Reader's Choice

Saint Laurent

By Brian Eggert |

Among the more fascinating details about Saint Laurent, Bertrand Bonello’s oblique film that ruminates on the revolutionary fashion designer, is that Yves Saint Laurent’s former lover and business partner, Pierre Bergé, did not endorse it. Bergé approved of the far more straightforward biopic directed by Jalil Lespert, called Yves Saint Laurent, which was also released in France in 2014. Lespert’s conventional drama hits every predictable beat, adopting a paint-by-numbers biographical structure that sought prestige attention, including a César Award for its lead actor, Pierre Niney. And though Bonello’s 2014 film earned multiple César Award nominations, several more than Lespert’s film—it won none of them—it also takes a more complex view of its subject. Instead of aggrandizing Yves Saint Laurent’s legacy and building his myth into a cinematic commercial for the YSL brand, Bonello invests himself in the complex and broken person—played in a committed internal performance by Gaspard Ulliel—who created some of the most iconic fashion lines of the twentieth century. Rather than a hagiography, Bonello confronts his subject’s personhood without dwelling on his genius, leaving viewers with no clear sense of how one should feel about Yves Saint Laurent. That’s part of what makes the film so exceptional.

Saint Laurent makes the case that great art doesn’t have to come from great people. Given this, it’s interesting to consider what Bonello thinks of his subject, whether he appreciates him as an artist or detests certain aspects of Yves’ behavior and his company’s influence. The aural presence of a radio broadcast about 1970s beauty standards critiques the in-vogue trend of ultra-thin women and how that can influence young women negatively, shaping their sense of self and body image. I wondered if this was a sly message implanted by Bonello, whose daughter, Anna, was a preadolescent at the time. Bonello often makes films in relation to her, from his portrait of disaffected and rebellious youth in Nocturama (2016), dedicated to Anna, to his tale of a teenage girl’s pandemic isolation in Coma (2022). The writer-director lends an impressionistic view of the designer’s life, exploring how, though Yves yearned for the orderliness of a Rothko painting, his life was chaos. Bonello doesn’t invent conflicts for Yves to overcome or personal demons for him to conquer. Though fame, success, drugs, and power shape much of his life, they never become keys to unlock answers to his behavior.

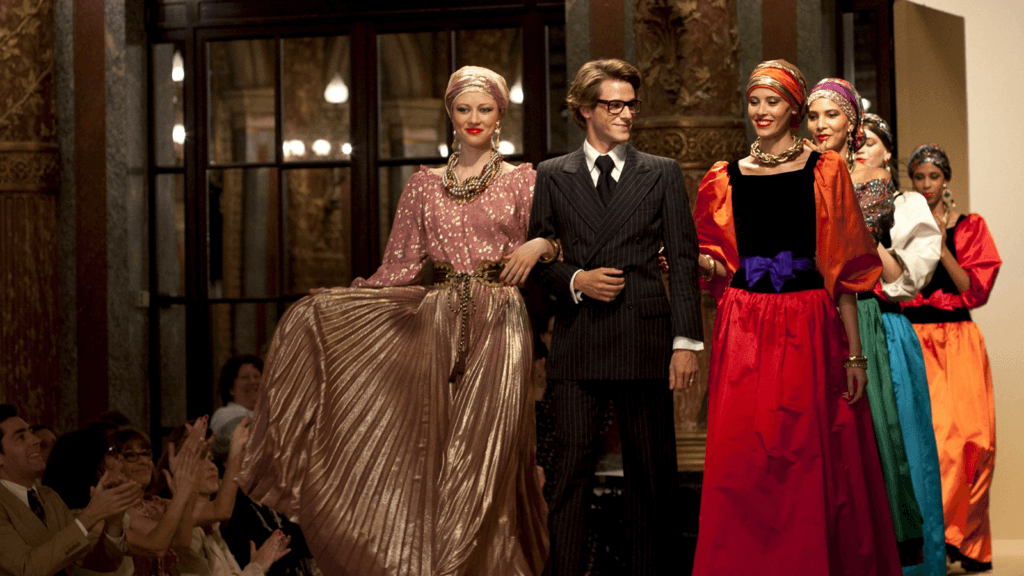

Bonello’s script quotes Andy Warhol, who said, “Fashion is as fleeting as advertising. That’s what makes it sublime.” Applying that sentiment to Yves, the filmmaker demonstrates an appreciation of transitory surfaces—all those pretty details and textures assembled by the designer’s house of patternmakers and sewists, beleaguered by the demands of their meticulous boss, that come and go with the times. Costume designer Anaïs Romand recreates many of the styles and garments associated with YSL’s heyday between 1967 and the early 1970s. Romand worked without the support of YSL’s archive and battled Bergé for access. Regardless, she reproduced gorgeous surfaces and superficial details. Even while Yves remains immersed in this beauty, Bonello shows his isolation—sometimes physical but primarily existential. He is uncannily played by Ulliel, himself a model, who was set to appear in Bonello’s 2024 picture The Beast before dying after a skiing accident in 2022. Ulliel might have continued to be the inspired muse of a filmmaker who often mines the rich complexities of identity for cinema that’s unparalleled in its multifacetedness.

Setting aside Bonello’s motivations for telling this story, his narrative adopts a fluid chronology that might play best for those unversed in the landmarks of Yves’ life and career. The film opens in 1974, with Yves checking into a hotel under a false name “to sleep.” This opener precedes a leap back to 1967, more than a decade after Yves started working for the House of Dior and a few years after Yves started YSL with his romantic partner, Bergé (Jérémie Renier). Never mind how Yves became interested in fashion design, where he trained, or who influenced him. Never mind where he grew up, what his childhood was like, or when he received his big break. Brief references allude to his past, such as his birthplace in Oran, Algeria. A line of dialogue or two hints at his conscription into military service in 1960 for the Algerian War, followed by crippling stress that landed him in a hospital, which loaded him with tranquilizers and subjected him to shock therapy. The film also depicts business meetings between Bergé and American executives, led by David (Brady Corbet), about combining haute couture with ready-to-wear practicality, lending a cursory look at how YSL changed fashion. But Saint Laurent isn’t a visualization of his Wikipedia page, as many biopics tend to be.

Bonello decontextualizes Yves in a manner comparable to how his subject rethinks styles from the past, sometimes to controversial effect. Consider YSL’s 1971 line “Homage aux Années 40s,” partly inspired by the elegance of Hollywood starlets from the Golden Age. Yves’ designs evoke a style last seen in Nazi-occupied Paris, such as fox-fur “chubbies” and tuxedo jackets on women. His appreciation of such surfaces could lead to controversy, yet he remained focused on building up artifices around him. Bonello crafts a personality that would later resemble Reynolds Woodcock from Phantom Thread (2017), which subtly draws from Saint Laurent in its portrait of a fashion genius who also happens to be a ridiculous, even terrible person. In one scene, a YSL garment maker needs time off to obtain an abortion. Yves pays for the procedure and tells her not to worry, behaving as though he’s generous, understanding, and even benevolent. A moment later, he tells her boss that he would prefer she doesn’t return to work. Any tumorous appearance of reality must be cut out.

Instead of romanticizing the glamor as Yves does, much of Saint Laurent consists of Yves’ sense of alienation despite always having an entire company, staff, and entourage around him. He soothes his isolation with self-destructive behavior, losing himself in a constant influx of alcohol, a rainbow of pills, and the occasional spoonful of chocolate mousse. Saint Laurent runs two-and-a-half hours, much of which consists of a numbed haze. When he’s not hunched over a sketchpad and conceiving new designs, he’s taking drugs and lazing around on oriental rugs or attending posh parties with his inner circle, feeling alone. Such repetitive sequences have a hypnotic quality, such as when he first spots model Betty Catroux (Aymeline Valade) in a club. Already working for Chanel, she turns down his offer to join YSL. “I can’t,” she says. “I’m asking you,” he replies. And around they go like that on repeat until, when we see her next, she’s working for him. Similar trancelike sequences involve Yves’ relationship with Jacques de Bascher (Louis Garrel), among them orgies of pill-popping and sex, leading to inevitable lessons about the dangers of excess. More fascinating is Loulou de la Falaise (Léa Seydoux), a peripheral figure whose sense of haute couture consists of thrift buys and visual contrasts, observing that “fashion passes like a train.”

It’s appropriate, then, that Bonello and editor Fabrice Rouaud establish a vibe-movie fluidity to Saint Laurent, marked by an elusive structure and sometimes hallucinatory imagery. Among the most formally bold sequences is a montage of YSL’s seasonal fashion lines on a split screen opposite archival footage of the social unrest in France from 1968 to 1971, marking a sly juxtaposition between the outwardly trivial and the urgency of political change. Bonello’s consideration of surfaces rivals that of a Sophia Coppola film. But it’s in service of his subject, who, even when alone, obsesses over arranging random objects into aesthetically pleasing patterns. After 90 minutes of screentime, Bonello begins flashing forward to 1989, where Helmut Berger plays the eponymous designer, who yearns to look like Johnny Halliday. While his designs are usually classical and mysterious, his latest “Russian” line of frilly, painterly dresses and turbans breaks the pattern, as though Yves based an entire style on Loulou’s attire. Still, the scene near the conclusion—where reporters, following false information that Yves has died, plan his obituary—encapsulates Bonello’s perspective: Even in death, an artist’s influence cannot be summarized. It continues like a ghost, or more accurately, a second life, long after they have passed.

Yves Saint Laurent’s approach to fashion opposes Bonello’s directorial interest in the designer. Whereas Yves remarks at one point that he prefers “bodies without souls,” the surfaces of things, the latter prefers to crack that surface and explore the mess spilling out—an approach that caused much resistance among American critics upon the film’s release. A lesser version of this biopic might try to explain Yves’ idiosyncrasies and particularities in a manner like Citizen Kane (1941), which famously suggests Kane’s childhood sled Rosebud represents the youthful joy that eluded him—a motif that, while overwhelmingly effective in Orson Welles’ treatment, has been borrowed by far too many film biographies since. Instead, clues to Yves’ identity can be found in remarks such as when Jacques tells him, “You really are a spoiled child.” Among the most telling episodes is when Yves’ staff tries to replace his dog Moujik after the animal dies because of Yves’ carelessness. Eventually, he goes through several dogs named Moujik, all to soothe his loss with the appearance of the original. This is the core of Bonello’s interest in Yves, a man who misguidedly believed aesthetic sublimity alone could make him whole.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on July 13, 2024.)

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review