Reader's Choice

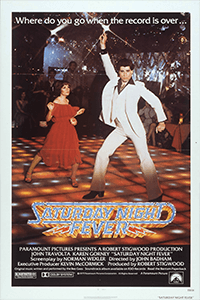

Saturday Night Fever

By Brian Eggert |

The disco club in Saturday Night Fever supplies an irresistible metaphor for the film, which remains lauded for its dreamy dance sequences and memorable soundtrack. At the Brooklyn club 2001 Odyssey, primary-colored lights, reflective walls, flickering squares on the illuminated dance floor, and a glimmering disco ball create an atmosphere of sparkle. But look beyond the fog machine and cigarette smoke haze, and you see the cheapness of it all: the tacky tablecloths, the almost palpable stale stink in the air, the plastic décor. In the club’s bar, a sole stripper dances on a small stage rather sadly, mostly ignored. And while the music usually has a good beat and some catchy melodies, the dull lyrics hint at disco’s superficiality, which was proclaimed dead by 1980. Although the film deploys a compelling theme about the importance of personal expression in pursuing something you love, its protagonist, John Travola’s Tony Manero, goes from challenging the audience’s allegiance to becoming downright despicable by the conclusion, to the extent that one might stop caring whether he gets to pursue his dreams or not. But even today, Travolta’s signature dancing and the Bee Gee’s soundtrack epitomized the public’s general impression of the 1977 film, leaving its seedier elements either forgotten, suppressed, or conveniently ignored.

Saturday Night Fever was designed to capitalize on the box-office success of John G. Avildsen’s Rocky (1976) and its crowd-pleasing interest in relatable heroes emerging from their working-class misery. Mega-producer Robert Stigwood even hired Avildsen to direct the adaptation of Nik Cohn’s largely fictionalized New York magazine article, “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night” before replacing him with John Badham. With its morally ambiguous screenplay by Norman Wexler—who wrote Avildsen’s Joe (1970) and Sidney Lumet’s Serpico (1973)—and the modest star power of Travolta, who had earned a name for himself on TV’s Welcome Back, Kotter (1975-1979), the film was likely to be a hit. Stigwood, also a band manager for Cream, arranged for his falsetto-voiced disco troupe, the Bee Gees, to dominate the soundtrack. Primarily popular in Australia and the UK at the time, the Bee Gees’ music was added in post-production by Stigwood, launching them into international superstardom after the film’s release. The soundtrack earned the Bee Gees a Grammy for Album of the Year and became one of the all-time best-selling records in music history, epitomizing the disco movement with songs such as “Night Fever” and “Stayin’ Alive.” All of the flash and sex appeal that Stigwood injects into the production, however, threatens to distract from the material’s substance.

From the opening credits, where Travolta’s 19-year-old Tony walks down the scuzzy streets of Brooklyn’s Bay Ridge neighborhood, he oozes confidence and sex appeal, armed with a black leather jacket, red shirt, platform shoes, and jive in his step. Tony pesters women and window shops, his machismo disguising his naive and frustrated worldview, his sense of feeling trapped and unappreciated. Later in the film, he remarks that he’s only ever received two compliments: about his dancing and a pathetic raise at his thankless hardware store job that, unless he escapes, will be his fate. At home, Tony’s stereotypically volatile Italian family consists of an unemployed construction worker father, Frank (Val Bisoglio), and a hyper-religious mother, Flo (Julie Bovasso), who berate Tony at every opportunity. Tony also has a little-seen younger sister and an absent older brother in the priesthood, Frank, Jr. (Martin Shakar), whom his parents idolize and use to demonize Tony by comparison. Treated like a child at home, Tony has childish heroes and desires; his bedroom walls are covered with posters of men he yearns to be (Bruce Lee, Al Pacino, and Rocky Balboa) and impossible women he dreams about (Farrah Fawcett, Linda Carter’s Wonder Woman). There, he prepares himself for the world in front of the mirror, fussing over his hair and adjusting his package as he admires his lean body.

When the weekend comes, Tony plans to spend the week’s modest earnings at 2001 Odyssey with the boys—Tony’s mostly detestable band of moron friends who harass a gay couple, spout racial epithets, and treat women as undeserving of friendship. They pound their chests, look for excuses to fight, and use the back seat of a car, owned by the weakest in their clan, Bobby (Barry Miller), for alternating sexual encounters with random women, often while the others watch. In their company, one cannot help but think of Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973), featuring a similar contingent of lowlifes; however, at least Harvey Keitel’s protagonist maintained a pressing moral compass rooted in Catholic guilt, creating an emotional conflict. Tony’s worldview is utterly selfish, viewing everyone outside his home, especially women, as unworthy of his time unless it serves him. Tony’s sole reprieve from these thankless surroundings occurs on the dance floor, where he’s in his element—admired by all for his practiced moves, especially women who wonder whether Tony can move that well in bed.

When the weekend comes, Tony plans to spend the week’s modest earnings at 2001 Odyssey with the boys—Tony’s mostly detestable band of moron friends who harass a gay couple, spout racial epithets, and treat women as undeserving of friendship. They pound their chests, look for excuses to fight, and use the back seat of a car, owned by the weakest in their clan, Bobby (Barry Miller), for alternating sexual encounters with random women, often while the others watch. In their company, one cannot help but think of Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973), featuring a similar contingent of lowlifes; however, at least Harvey Keitel’s protagonist maintained a pressing moral compass rooted in Catholic guilt, creating an emotional conflict. Tony’s worldview is utterly selfish, viewing everyone outside his home, especially women, as unworthy of his time unless it serves him. Tony’s sole reprieve from these thankless surroundings occurs on the dance floor, where he’s in his element—admired by all for his practiced moves, especially women who wonder whether Tony can move that well in bed.

Saturday Night Fever follows two story threads concerning Tony’s relationship with women and his desire to escape his current life. As for women, he summarizes his views when he asks, “Are you a nice girl or a cunt?” Translation: “Will you sleep with me or not?” Then again, if a woman is too easy, she becomes either a “bitch” or a “cunt,” so women can’t win with him. Nevertheless, he orbits two prospects, both dancing partners: Annette (Donna Pescow), a girl from the neighborhood who loves him but wouldn’t sleep with him initially, and Stephanie (Karen Lynn Gorney), a shameless namedropper who exposes Tony to a world outside of Brooklyn, namely Manhattan, where he can pursue his dreams. If Tony could only do something with his dancing, he could get out of Bay Ridge. Dancing is the one thing he loves; it makes him feel high. “I would like to get that high someplace else in my life,” Tony says. But as Stephanie shrewdly observes about his current situation, “You’re nowhere on your way to no place.” At this, Tony’s desire to flee the frustrating mediocrity of his blue-collar existence for a more romantic, middle-class life in a cosmopolitan city brings him to tears, looking at the bridge in the distance that could be his literal path out of Brooklyn. It’s a fine piece of acting, but it establishes a sensitivity that the writing often betrays or contradicts.

Modeled after Rocky except less obvious, Saturday Night Fever builds toward the similarly complex outcome of a competition. Just as Rocky technically loses but actually achieves a victory by presenting a challenge to Apollo Creed, Tony’s eventual win of a disco dance competition isn’t an unqualified triumph. For starters, Tony has already danced better in the film than he does in the competition. After ditching Annette, his original (and superior) dance partner, for Stephanie, Tony and Stephanie practice. All the while, he pines after her, unable and unwilling to keep their friendship platonic. But their bond is thin, driven by Tony’s relentless pursuit of Stephanie, who can provide Tony with what he wants—escape. Their performances in the studio and the competition, set to the Bee Gee’s mild-tempoed “More Than a Woman,” are neither impressive nor very entertaining. Tony’s dances with Annette and, in particular, his solo performances are far more skilled. But he and Stephanie seem to be falling for each other during the dance, which ends with a kiss. Even so, the Puerto Rican couple who performs after them are more skilled, and Tony knows it. At the announcement that Tony and Stephanie have won the top prize, he decries his friends and the judges’ prejudiced refusal to acknowledge that the Puerto Rican couple danced better. So he gives the other couple the prize money and trophy and pulls Stephanie out of the club.

Much of what happens after the competition is what derails Saturday Night Fever. Tony attempts to force himself on Stephanie in the back seat of Bobby’s car, and when she fights her way out of it, he attempts to reclaim Annette, who has since taken speed and directed her affections at one of Tony’s friends. While the group drives around the city, Tony stews about the competition and Stephanie’s rejection, saying nothing as his friends rape a pleading Annette in the back seat. Soon, they stop at the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge—their favorite spot to perform daredevil climbing stunts and shout “Fuck you!” at their oppressive world. Tony turns to the rattled Annette accusingly and asks, “Proud of yourself now?” before deciding she’s a “cunt” for getting raped. By this point, Tony’s otherwise relatable sense of alienation and suffocation has twisted him into a monster, though the audience is expected to empathize with him still. Alas, the film never deals with Annette’s rape because it’s too eager to get to Bobby’s death, who, depressed that a girl he got pregnant refuses to get an abortion, self-destructively walks on the bridge and falls. Annette shields herself from the sight in one of her rapist’s arms, ignoring that she was sexually assaulted twice in the back seat moments before. In his Great Movies essay, Roger Ebert rationalized the scene: “Of course, at that time, in that milieu, perhaps it wasn’t considered rape, but only an energetic form of courtship.” Annette’s cries from the back seat suggest otherwise.

Much of what happens after the competition is what derails Saturday Night Fever. Tony attempts to force himself on Stephanie in the back seat of Bobby’s car, and when she fights her way out of it, he attempts to reclaim Annette, who has since taken speed and directed her affections at one of Tony’s friends. While the group drives around the city, Tony stews about the competition and Stephanie’s rejection, saying nothing as his friends rape a pleading Annette in the back seat. Soon, they stop at the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge—their favorite spot to perform daredevil climbing stunts and shout “Fuck you!” at their oppressive world. Tony turns to the rattled Annette accusingly and asks, “Proud of yourself now?” before deciding she’s a “cunt” for getting raped. By this point, Tony’s otherwise relatable sense of alienation and suffocation has twisted him into a monster, though the audience is expected to empathize with him still. Alas, the film never deals with Annette’s rape because it’s too eager to get to Bobby’s death, who, depressed that a girl he got pregnant refuses to get an abortion, self-destructively walks on the bridge and falls. Annette shields herself from the sight in one of her rapist’s arms, ignoring that she was sexually assaulted twice in the back seat moments before. In his Great Movies essay, Roger Ebert rationalized the scene: “Of course, at that time, in that milieu, perhaps it wasn’t considered rape, but only an energetic form of courtship.” Annette’s cries from the back seat suggest otherwise.

I suppose we’re meant to understand Tony’s sense of feeling trapped and unable to do what he’s passionate about because of his social class. Such a feeling of inadequacy and confinement is a relatable notion, to be sure. So few of us make a living doing what we love; we have day jobs, and like Tony, we pour ourselves into our hobbies for fulfillment. Despite our dissatisfaction, the hope is that we make the best of it. And in narrative terms, Saturday Night Fever attempts to redeem the complex Tony because he’s more sensitive than his compatriots; he cries in Stephanie’s presence, recognizes his friends’ bigoted hypocrisy at the dance competition, and Bobby’s death reminds him of the shortness of life. The film’s final scene conveniently finds Tony at Stephanie’s apartment in Manhattan, the two reconciling over a hug and agreeing to be just friends. Ebert argues that Tony has “a more enlightened view of women” by the end, “and so the themes have been resolved.” But I don’t believe the film adequately confronts Tony’s behavior, male rage, flagrant sexism, and insecurities. It’s too eager to roll the credits, get the Bee Gee’s “How Deep is Your Love” in our ears, and let him off the hook, suggesting his inner conflicts have conveniently resolved themselves after a pensive subway ride montage following Bobby’s death. All of this is further negated by Staying Alive (1983), the sequel that reveals Tony’s behavior hasn’t changed much (but the less said about the sequel, the better).

Today, many view Saturday Night Fever through rose-colored glasses, maybe because they saw the film in a highly edited PG-rated cut or edited for television. Upon the release of the original cut, Paramount realized they had a box-office smash, owing mainly to the crazed youth fandom of John Travolta and the Bee Gees. But the language, nudity, and multiple rape scenes prevented the teen audience from catching their favorite star dancing to their favorite songs. With the original cut released in December 1977, it’s impressive that the film remained in the zeitgeist for an entire year until the PG version arrived in theaters in 1979. The re-release poster declared, “IT IS NOW RATED PG” and added, “Because we want everyone to see John Travolta’s performance… Because we want everyone to hear the #1 group in the country, the Bee Gees… Because we want everyone to catch ‘Saturday Night Fever.’” In the subsequent years, most networks that acquired the television rights purchased the edited version, whereas HBO played the edited cut during the day and the uncensored cut at night. The PG version may have been compromised, but it gave Tony a more convincing and commercial-friendly redemption arc. Indeed, there’s every likelihood that someone could go through this life without knowing Tony Manero is an attempted rapist and complicit in Annette’s victimization in the back seat of Bobby’s car.

The film is also a time capsule, containing a glimpse at a dead music genre and a nightclub scene that lasted a few years in the mainstream consciousness. But few critics from the 1970s addressed how its predominantly white heterosexual characters occupy disco clubs that, in reality, supplied inclusive environments, predominantly for marginalized African American, Puerto Rican, and LGBTQ+ communities. Ironically, as Stanford dance historian Richard Powers notes, it was Saturday Night Fever that turned this “simmering subculture into a mainstream fad” and introduced many white communities to the disco scene. With dance numbers by choreographer Lester Wilson, a man of color, and performed by an Italian whose ethnic group is white, the film’s appropriation extends to Tony, who remarks, “I look as sharp as I can without being [Black]” (he uses the N-word)—a line that underscores not only Tony’s racist worldview but his commandeering of Black style.

The film is also a time capsule, containing a glimpse at a dead music genre and a nightclub scene that lasted a few years in the mainstream consciousness. But few critics from the 1970s addressed how its predominantly white heterosexual characters occupy disco clubs that, in reality, supplied inclusive environments, predominantly for marginalized African American, Puerto Rican, and LGBTQ+ communities. Ironically, as Stanford dance historian Richard Powers notes, it was Saturday Night Fever that turned this “simmering subculture into a mainstream fad” and introduced many white communities to the disco scene. With dance numbers by choreographer Lester Wilson, a man of color, and performed by an Italian whose ethnic group is white, the film’s appropriation extends to Tony, who remarks, “I look as sharp as I can without being [Black]” (he uses the N-word)—a line that underscores not only Tony’s racist worldview but his commandeering of Black style.

Of course, no film should be required to make its protagonist likable or morally upright, but Tony passes a point of no return after the dance competition for this critic. Even beyond the rape context, Saturday Night Fever is a messy film. Wexler’s script features several underdeveloped subplots, including scenes with Tony’s brother, who decides to leave the priesthood; a gang rumble; and Bobby’s suicide. These heightened asides feel tertiary to Tony’s inner conflict, and such melodramatics only emphasize the rather clichéd portrait of his working-class turmoil. Still, most critics at the time were spellbound by Travolta and his undeniable energy, which, like disco, glosses over the seamier aspects of the character. The critical response amounted to a wildly positive reception at the time, with Gene Siskel eventually declaring Saturday Night Fever his favorite movie. Pauline Kael wrote a rave review, calling the film’s effect “nirvana” and praising how it depicts the allure of disco through Travolta’s screen presence. Most admired Badham’s direction and how cinematographer Ralf D. Bode shot the picture, using low, tilted angles to distort Tony’s world when he’s dancing, looking at himself in the mirror, or walking down the street. But like disco, the flamboyant visual style distracts from the story’s more grounded and realistic aspects.

Although the film deserves comparisons to Mean Streets for its portrait of the gritty street life in New York, Saturday Night Fever applies an empty Hollywood gloss to the proceedings that attempts to neutralize its thornier details. Too often, the film derives its pleasures from surfaces and never tackles Tony’s behavior, aping the style of better, more authentic 1970s cinema with similar themes. But here, the film’s occasional sheen was actively designed by Stigwood to sell records—to give audiences a “fever” that would cause them to ignore or make excuses for everything else. Many remember the film as a pleasant diversion, perhaps because they’ve only seen the PG-rated version, or maybe because they’ve opted for selective memory. Take Ebert, who observed, “After a few years what you remember is John Travolta on the dance floor in that classic white disco suit, and the Bee Gees on the soundtrack.” But even upon acknowledging what the film is versus what it’s remembered for, Saturday Night Fever only comes close to greatness before stumbling in the last fifteen minutes—which, for many viewers, have been repressed like a trauma, appropriately enough. Unfortunately, recollecting the pain doesn’t enrich the experience; it only reminds us that the film fails to deal with Tony Manero.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on August 3, 2023. Thanks to Diana for suggesting a film that, even though I didn’t love it, presented a challenging and engaging writing assignment—the best thing a critic could hope for. Thanks for your patronage and continued support!)

Bibliography:

Auster, Al, and Leonard Quart. “Review: Saturday Night Fever.” Cinéaste, vol. 8, no. 4, 1978, pp. 36–37. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42683443. Accessed 27 July 2023.

Ebert, Roger. “Great Movies: Saturday Night Fever.” RogerEbert.com, 7 March 1999. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-saturday-night-fever-1977. Accessed 27 July 2023.

Frank, Gillian. “Discophobia: Antigay Prejudice and the 1979 Backlash against Disco.” Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 16, no. 2, 2007, pp. 276–306. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30114235. Accessed 27 July 2023.

Kinder, Marsha. “Review: Saturday Night Fever.” Film Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 3, 1978, pp. 40–42. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1211725. Accessed 27 July 2023.

Powers, Richard. “Disco Lifestyle.” Stanford Dance. N.D. https://socialdance.stanford.edu/Syllabi/disco_lifestyle.htm. Accessed 27 July 2023.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review