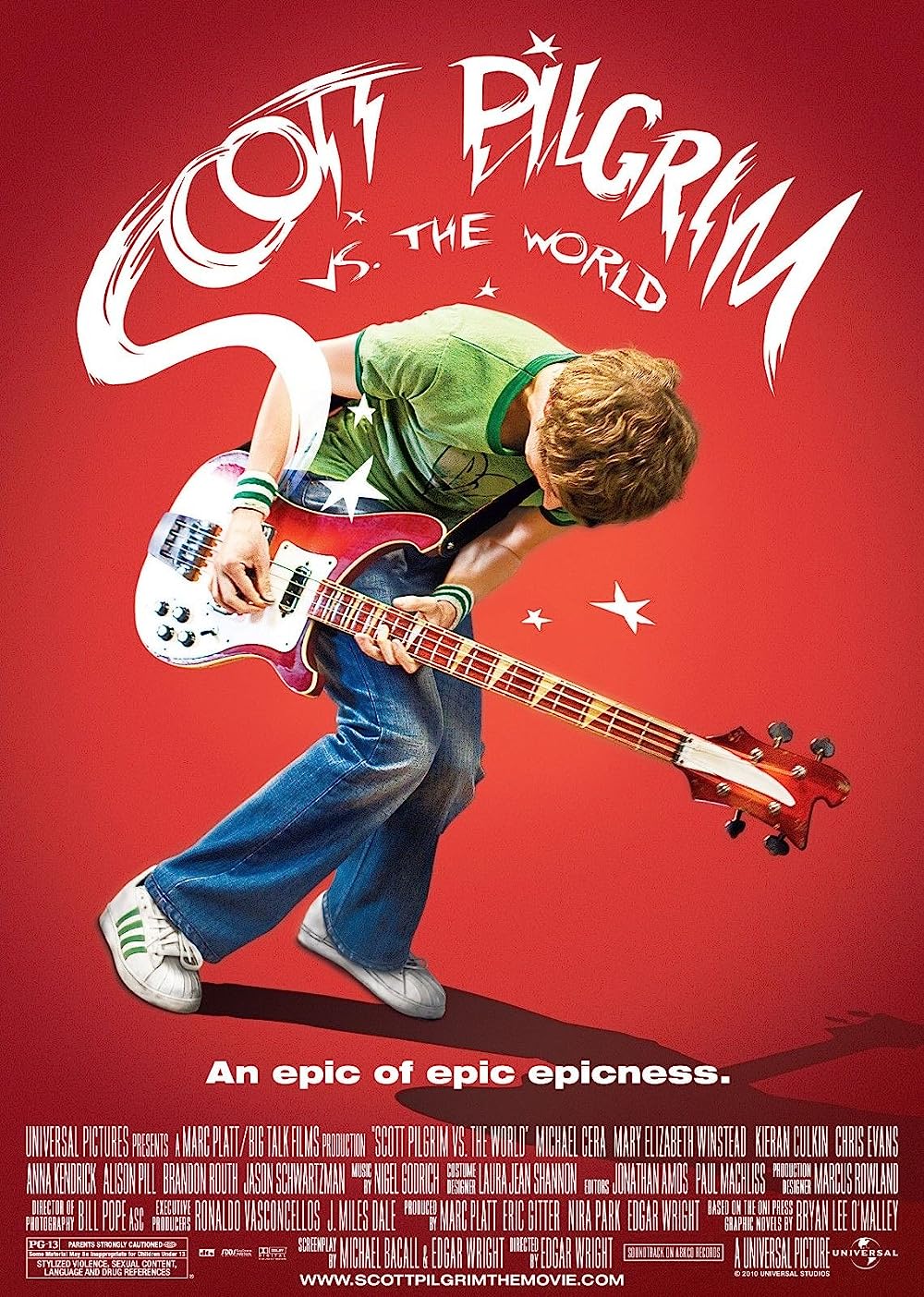

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

By Brian Eggert |

In a glorious piece of synesthesia, director Edgar Wright brings on a fully uniform assault of the senses with Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, based on the graphic novel by Bryan Lee O’Malley. Wright takes a unique medium, namely the videogame world, and perfectly translates it to cinema, constructing what will be the example for future videogame-to-film adaptations, in that, with the right approach, the much-maligned genre can work. How ironic that the film’s source isn’t even a videogame; and yet, the film plays by videogame rules, but at the same time splices a romantic comedy with a typical videogame-level structure. While the story is clever and often hilarious, the way Wright brings together his unbelievable production—from the story to his meticulously composed and layered presentation—is what makes the film so exciting and even important.

The impeccably stylized approach by Wright and his editors Jonathan Amos and Paul Machliss alone demands attention. They create zooming transitions and fight scenes arranged at a breakneck pace, which our bodies follow as if the film itself were literally transporting us from location to location within the story. Visual cues appear onscreen, such as a yellow 16-bit “pee meter” that goes down as one character urinates. When the protagonist, Scott Pilgrim (Michael Cera), awakens one morning and steps from a dark room into a bright bathroom, white light beams and he screams “Ahhhhh!”—the letters appearing around him like a comic book. Indeed, the universe of Wright’s film is not reality, but a place ruled by the logic of video games and comic books, and indie rock music. And your understanding of those worlds is crucial to your enjoyment of the film.

When the film opens, Scott Pilgrim seems like a normal young guy in his early twenties. He’s still brokenhearted over an ex-girlfriend that dumped him long ago, so he’s dating a sympathetic 17-year-old Chinese high school girl named Knives Chau (Ellen Wong) to make himself feel better. They don’t kiss or touch, they barely even hold hands. Scott just wants the company of the cute girl to boost him, until he dreams about Ramona Flowers (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) roller-skating through his head, and then sees her the next day in the flesh, Brazil style. She must be ‘the one’ and he must pursue her. When he does, he discovers that in order to date her, Scott is obligated to defeat Romona’s Seven Evil Exes, and they appear for elaborate battles inspired by fighting games like Mortal Kombat and Tekken. But there’s more substance and emotional maturity to the plot than mere fights to win the girl. Scott’s battles become about earning self-respect, so his liaison with Romona may move beyond puppy-love infatuation and burgeon into a full-fledged relationship.

The fights themselves are truly remarkable displays of Wright’s talent, ones that are easier to understand if you’re familiar with videogame culture, but remain clear regardless of your experience. In other words, anyone can grasp the gist of the film, but how much depends on how much time you’ve spent playing Nintendo, watching cult movies, and reading comic books. Scott fights Romona’s exes in elaborate kung-fu escapades (which Cera somehow makes look believable) and when he’s finished, a final blow busts them into quarters. Each bout is preceded by a “Fight!” marker appearing in pixilated digital lettering, while power-up signs flash across the screen at decisive moments. It’s all moving at a whirlwind pace, zipping by with the speed of a, well, videogame that it must be watched twice, or three times, to catch all the references.

The impressive supporting cast of Scott’s friends (and enemies) stand in awe of these fights as well. Anna Kendrick plays Scott’s wise sister; Kieran Culkin is Scott’s wonderfully sarcastic-yet-supportive gay roommate; Alison Pill, Mark Webber, and Johnny Simmons play the other members of Scott’s struggling band, Sex Bob-Omb. These characters make Scott’s quest for love more than just a quest for love, complicating his life, and forcing him to question his decisions and behavior at every turn. They each have a real presence throughout the film, and they each have more than one layer to them, in turn, deepening the emotional questions at the center of Scott’s ongoing conflict. Meanwhile, the evil exes each make their mark, such as Chris Evans’ hilarious macho skater movie star Lucas Lee, or Brandon Routh’s musician with fantastical “vegan powers”. Romona’s exes were assembled by hysterically slimy record executive Gideon (Jason Schwartzman), the final end-game boss who Scott must defeat to win this game of love.

Throughout the inspired battles and unending humor, the film has only two limitations that hinder its potential enjoyment. Audiences unable to swallow Michael Cera’s onscreen appearance are not to be blamed, as the actor has played virtually the same role since his beginnings in TV’s Arrested Development, then moving on through Superbad, Juno, Youth in Revolt, and now this. It’s easy to grow tired of his typecast appearance, but if you never see another movie with the actor, see Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. This is the best thing he’s ever done. The second limitation involves the film’s potential for mass appeal. Granted, Ma and Pa Kettle probably won’t “get” the layered humor or visual, videogame-centric gags working overtime throughout the production. Certain audiences just won’t be attuned to every little detail that pops up onscreen (you could probably spend hours upon hours trying to identify where all the references come from); those unfamiliar with the film’s home base culture will simply be lost. After all, the film’s characters play by rules established in the arcade and inside comic books, not by any logical or scientific constraints. Viewers untried in those realms will have no idea why this or that is happening.

But for his key demographic—the same audience that “got” all of the jokes in the television show Spaced, or his films Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz—Wright has constructed an extraordinary piece of entertainment. It’s unlike anything you’ve seen before, and that’s a statement not made often with today’s cinema. Wright proves himself a revolutionary filmmaker and an adroit storyteller, never reducing the main characters of Scott and Romona to one-dimensional types, though they could have easily been made that way. The film assembles no end of visual and auditory in-jokes, references, and stylistic flourishes for an audience to discover, yet the colorful and expressive presentation amazingly never takes precedence over the emotional core of the story. For such an audacious display of cinematic bravado to still affect its audience in a meaningful way is an achievement to be sure, and the way it all comes together is Wright’s most impressive feat in an already incredible film.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review