Then, finally, the crowd notices, and the real screaming begins.

Scream 2’s opening cleverly establishes a few themes. First, the sequel contains a rich narrative thread about art imitating life and vice versa, particularly concerning the Woodsboro murders, the movie about them, and the copycat killer. Second, it continues the notion so vital to Scream, where reality and the movies overlap with the same self-reflexivity of its predecessor. But instead of just commenting on horror movie clichés while simultaneously deploying them to thrilling effect, as in Scream, the sequel also remarks on trends in sequels. Perhaps its most inspired touch of self-awareness is Stab, Scream 2’s movie-within-a-movie—complete with Heather Graham in the Drew Barrymore role and, as grimly predicted in the original, Tori Spelling as Sidney, opposite a hilariously douchey Luke Wilson as Billy. The continued evolution of the Stab franchise remains one of the funnier self-referential aspects of the Scream sequels. Its self-parody also signals how screenwriter Kevin Williamson and director Wes Craven have turned their Scream 2 into a more comedic experience than the first, ever poking holes in genre conventions. For instance, new caller ID and *69 technology deflate the anonymous malicious caller, and Williamson comically addresses this in his script.

Work on Scream 2 was fast-tracked while the original was still in theaters, under the shooting title of Scream Again and later Scream Louder. Bob Weinstein, head of Miramax’s genre offshoot Dimension, told the press he hoped the sequel would debut with Scream still showing on screens. But that was not to be. Around the time the original was finally running out of steam at the multiplexes, in the summer of 1997, Scream 2 went before cameras and arrived in theaters before Christmas. Shooting with a $24 million budget, Craven had $10 million more to play with than its predecessor but decidedly less time to play. At least the casting process proved simple by comparison to the first, since Scream’s success prompted an influx of auditions from notable talent eager to appear in the sequel. Elsewhere, the production was subject to rampant speculation about the killer’s identity, and a new threat to Scream 2’s secrets arrived in the form of online sleuths—leading to a leak of 40 pages from an early script draft that didn’t amount to a significant problem given subsequent revisions. The filmmakers protected themselves further by keeping the last twenty pages of the script from the actors, so no one onscreen knew who the killer was or if their character was the culprit. Thus began a tradition of locking down Scream productions to keep storylines a tightly guarded secret.

Work on Scream 2 was fast-tracked while the original was still in theaters, under the shooting title of Scream Again and later Scream Louder. Bob Weinstein, head of Miramax’s genre offshoot Dimension, told the press he hoped the sequel would debut with Scream still showing on screens. But that was not to be. Around the time the original was finally running out of steam at the multiplexes, in the summer of 1997, Scream 2 went before cameras and arrived in theaters before Christmas. Shooting with a $24 million budget, Craven had $10 million more to play with than its predecessor but decidedly less time to play. At least the casting process proved simple by comparison to the first, since Scream’s success prompted an influx of auditions from notable talent eager to appear in the sequel. Elsewhere, the production was subject to rampant speculation about the killer’s identity, and a new threat to Scream 2’s secrets arrived in the form of online sleuths—leading to a leak of 40 pages from an early script draft that didn’t amount to a significant problem given subsequent revisions. The filmmakers protected themselves further by keeping the last twenty pages of the script from the actors, so no one onscreen knew who the killer was or if their character was the culprit. Thus began a tradition of locking down Scream productions to keep storylines a tightly guarded secret.

After the ground-breaking mixture of self-parodying laughs and slasher thrills purveyed in Scream, Craven and Williamson had expectations to meet. Could they extend the first movie’s level of rampant genre-aware in-jokes into the inevitable Scream 2 while maintaining the scares and not falling into the trap of a typical sequel? Since the original was so unique for transcending the slasher subgenre with its pop-culture references and discussions of horror movie formulas, Craven and Williamson had more pressure on them. They needed to appease horror fans and general audiences who had become interested due to Scream. Fittingly, their second go-round increases the amount of humorous film-related dialogue but spends less time trying to scare us, resulting in a predictable whodunit loaded with false alarms and red herrings. A couple of scary or tension-filled moments occur throughout, but Scream 2 feels more fun than its predecessor, particularly with the over-the-top Scooby-Doo climax. This is not to disparage the film but to note the evolution of the series into having a broader appeal than pure slasher horror.

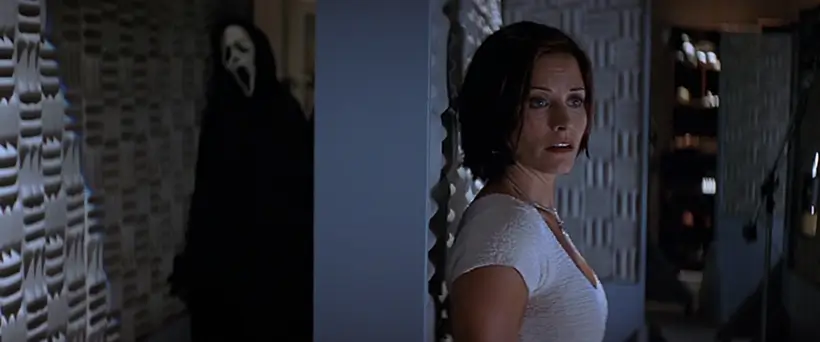

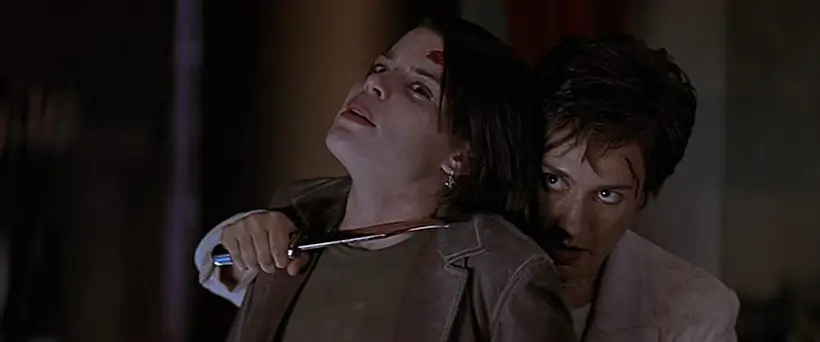

The sequel opens two years after the murders in Woodsboro, even though less than a year had passed since Scream was released. The murders during the Stab movie screening prompt the media to focus their attention on Sidney (Neve Campbell), who has since moved to Windsor College. Meddlesome reporter Gale joins the media frenzy on the campus, along with Cotton Weary (Liev Schreiber, in a considerably expanded role), the man wrongly imprisoned for the rape and murder of Sidney’s mother in Scream. Cotton looks to extend his fifteen minutes of fame by getting Sidney to agree to a Diane Sawyer interview. Meanwhile, Gale continues her flirtation with witless cop Dewey (David Arquette) as she investigates the recent deaths. And just as with the original, everyone—including Sidney’s new boyfriend (Jerry O’Connell)—is a suspect. Familiar faces make up the cast, and the killer could be among them: any number of sorority girls and frat bros; an intense drama teacher (David Warner); an ambitious local reporter (Laurie Metcalf); and fanatical film students (Timothy Olyphant, Joshua Jackson, Jamie Kennedy).

In typical sequel format, Scream 2 attempts to up the ante, as evident by the increased number of characters and a higher body count. And since most of the central cast makes it into 2000’s Scream 3, the sequel introduces several filler characters who quickly meet their demise. Sarah Michelle Gellar, fresh off her appearance in the Williamson-penned I Know What You Did Last Summer, which opened two months before Scream 2, gets stabbed and tossed out a window. Rebecca Gayheart (the former face of Noxema who would play a crazed killer the following year in Urban Legend) and Portia de Rossi (Arrested Development) play airheaded sorority sisters who disappear before the climax. Jackson makes a brief appearance, if only so Williamson could create synergy with his upcoming show Dawson’s Creek, on which Jackson starred. Metcalf, made famous on TV’s Roseanne, appears as a competing reporter and looks particularly crazy-eyed in later scenes. So many familiar faces keep the audience guessing which one could be the culprit, even if the answer—or half of it, anyway—proves easy enough to guess.

In typical sequel format, Scream 2 attempts to up the ante, as evident by the increased number of characters and a higher body count. And since most of the central cast makes it into 2000’s Scream 3, the sequel introduces several filler characters who quickly meet their demise. Sarah Michelle Gellar, fresh off her appearance in the Williamson-penned I Know What You Did Last Summer, which opened two months before Scream 2, gets stabbed and tossed out a window. Rebecca Gayheart (the former face of Noxema who would play a crazed killer the following year in Urban Legend) and Portia de Rossi (Arrested Development) play airheaded sorority sisters who disappear before the climax. Jackson makes a brief appearance, if only so Williamson could create synergy with his upcoming show Dawson’s Creek, on which Jackson starred. Metcalf, made famous on TV’s Roseanne, appears as a competing reporter and looks particularly crazy-eyed in later scenes. So many familiar faces keep the audience guessing which one could be the culprit, even if the answer—or half of it, anyway—proves easy enough to guess.

Jamie Kennedy’s Randy, the human survival guide to horror movies, appears again and tries desperately to graduate from a side character to a leading role by getting the girl. He fails, and according to his sequel rules, he must die. But before he does, he’s given winking scenes involving lengthy debates about the general deficiency of sequels next to their predecessors. His college film class discusses how sequels are hardly ever better than the original, citing examples from the superiority of Alien (1979) over Aliens (1985) to the classic appeal of The Terminator (1984) over Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991). Of course, you can guess the killer (or at least one of them) based on this debate, as he’s the only one defending the authority of sequels over the originals and the only one carrying a camera to record his crimes. To prove his point, he mentions The Godfather, Part II (1972) as a better film than its predecessor. Well, that’s debatable. What isn’t debatable is that, as the sole character to think sequels are better, he’s sure to end up being the killer. And if Scream 2’s raison d’être is to deliver a sequel that outclasses its predecessor, it cannot be called a success. Even so, it’s more intelligent than your average horror sequel.

Besides meta-ness about sequels, the film has more on its mind, including remarks about the horror genre’s treatment of race. The opening scene with Pinkett and Epps includes dialogue about how Black people rarely appear in horror movies, and further, they seldom survive. Pinkett’s character dismisses Stab for this reason, calling it “some dumb-ass white movie about some dumb-ass white girls getting their white asses cut the fuck up.” Minutes later, when their characters are dead, the audience is served with a hearty dose of satire that adds to the sequence’s greatness. Fortunately, Scream 2 features more performers of color than its predominantly all-white cast in the original, a point of contention for some detractors of the 1996 film. Besides Pinkett and Epps, the Black cast includes Elise Neal as Sidney’s best friend, Hallie, and Duane Martin as Gale’s newly assigned cameraman Joel, who has enough sense to leave when the killing starts. Hallie meets her demise in front of Sidney after a breathless sequence with the killer inside a crashed car. But after leaving, Joel returns in the final scene to help out Gale with a scoop, “like in the old days”—a line that makes little sense given their previous time together was a day ago. But it wouldn’t be until Scream 5 (2021) that the series would break its streak of predominantly white performers.

Baked into the proceedings is also a commentary on the impact of violent entertainment on culture, linking to Craven’s career-long obsession with the dynamic between reality and non-reality. The result is never good when people can’t distinguish between reality and movies. The opening sequence underscores this idea when Maureen dies on stage before a cheering audience slowly realizes her death is real. A similar scene on a stage occurs when Sidney rehearses a play about the Cassandra myth. Its director has rather inconsiderately put the students playing the Greek chorus in dark robes with masks that recall Ghostface. As they rehearse, Sidney, as Cassandra, is haunted by masked figures. But then the killer hides among the chorus and torments Sidney—a case of art imitating life imitating art. As it turns out, that becomes an entrenched theme of Scream 2, from the horror movie Stab, which is based on “real-life” events, to the killer initially targeting students with names similar to victims in the first film. Moreover, when Sidney confronts the killer in the climax, it’s back on the theater stage. The killer’s plan to get away with murder by blaming violent movies (“Hell, the Christian Coalition will pay my legal fees!”) cannot help but feel like Williamson and Craven commenting on the absurd reactions of conservative groups who blame the movies whenever some disturbed individual goes on a killing spree.

Baked into the proceedings is also a commentary on the impact of violent entertainment on culture, linking to Craven’s career-long obsession with the dynamic between reality and non-reality. The result is never good when people can’t distinguish between reality and movies. The opening sequence underscores this idea when Maureen dies on stage before a cheering audience slowly realizes her death is real. A similar scene on a stage occurs when Sidney rehearses a play about the Cassandra myth. Its director has rather inconsiderately put the students playing the Greek chorus in dark robes with masks that recall Ghostface. As they rehearse, Sidney, as Cassandra, is haunted by masked figures. But then the killer hides among the chorus and torments Sidney—a case of art imitating life imitating art. As it turns out, that becomes an entrenched theme of Scream 2, from the horror movie Stab, which is based on “real-life” events, to the killer initially targeting students with names similar to victims in the first film. Moreover, when Sidney confronts the killer in the climax, it’s back on the theater stage. The killer’s plan to get away with murder by blaming violent movies (“Hell, the Christian Coalition will pay my legal fees!”) cannot help but feel like Williamson and Craven commenting on the absurd reactions of conservative groups who blame the movies whenever some disturbed individual goes on a killing spree.

Scream had earned Craven some of the best reviews of his career and was his biggest box-office success at that time. Similarly, Scream 2 reached the $100 million mark by January’s end, four months quicker than the original. Though, it didn’t last in theaters as long as its predecessor; they both made about the same amount in worldwide receipts, within less than a million dollars of each other. The reviews were likewise positive, with almost universal praise from critics such as Janet Maslin in The New York Times, who remarked that Craven, having long desired to expand his genre horizons, had finally escaped horror since the sequel barely qualified given its wealth of “tongue-in-cheek trickery.” However, in an ironic and tragic case of life imitating art, a copycat killing brought negative press on Scream 2. In January 1998, California resident Gina Castillo was murdered by her 16-year-old son and his 14-year-old cousin. The killers later claimed they based the killing on the Scream movies and even planned to purchase similar costumes as Ghostface. Craven stayed away from the story and refused to indulge any remarks about how this incident related to his movies.

Although Scream 2 follows its predecessor’s template as a self-reflexive slasher blended with a comic whodunit, Craven and Williamson’s themes about race in the horror genre and trends in horror sequels suggest a movie with more than mindless thrills in store. But it becomes superior when considering its many-layered ideas about the relationship between reality and mimesis, and whether violent media affects its viewers. Of course, Craven and Williamson never make a case for censorship, but the series’ continued exploration of these ideas uses a curious device—crazed killers who adhere to slasher movie blueprints to carry out their murderous agendas. While this could be seen as an indictment of how scary movies influence viewers, it’s more aptly a condemnation of those disturbed individuals who cannot distinguish between reality and fiction. But these are not new ideas—Scream explored them as well. And even though the sequel doesn’t break the mold established by the original, it manages to be another playful and wildly entertaining ride. In addition, it rises above other slasher sequels by resolving to be more than just a rehash. Regardless of the short turnaround, Craven and Williamson do more than crank out a repeat, leaving Scream 2 to hold up to scrutiny as one of the horror genre’s best sequels.

(Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon and published on March 1, 2023.)

Bibliography:

Maroney, Padriac. It All Began with a Scream. BearManor Media, 2021.

Robb, Brian J. Screams and Nightmares: The Films of Wes Craven. Polaris Publishing, Inc., 2022.

Wooley, John. Wes Craven: The Man and His Nightmares. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2011.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review