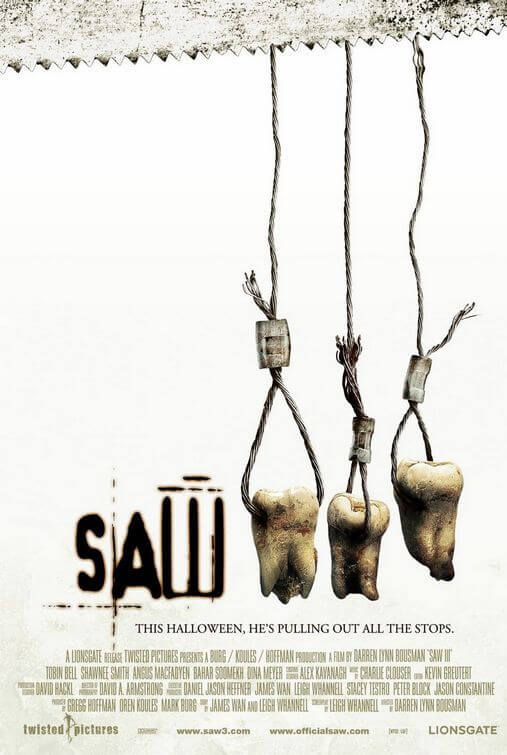

Saw III

By Brian Eggert |

Following the Jigsaw killer’s philosophy of revelation through pain, the end of Saw II reveals that the Jigsaw Killer’s first survivor, Amanda (Shawnee Smith), has been working with him as an accomplice. Saw III explores that idea further, with Jigsaw (Tobin Bell) nudging Amanda to create her own murderous, pseudo-lecture devices. The problem is, Amanda doesn’t give her subjects the same potential to escape that Jigsaw normally grants. The movie begins with Detective Kerry (Dina Meyer), a background character in previous entries, caught by Amanda and forced to endure an even more maniacal interpretation of Jigsaw’s tortures. Det. Kerry’s ribs are locked into hooks and will be pulled apart unless she can reach inside a jar of acid for the key. Worse, she just came from a copycat Jigsaw murder scene where the victim was never given a chance for redemption. She realizes she’s doomed when Amanda reveals herself as her captor.

Enter Dr. Lynn Denlon (Bahar Soomekh), who is kidnapped and brought by Amanda to Jigsaw’s seedy industrial lair. Her assignment seems simple enough: keep Jigsaw, who is still dying from his brain tumor, alive for a few hours to watch his latest set of games play out. Her challenge becomes increasingly difficult (and laughable) when she has to conduct brain surgery with little-to-no medical equipment. Jigsaw’s disease humanizes his character (or so it seems), making Amanda the villain. He’s even called by his first name, John, for most of the movie. John/Jigsaw remains immobile and sickly in bed, with all sorts of medical contraptions attached to him. Dr. Denlon sees his file and knows his case is hopeless, which makes me wonder, what beef does John have against his doctors? It’s not their fault he has a tumor. Maybe he should spend more time wrapping up his life in his last days and less time torturing his former physicians.

Anyway, Jigsaw’s latest game also involves Jeff (Angus MacFadyen), a father whose son tragically died at the hands of a reckless driver. Now Jeff spends his time wallowing and making his one remaining child feel neglected. And so Jigsaw allows Jeff to cleanse himself of hatred by placing him in the position of mercy-giver over those few (a witness, a judge, his son’s killer) whom Jeff blames for the tragedy. Jeff can either watch them die in one of Jigsaw’s devices or forgive them and help them escape.

Jigsaw’s “lesson” is one seldom learned. Besides Amanda, the only other survivor is Dr. Gordon from the first Saw. Did we ever find out what happened to him? And what about Det. Matthews from Saw II? Did he die, or what? Can anyone explain these uncountable open ends? How can Jigsaw possibly think he or his undertaking has achieved anything with such a low success rate? He would do better by looking at the numbers, realizing he’s doing more harm than good, and trying a new approach. I wish these films would do the same. Jigsaw’s twisted logic asks people to transfer their emotional problems into physical ones, but why give them limited time to work through them? In some cases, they’re given a mere sixty seconds to free themselves from their physical and psychological hangups. Perhaps Jigsaw should crunch some numbers and reevaluate his unrealistic requirements.

Saw III relies on a twisting, drained formula where torture subjects are once again confronted with impossibly goriffic situations. This one’s ending is particularly dismal. Everyone, and I mean everyone, dies. So what’s the point? Jigsaw attains the level of Michael Myers or Jason Voorhees, meaning his movie appearances get stupider and gorier with every new entry. Whereas most sequels decline financially with additional sequels, spelling their eventual demise, this franchise has remained uncannily profitable. Each entry is made for a relatively cheap $4 or $5 million and then returns more than $50 million in receipts and DVD sales. Perhaps when Saw XIII is released, we’ll begin to see diminishing returns.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review