‘Salem’s Lot

By Brian Eggert |

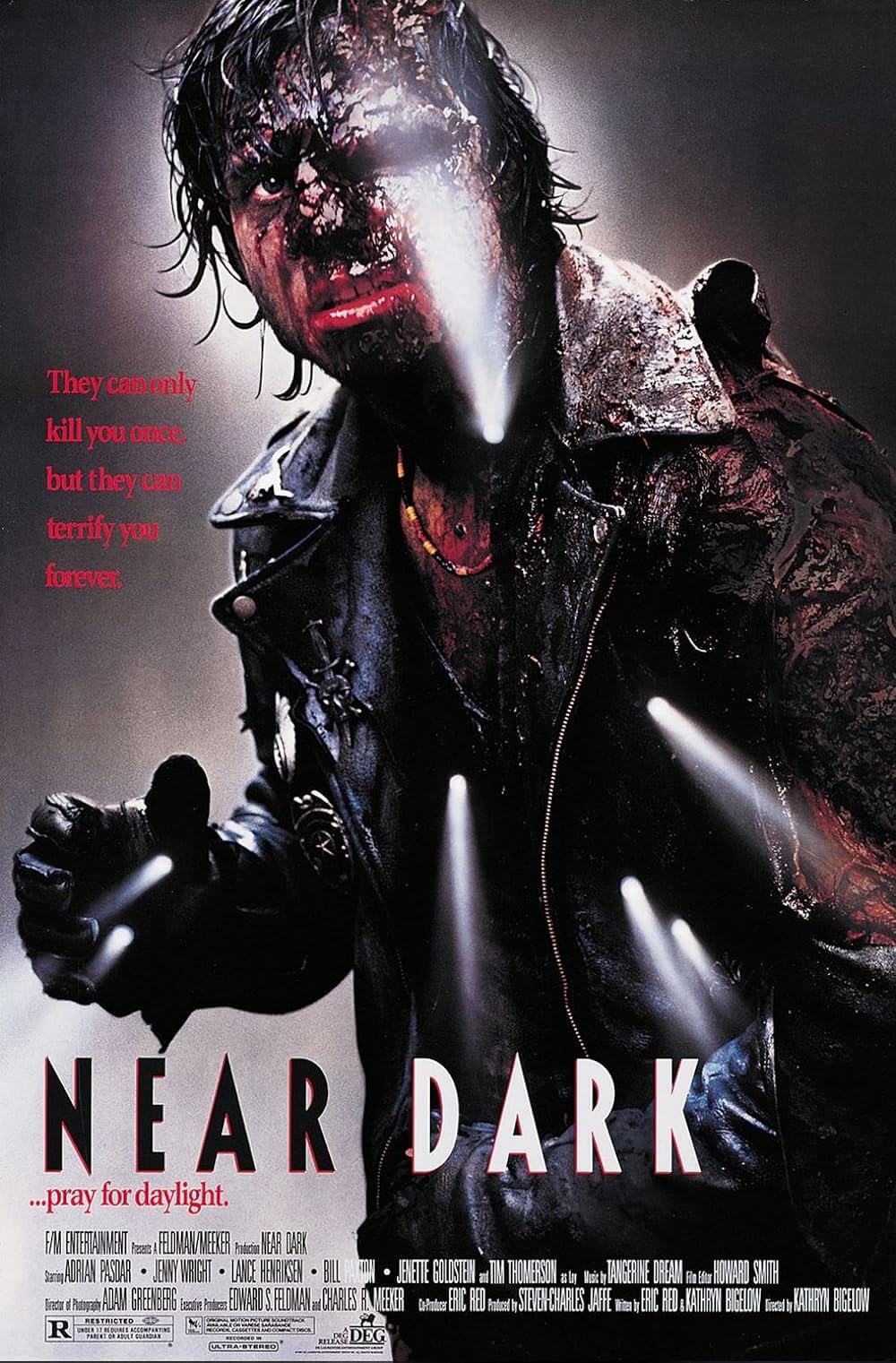

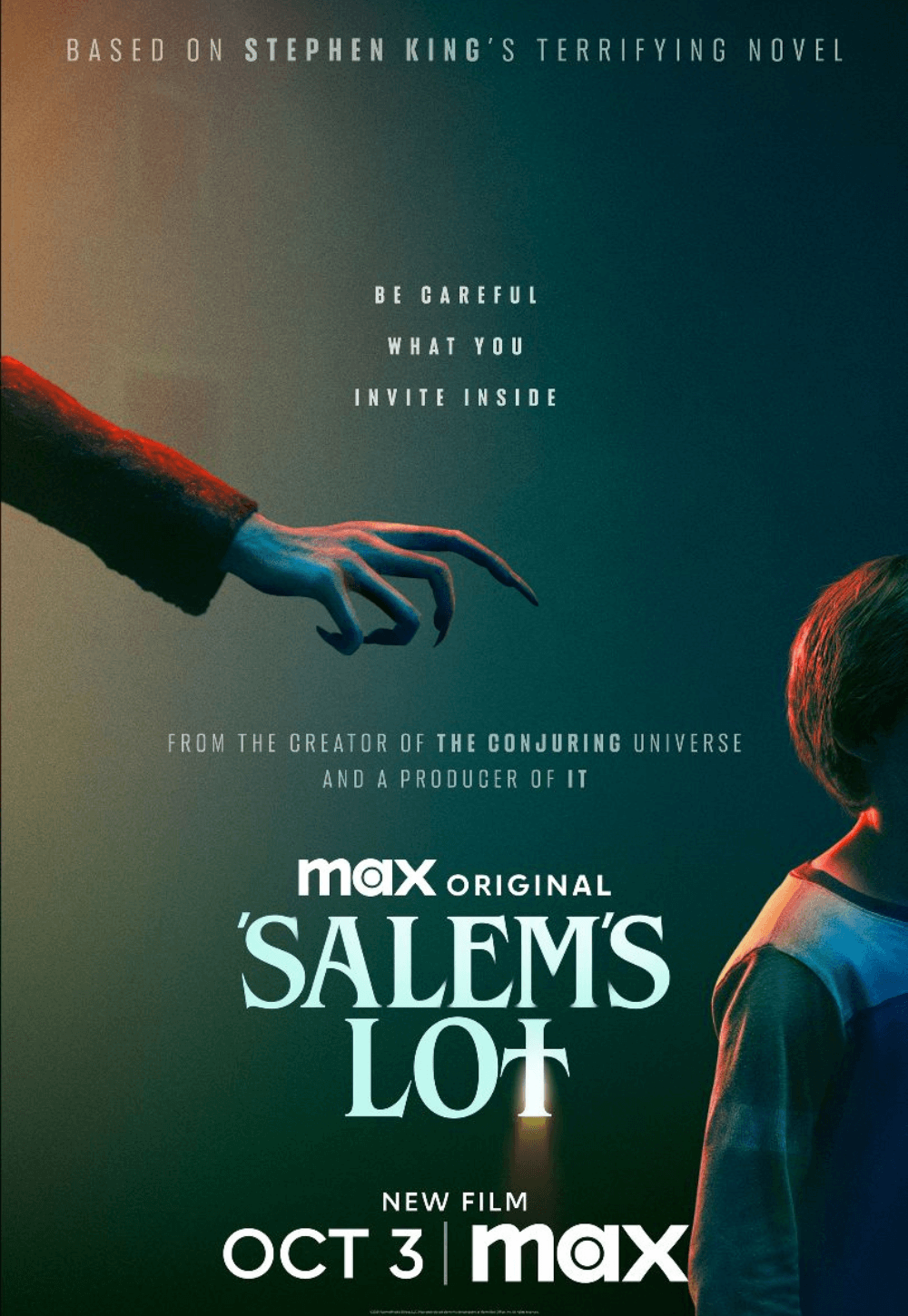

Why does the sun always go down faster in vampire movies? It’s as though the vampires have made a pact with Earth to spin faster and bring on the darkness at an accelerated pace. That, and plenty of other clichés, appear throughout ‘Salem’s Lot, the new adaptation of the 1975 book by Stephen King that’s exclusive to Max (formerly HBO Max, formerly HBO). But if such genre devices are still popular today, it’s reasonable to attribute them to the author’s book, at least to some extent. Along with Tobe Hooper’s excellent miniseries adaptation for prime-time television in 1979 (the less said about the 2004 miniseries, the better), King’s book helped turn vampires from the stuff of schlock movies into popular entertainment. Director Gary Dauberman’s new take deploys many tactics that have become vampire movie standards in the subsequent years, drawing both from the book and the nightmare-inducing imagery Hooper unleashed on his audience. However, instead of instilling the pervasive old-school dread and rich subplots that go with an entire small town succumbing to the darkness, Dauberman’s ‘Salem’s Lot resorts to contemporary techniques, demonstrating a clear preference for amped-up scares over fully realized characters or a slow-burning narrative.

Even so, the new ‘Salem’s Lot is a thoroughly watchable affair, enhanced by good casting, solid performances, and a few effective stylistic flourishes. So why did Max delay the movie’s release for so long? The result is an entertaining vampire movie and King adaptation, better than some I’ve seen but not as good as others. It’s also the best movie in Dauberman’s credits, which include several entries in the Conjuring universe, such as Annabelle (2014) and The Nun (2018). And yet, the movie has sat on the shelves for years. (Observe how young Nicholas Crovetti, who plays kid vampire Danny Glick, appears in his scenes—those who watch Prime Video’s The Boys will note that Crovetti looks like he did about three seasons ago.) To be sure, Dauberman had completed principal photography in 2021 and some reshoots the following year, but delays due to COVID-19 and the SAG-AFTRA strike stalled the release. Rumblings that the movie was unreleasable soon perpetuated the belief that ‘Salem’s Lot would be a disaster. However, this is not the case.

Besides the compelling King book, Dauberman establishes a solid foundation with his cast. Lewis Pullman plays Ben Mears, a struggling author who returns to his childhood home of Jerusalem’s Lot in 1975 to research his next book. A sleepy hamlet in Maine, the town has a sordid past full of strange disappearances and witchcraft, much centered around the creepy old Marsten House. An outsider named Richard Straker (Pilou Asbæk) has purchased the house for his employer, Kurt Barlow, seemingly to open a new antique shop in the Lot. But the necessity of the shop—to welcome townsfolk in, allowing Straker and Barlow to convert them to their bloodsucking cause—plays less of a role in Dauberman’s screenplay than it did in previous iterations. The writer-director deals in shorthand storytelling here, making leaps to keep the story moving and to get to the monsters, even if his omissions sometimes raise logistical questions and sacrifice the depth of his characters. The early appearance of Barlow (Alexander Ward), a CGI-looking thing modeled after the Barlow in Hooper’s take, is indicative of Dauberman’s impatience and refusal to allow the creature’s offscreen presence to loom in the viewer’s mind before showing him.

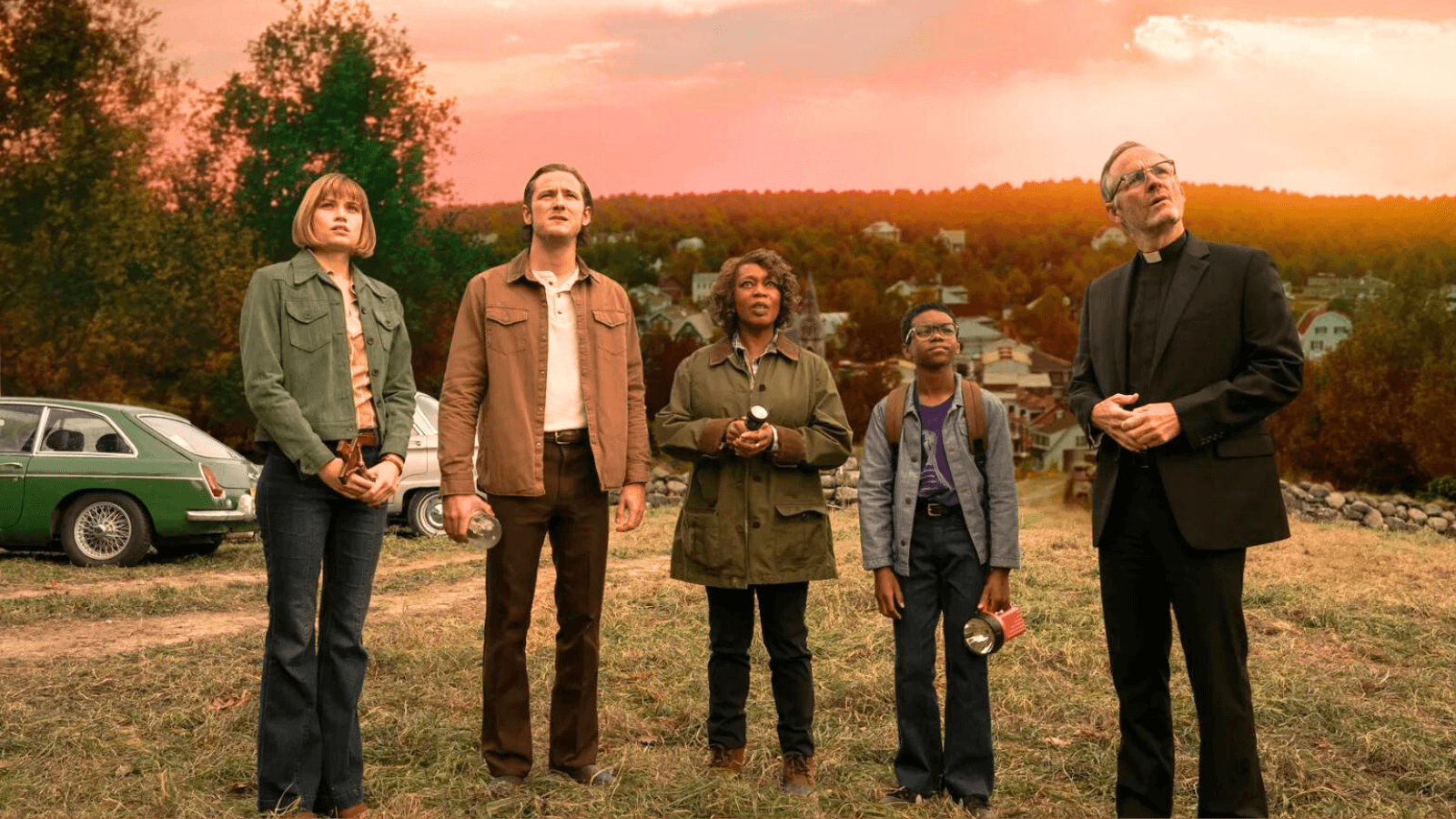

While Ben spends much of his time learning about the town’s history at the library, he becomes friendly with a young, aspiring real estate broker, Susan (Makenzie Leigh). The romance raises concerns among the locals, who view Ben as a dangerous outsider from the big city. That small-town paranoia is what King’s book was all about—the xenophobia and entrenched mistrust of everything we hold dear, brought about by the many failing political and social institutions of the 1970s, corrupting the lives of ordinary folk. Sure enough, Straker collects victims for his master, some for food, others as drones. Once the mortality rate begins to spike and corpses begin disappearing, it doesn’t take long for the word “vampire” to get tossed around. Ben finds allies not only in Susan but also in the bookish schoolteacher (Bill Camp) and skeptic doctor (Alfre Woodard). They’re joined by the preadolescent Mark (Jordan Preston Carter), another outsider in town whose affinity for horror movies and Houdini-brand magic has prepared him to fight the creatures of the night. Together, they wield crucifixes, which glow in the presence of vampires and serve as supernatural magnetic repulsors, and set out to stop Barlow.

While Ben spends much of his time learning about the town’s history at the library, he becomes friendly with a young, aspiring real estate broker, Susan (Makenzie Leigh). The romance raises concerns among the locals, who view Ben as a dangerous outsider from the big city. That small-town paranoia is what King’s book was all about—the xenophobia and entrenched mistrust of everything we hold dear, brought about by the many failing political and social institutions of the 1970s, corrupting the lives of ordinary folk. Sure enough, Straker collects victims for his master, some for food, others as drones. Once the mortality rate begins to spike and corpses begin disappearing, it doesn’t take long for the word “vampire” to get tossed around. Ben finds allies not only in Susan but also in the bookish schoolteacher (Bill Camp) and skeptic doctor (Alfre Woodard). They’re joined by the preadolescent Mark (Jordan Preston Carter), another outsider in town whose affinity for horror movies and Houdini-brand magic has prepared him to fight the creatures of the night. Together, they wield crucifixes, which glow in the presence of vampires and serve as supernatural magnetic repulsors, and set out to stop Barlow.

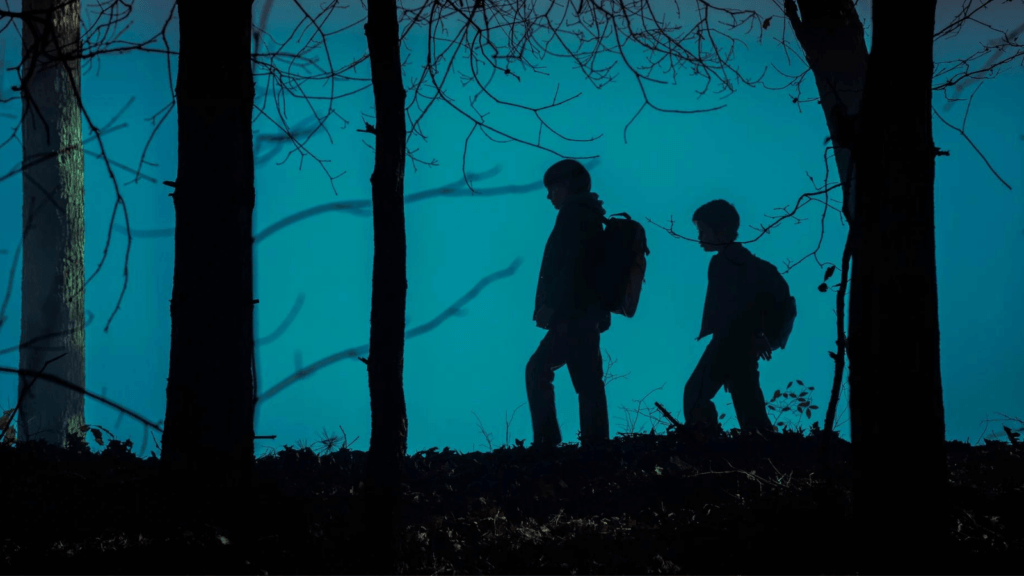

Although Dauberman’s treatment hits many of the expected story beats, he tends to over-emphasize the scares, which have a fast, sharp edge to them, more attributable to modern horror sensibilities than the Hammer-brand brooding King sought. Jump scares and shocker moments permeate the material, robbing the movie of its potential to get under the skin. Consider Asbæk’s performance in the Straker part once played by James Mason. Whereas Mason’s suave and businesslike charisma made him scarier, Asbæk has the look of an evil fanatic in his eyes, robbing the role of its potential nuance. Dauberman’s approach is broad, right down to the fiery finale, an actionized sequence set at a drive-in movie theater. He also owes a debt to Hooper’s version, drawing his vampire look and other details from the ’79 miniseries. Yet, Dauberman and cinematographer Michael Burgess create some memorable visuals, such as children silhouetted amid barren autumn trees, heading home through a forest at night, and pursued by Straker. The heightened colors of red, green, and blue hues also give the movie an uncanny vibe.

The most unfortunate aspect of Dauberman’s version is that it doesn’t last longer. At 113 minutes, the movie doesn’t have the time to explore the relationships that drove King’s story, nor does Dauberman prioritize them. Either a three-hour movie or a miniseries would have been preferable. Instead, the outcome plays like middling vampire fare, boosted by the assured cast and some unsettling visuals, such as the appearance of vampires with yellow, gemlike eyes stationed on buildings like gargoyles. But Dauberman’s persistent need to ramp things up and resolve the conflict, whereas King and Hooper left the story maddeningly but purposefully open-ended, reveals his commercial sensibilities. Dauberman was also the screenwriter of It (2017) and It Chapter Two (2019), adaptations that suffered from the same problems as ‘Salem’s Lot, suggesting that perhaps Dauberman’s interest in King doesn’t translate to understanding what makes King’s stories so memorable. It’s not just the iconic monsters; it’s the time King takes to flesh out characters before putting them into nightmarish situations. With the cast picking up the slack, ‘Salem’s Lot is serviceable vampire escapism, but one cannot help but feel the movie would have been something great had Dauberman taken a more measured approach.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review