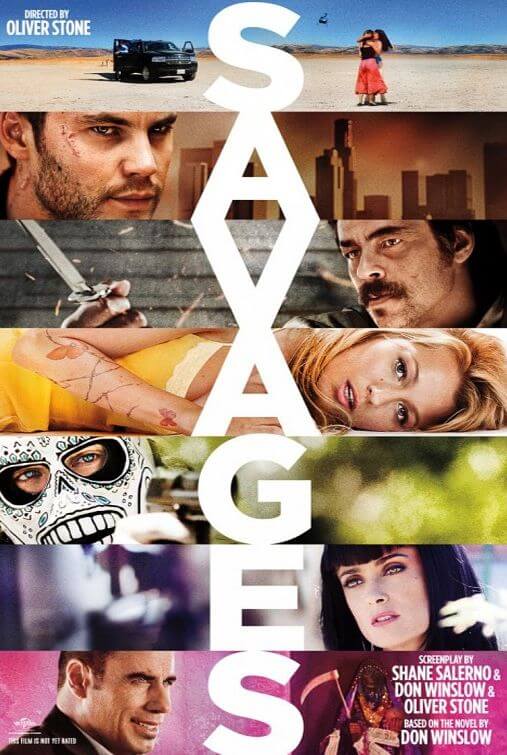

Savages

By Brian Eggert |

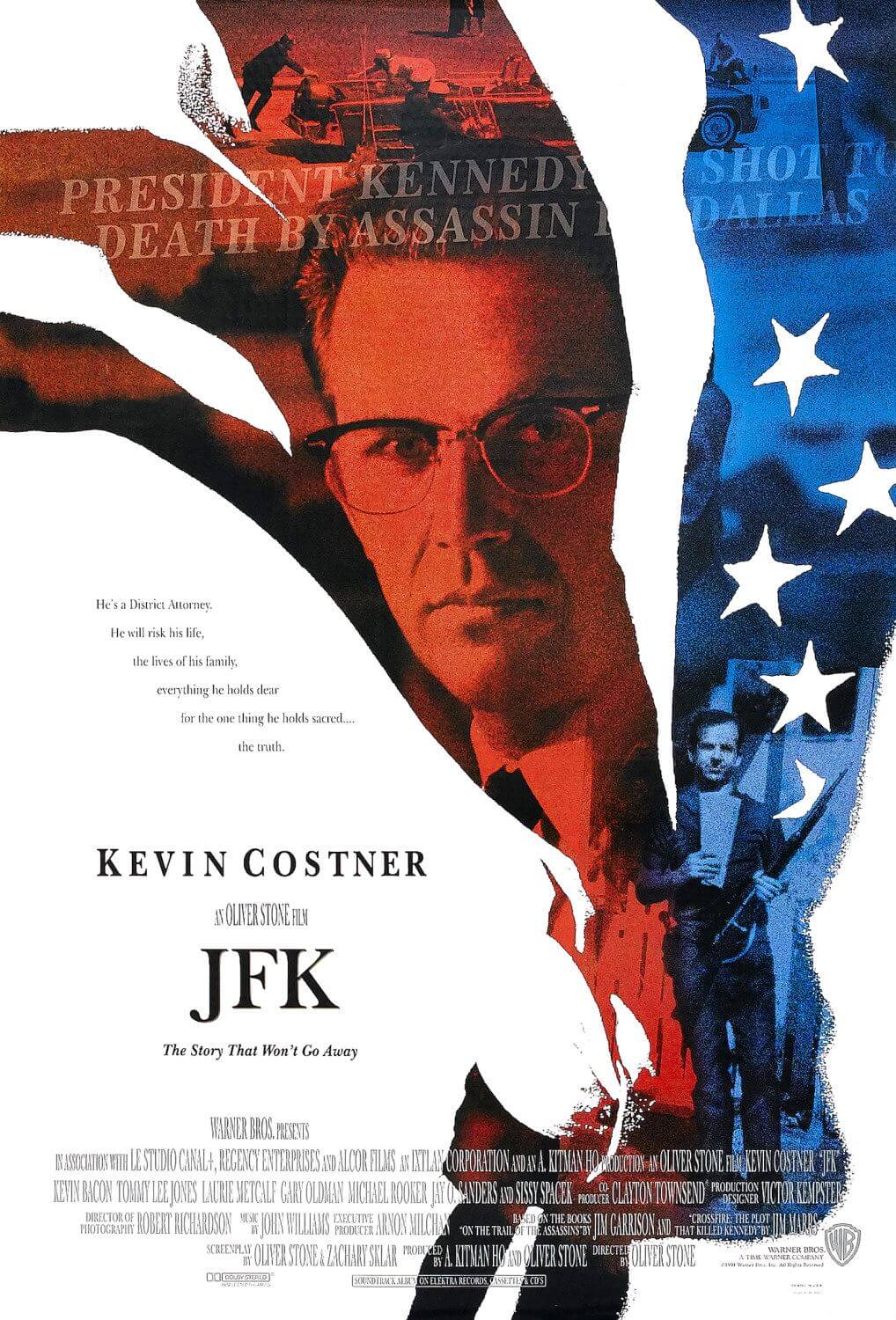

Oliver Stone’s Savages marks a minor return to form for the filmmaker whose height was twenty years ago with Natural Born Killers and JFK, and whose own savage instincts have since tapered with harmless, unremarkable fare like World Trade Center and Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps. Based on Don Winslow’s novel, the picture concerns an ugly war between two Californian pot growers and the Mexican cartel out of Baja. Cooked under an omnipresent harsh sun, relations between the two parties escalate into bloody violence, and the scenario provides a ripe piece of pulp fiction wherein Stone’s cast brings to life colorful characters in a number of enjoyable performances. But as these various criminals try to out-maneuver one another, the plot’s twists and turns give way to a curious finale. With a somewhat noirish opening, a thrilling center, and a post-modern ending (the latter of which could potentially make or break the experience for moviegoers), Stone’s revitalization of his primal side is an uneven if admirable effort.

The story is narrated by Ophelia (Blake Lively), who warns us early on, “Just because I’m telling you this story doesn’t mean I’m alive at the end of it.” Either that’s a promise, or merely an annoying deception to instill doubt in the viewer. You decide. To distance herself from the Hamlet character after which she was named, she goes by just “O” instead. But this character has a secret affinity for Shakespearian tragedy, as we learn late in the film. O is the lynchpin in an ongoing threesome with two odd couple drug dealers, bromance buddies Ben (Aaron Johnson) and Chon (Taylor Kitsch). The former is a pacifist botanist and the latter an Iraq veteran killing machine, and their business relies on distributing a top-of-the-line product with limited need for violence. Given their marijuana’s high THC level, the Baja Cartel, headed by Elena (Salma Hayek), wants a piece of their action and an insight into their science. But both men want out of their trade, and the cartel’s three-year partnership proposal sounds more like a threat than a business proposition.

When Ben and Chon refuse the cartel’s offer and make plans to leave the country to avoid any unpleasant consequences, Elena’s psychopathic right-hand Lado (Benicio Del Toro) kidnaps O to coerce her two lovers to comply. Out of fanatic devotion to O, Ben and Chon agree to Elena’s terms, but she refuses to release her hostage until the two men can be trusted. In turn, they seek retribution; they gather intel from corrupt DEA agent Dennis (John Travolta), who supplies them with details on Elena’s network, and they launch an attack. Meanwhile, as Lado carries out Elena’s orders, he’s also setting himself up to take over the cartel. Each character has his or her own motivations. None of them are particularly good people, all of them are criminals, and at least one or two are downright evil. Mix them up, and this interplay of fascinating and volatile personalities brings about a spree of violence, sex, and drugs. On the whole, it’s incredibly entertaining.

These character dynamics make for compelling acting, particularly from Hayek, who, under a Cleopatra wig and in full authoritarian mode, gives her cartel queen a surprisingly human side that develops in her talks with O. Del Toro is equally great, but his performance is of another kind entirely; unsympathetic and grotesquely cruel, Lado is a wonderfully evil character played to perfection by this actor. Travolta is amusing and sleazy as the corrupt cop playing both sides for his benefit. Strangely enough, the trio of protagonists proves less interesting, perhaps in part because their threesome is never quite believable. Ben and Chon love each other in a bromance way, whereas O’s inclusion feels secondary, as though she’s the excuse to keep these two men together. Her (incessant) narration tries to explain the romantic logic of their three-way relationship, but it never makes sense in the same intuitive way Woody Allen made a similar situation believable in Vicky Cristina Barcelona.

Along with Stone’s lively direction—he uses a range of formal techniques, from black-and-white photography to the occasional overexposure, but nothing as dynamic as his flourishes in Natural Born Killers—comes a narrative structure that attempts to play with conventions, and thus its audience. O hints early on how she could be an unreliable narrator, and her constant exposition remains a frustratingly dull source of background information we have no choice but to trust. But the kicker comes when, reminiscent of Michael Haneke’s Funny Games, the film provides two endings. One ending is almost Shakespearian, a decidedly romantic view and tragic finish where these characters meet a fate similar to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid; the other ending feels absurd and perhaps too convenient, but romantic in another way. One is intentionally derivative; the other is contrived. Neither is very satisfying, and the film’s way of presenting two possible endings feels unjustified in an otherwise traditionally composed crime thriller.

Because of this out-of-left-field irregularity in the storytelling, Savages leaves its audience feeling robbed of genuine resolution to the fascinating yarn that preceded it. We’re left with the tale’s half-hearted and underdeveloped theme about what the relative term “savage” means. To answer this question, O—who’s none too cultured—offers a dictionary definition of the word as though she’s writing a grammar school essay. Her explanation is neither substantial nor perceptive, nor even one that lends meaning to the film’s events; it’s a bogus way of trying to rationalize the film’s sheer amoral pandemonium. Since, in the past, Stone’s crime pictures like Natural Born Killers and U-Turn embraced the meaningless of chaos, one can’t help but see this film as a failed attempt to reach their level of excellence. And while the juicy performances and exciting meat of Savages are vicious fun, it’s a film whose feeble conceit undoes the pleasures of its base appeal.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review