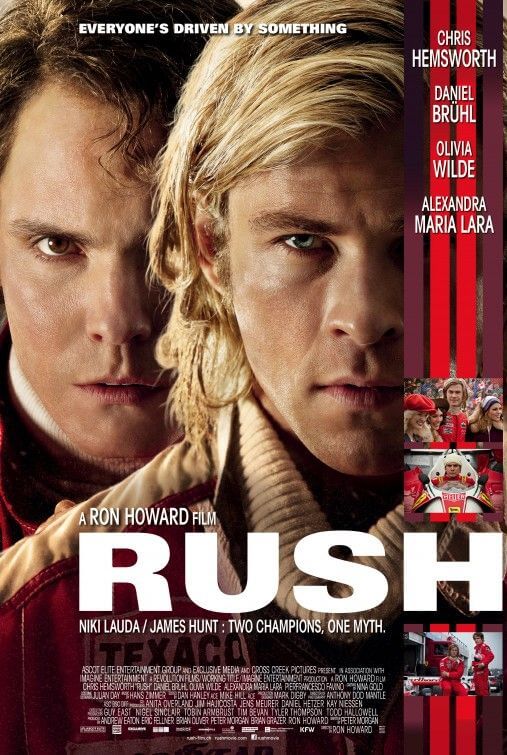

Rush

By Brian Eggert |

Ron Howard returns to the shaggy hair and muted visual palette of the 1970s with Rush, a drama about the rivalry between Formula One racers James Hunt and Niki Lauda during the 1976 racing season. Howard already explored this era to expert effect in Frost/Nixon, his cinematographer’s grainy visuals occupying the look of the time; and what’s more, he explored car chases in Grand Theft Auto, the director’s sophomore effort back in 1977. Reteaming with Frost/Nixon screenwriter Peter Morgan, Howard’s production channels similar racing films such as John Frankenheimer’s outstanding Grand Prix (1966) or Tony Scott’s not-so-great Days of Thunder (1990), except Rush is less about the races themselves than the drivers who risk their melodramatic personal lives through their often self-destructive need-for-speed.

Chris Hemsworth and Daniel Brühl’s performances as the speedsters are the primary reason to see the film, playing, respectively, British party animal James Hunt and the misanthropic Austrian, Niki Lauda. Both actors fully embody their roles (though Hemsworth’s bombastitude does contain shades of his turn as the Norse God of Thunder in Thor). Hunt lives on the edge, filling his downtime with countless women and substances. Somewhat embarrassing are scenes where Hunt loses himself in drink when he’s unable to find “a drive,” the editing filled with choppy clips of Hemsworth stumbling around, snorting cocaine, downing another mouthful of booze. He’s readily aware that his “closeness to death” is his appeal, and he embraces that quality to the fullest. Hemsworth’s charm and chummy smile serve him well in the role. Conversely, Brühl, best known for Inglourious Basterds, has the more complicated role. Lauda’s more of a purist, designing his own car to exact specifications and abstaining from all distractions to focus on the race. He’s determined and unflinching, and he doesn’t care if he’s liked by anyone. On the track, it’s a battle of philosophies: Hunt’s raw talent and instinct vs. Lauda’s meticulousness.

Morgan’s script spends less time on the competition and races than it does exploring the personal lives of its two central characters, so Rush isn’t merely a sports movie but an adult drama. And an R-rated one at that. Remaining steadfast in his vision, Howard has admirably left in swearing and nudity that could have easily been cut to gain a more commercially viable PG-13 rating. We must respect Howard for not selling out like so many other filmmakers as of late. But the story’s jealous concentration on Hunt and Lauda doesn’t allow for any supporting characters to become more than one-note filler, and this includes their eventual wives. The characters’ trajectories are such that Hunt finds himself married, albeit briefly, to dull model Suzy Miller (Olivia Wilde), while Lauda questions his desire to race after he meets Marlene (Alexandra Maria Lara).

As the story unfolds, Lauda, a banker’s son, moves up from F3 to F1 by buying his spot on the Ferrari team, whereas the less reliable Hunt must beg his way onto McLaren. Their ongoing opposition comes with plenty of insults, Hunt calling the rodent-faced Lauda his “ratty little friend” and Lauda cutting deeper by attacking his opponent’s rocky personal life. The story jumps around with the ever-winning Lauda in the lead and Hunt a close second, hurrying past the year’s early races in Sao Paulo, South Africa, or Spain. But things slow down during the fateful Nürburgring, Germany race that lands Lauda in a devastating, fiery crash, after which he’s left gorily scorched and hospitalized (shown in grisly detail). Yet he’s determined to race again before the season ends. For many unfamiliar with the real-life ending (myself included), the scenes leading up to and including the final showdown will contain an added thrill, as we’re unaware of the documented outcome.

For the small percentage of the audience with previous knowledge of Hunt and Lauda’s competition, there’s at least Howard’s technically proficient staging of the race scenes—although his frequent use of slow-motion during the rainy races in Germany and Japan makes the film look like a Mountain Dew commercial at times. Nevertheless, pit crew banter reminds us how F1 racing in the 1970s involved drivers sitting atop what ostensibly is a fragile bomb running at 450 horsepower. At any moment, a car could easily spin out of control and shatter or explode, costing the life of whoever’s behind the wheel. What other sport averages two competitors dead each year? Still, because Howard spends less time on driving than he does exploring the racers’ lives, we’re never quite involved in edge-of-your-seat suspense during the races. Of course, we want to know who wins, but the filmmaking lacks the adrenaline rush suggested by the title.

Rush is a capably made picture about a pair of enemies who, predictably, realize they need and feed off each other through healthy competition. Many of Howard’s choices are equally obvious, such as his uses of Steve Winwood’s “Gimmie Some Lovin” and David Bowie’s “Fame” on the soundtrack, which make the film seem like a movie trailer. For a better balance between involving races and the off-track melodrama of F1 drivers, see Frankenheimer’s aforementioned three-hour epic Grand Prix, which Howard has openly admitted was his inspiration here. Frankenheimer’s film dwells on the races and uses early in-car camerawork to transform what is essentially a boring, monotonous competition that just goes round and round into a dramatic, exhilarating stage for the off-track drama. Whereas Frankenheimer found an equilibrium between his drivers’ complicated lives and their races, Howards’ film is unbalanced, leaving the races feeling secondary and even incidental next to the rivalry between Hunt and Lauda.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review