Rustin

By Brian Eggert |

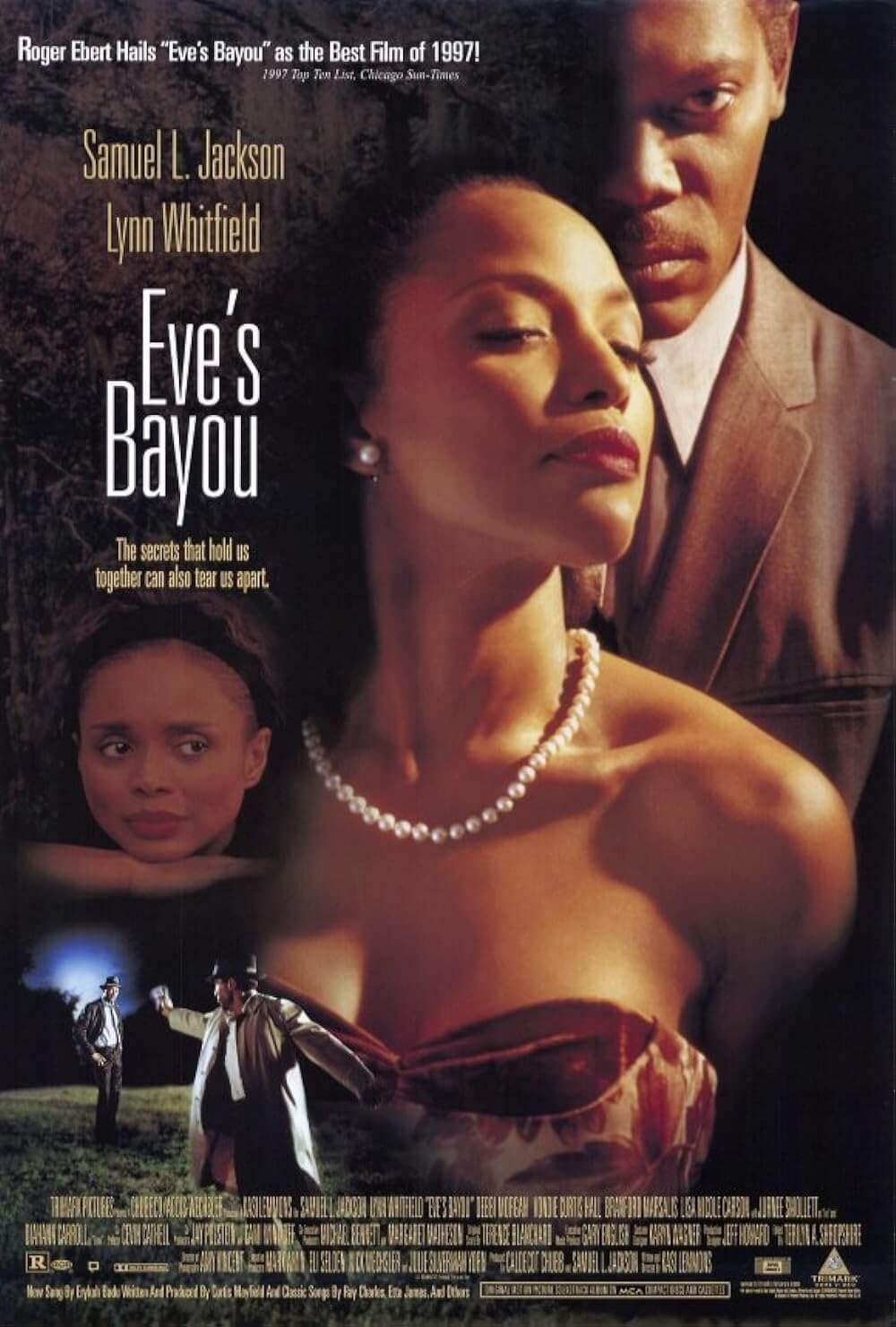

An American civil rights activist and adviser to Martin Luther King, Jr., Bayard Rustin was a gay Black man who today remains a somewhat forgotten historical figure. He organized significant peaceful protests against racial segregation—including the March on Washington in 1963—but bigotry over his sexuality kept him out of the spotlight. Netflix’s new drama about his cultural impact, Rustin, delivers a capable production directed by George C. Wolfe, whose last feature, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020), had more life pouring out of every scene and performance. Reteaming with the director, Colman Domingo plays the titular character in a showy turn, which finally grants the actor a lead role after years of reliable supporting work for filmmakers such as Spike Lee, Steven Spielberg, Lee Daniels, and Nia DaCosta. Wolfe’s direction is respectable but unassuming, while Rustin’s treatment of its subject is never more than straightforward. Still, for those interested in a chapter of history that will probably remain out of history schoolbooks for the foreseeable future, it’s a worthwhile but conventional movie about an unconventional person.

In detailing this overlooked historical figure’s life, screenwriters Julian Breece (When They See Us, 2019) and Dustin Lance Black (Milk, 2008) have a thankless task. So many historical biopics look the same or apply a similar narrative structure, making the genre too audience-friendly and predictable apart from the specifics. Films like this facilitate Oscar buzz because their treatment of historical figures often earns the attention of Academy voters, who love watching how well filmmakers recreate actual events and actors mimic real people’s mannerisms and vocal inflections. Thus, it becomes the filmmaker’s objective to frame the story in an unchallenging style that respects the people and events onscreen. With few exceptions—Malcolm X (1995), Jackie (2016), Tesla (2020), Priscilla (2023), to name four—the results rarely advance the medium of cinema, but those unversed in this period of American history or teachers looking to pad their lessons with an in-class movie now have a new option to learn from and teach.

At the very least, Rustin’s life doesn’t conform to many of his contemporary civil rights leaders. Raised a Quaker in Pennsylvania, he was also defiantly and openly gay, a fact that led to the suppression of his name—particularly after his 1953 arrest for homosexuality, which made him a registered sex offender in a less tolerant world. And though later in life he became involved in the gay rights movement, he spent most of his years arranging nonviolent protests against racial violence. His life was even more fascinating and multilayered than the production suggests. For instance, after appearing on Broadway in the chorus of John Henry and recording an album called Elizabethan Songs and Negro Spirituals, he visited India to learn strategies of nonviolent protest from Mahatma Gandhi. Most of these details go underserviced or altogether unmentioned in the film, however. Given his unique background, it’s disappointing that Rustin avoids the birth-life-death biopic structure and attempts to understand its subject through a singular event—the March on Washington, which he describes in typically expositional dialogue as “the largest peaceful protest in the history of this nation.”

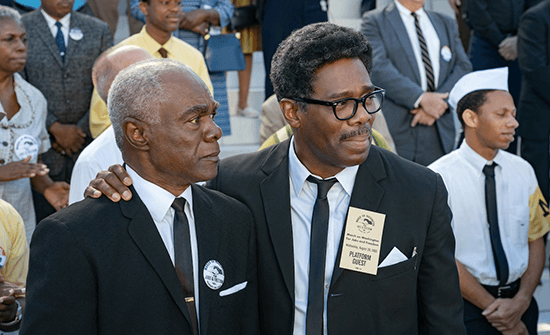

The film opens in 1960, six years after the Supreme Court ruled that segregation was unconstitutional. Even so, widespread anti-Black violence persists, prompting Rustin’s mission to make a bold statement the US government and the nation at large cannot ignore. Working alongside a group of young people, he coordinates volunteers, arranges meetings for supporters, enlists local police, and confronts politicians. Rustin also juggles a personal relationship with his lover, Tom (Gus Halper), and the various conflicting perspectives inside the movement. These range from those of Dr. King (Aml Ameen), with whom he’s feuding, to the non-committal support of the NAACP, run by Roy Wilkins (Chris Rock, whose presence is distracting). But for every influential figure opposed to the March, such as Sen. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. (Jeffrey Wright), who calls out Rustin’s gay identity, there’s a staunch supporter, such as union organizer A. Philip Randolph (Glynn Turman).

On a formal level, Rustin is functional at best. Andrew Mondshein’s nimble editing and the playful, swinging score by Branford Marsalis keep the proceedings moving in the first half. Production designer Mark Ricker and costume designer Toni-Leslie James give Rustin the superficial appearance of authenticity, as long as you don’t look too closely at the copious wigs and false facial hair, which make the actors look as though they’re playing dress-up rather than inhabiting their roles. Aside from a flashback in black and white, cinematographer Tobias A. Schliessler shoots mostly in crisp medium shots and close-ups, accommodating the Netflix viewing audience with an aesthetic that will look good on television or smaller devices. This approach also spares Wolfe from testing his budget with full-scale recreations of the March, leaving the final sequence where King gives his famous “I Have a Dream” speech to feel like a modest gathering instead of a monumental one. Wolfe prefers to train his camera on spectators who nod in approval, robbing the viewer of any scope or sense of what it might have been like to be there.

Like many biopics of this kind, Rustin may inspire viewers to learn more by seeking out an in-depth book about its subject (there are several about him). As is, the film’s 106-minute runtime hardly has time to explore his inner life, besides brief moments when his personal relationships interrupt his first priority—his sociopolitical ambitions and goals for the civil rights movement. Most stirring is how Wolfe depicts the hypocrisy of some Black civil rights leaders who believe in equal rights based on race but not sexuality, and how Rustin combats that perspective. But it’s Domingo who carries every moment with his energetic, inspiring performance, which will surely find Netflix campaigning for him during awards season. Nevertheless, the by-the-numbers screenplay and filmmaking fail the actor with its lack of substance or innovation, and like many films about the movement, it ends on a note of victory, suggesting those equal rights issues are a matter of history, when anyone living in America today knows such a sentiment is woefully false.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review