RoboCop

By Brian Eggert |

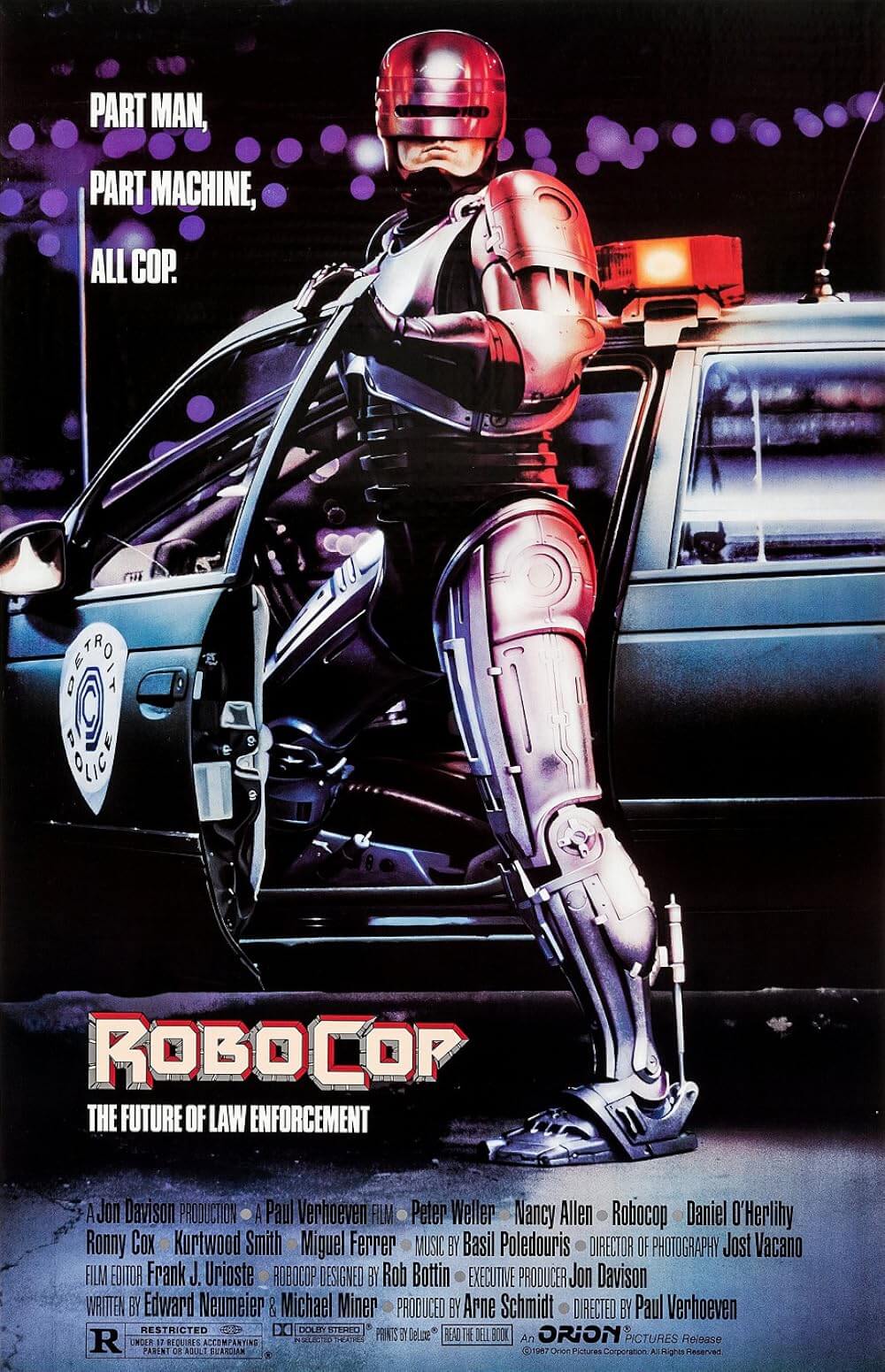

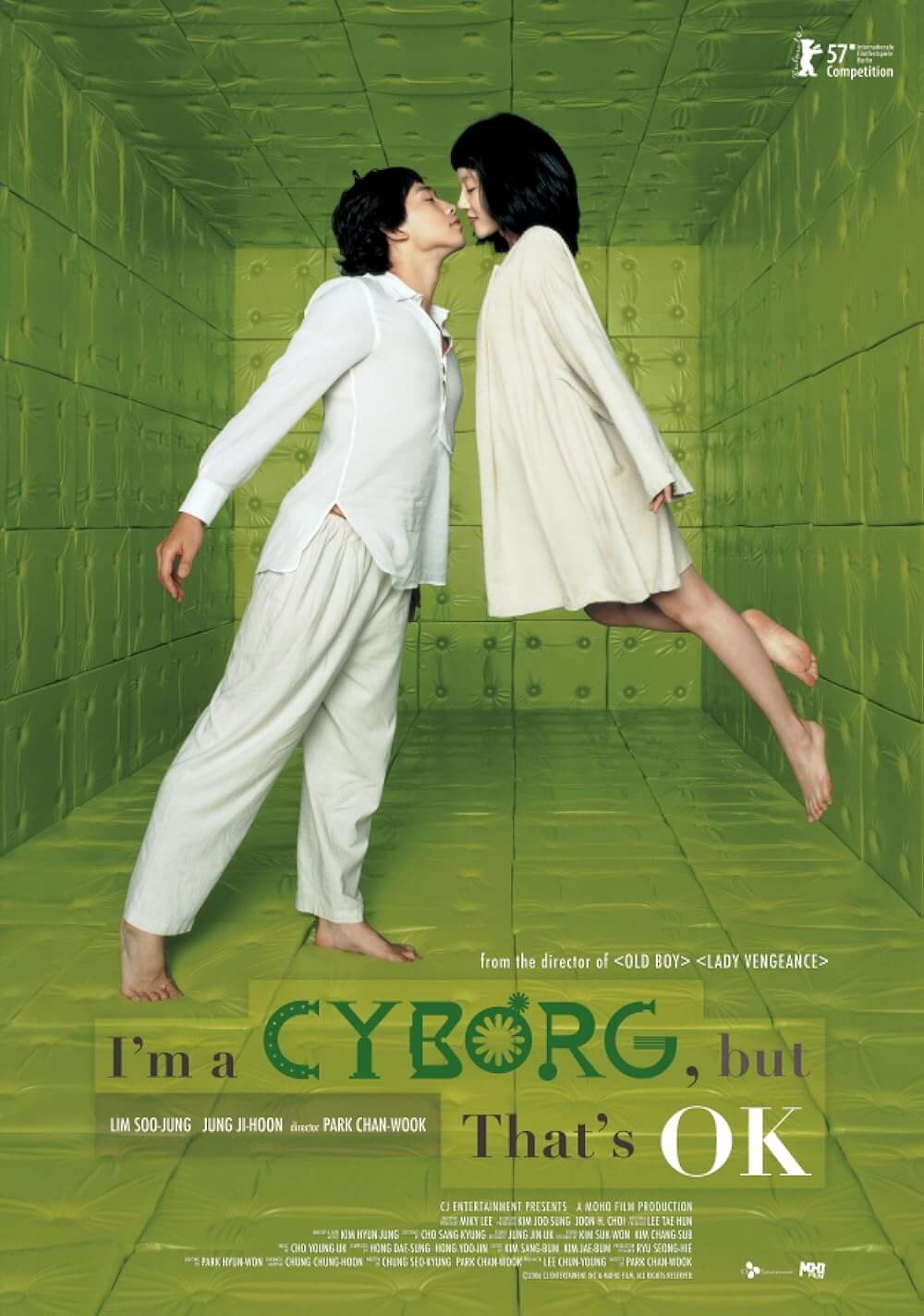

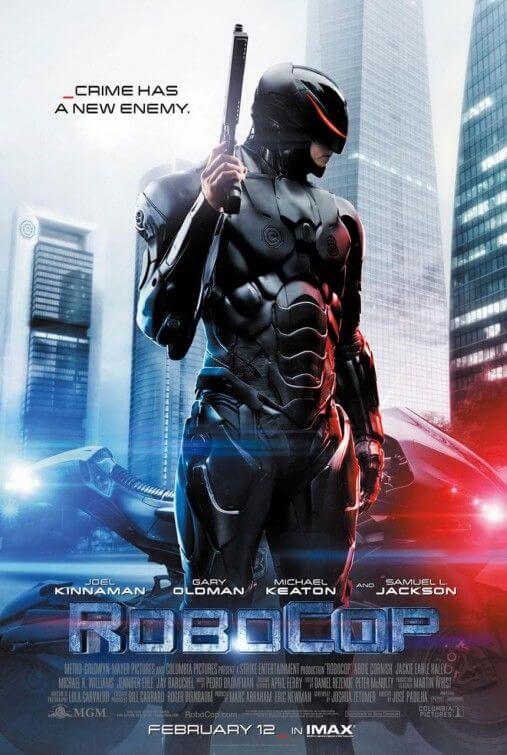

Remaking Paul Verhoeven’s bloodily comic satire RoboCop is a thorny prospect in terms of crowd-pleasing, in that the 1987 film’s enthusiastic cult following demands the outcome achieve a careful balance of homage and artistic deviation, while younger generations unfamiliar with Verhoeven’s original have their own high expectations for science-fiction actioners of this sort. Fortunately, the 2014 remake adopts an effective approach to the standard Hollywood reboot, following a prescribed norm for contemporary franchises by embedding gravitas and emotion into a darker, more realistic, yet utterly fantastical scenario. The new RoboCop, from Brazilian director Jose Padilha (the Elite Squad series), keeps a few basic elements from the original intact—along with some of the remake’s superficial resemblances to its source, both films involve a hero cop shot down in his prime and turned into a cyborg, both feature an evil corporation which manipulates our hero, and both contain themes of humanity emerging from technology. But Padilha’s film is a beast all its own, and once it starts, the viewer rarely looks back or gets caught up in the many differences between the new and original versions.

The script is credited to Joshua Zetumer, but also to Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner, who wrote the original. One of the most interesting aspects of the remake’s script is the political backdrop, which is set in 2028 and involves a national debate over robotics in the United States. By way of ultra-conservative Fox Newsy personality Pat Novak (Samuel L. Jackson) on his show “The Novak Element”, we learn that congress has voted to prevent the use of robotic policing drones on American soil. Created by OmniCorp, the drones are employed in every country in the world except the U.S. and have resulted in dramatic decreases in crime and terrorism, not to mention the lives of American soldiers saved abroad. Novak asks, “Why are we so robo-phobic?” But he’s a spinster, cutting a live feed from the drones in Tehran just as OmniCorp’s ED-209 model unloads a shower of bullets on a child with a knife. As a result of the government’s decision, OmniCorp CEO Raymond Sellars (Michael Keaton), along with his legal and marketing team (Jennifer Ehle and Jay Baruchel), must resolve how to make an efficient robot with human consciousness and feelings to circumvent the law.

Luckily for OmniCorp, unfortunate for him, Detroit detective Alex Murphy (Joel Kinnaman, from AMC’s The Killing) is blown to smithereens by a car bomb after his investigation into a gun-smuggling ring leads him to dirty cops. With Alex left in tatters, his wife Clara (Abbie Cornish) hopes he can be salvaged and signs his barely alive remains off to OmniCorp and their lead scientist Dennett Norton (Gary Oldman), whose research thus far has been rooted in providing robotic prosthetics to amputees. Under Sellars and OmniCorp’s chief military guru Maddox (Jackie Earl Haley), Norton’s noble convictions soften as he turns Alex into a weaponized human being, his software soon faster than Maddox’s fully robotic drones. Much of the film occupies the development and testing phases of Alex’s emergence as RoboCop and how OmniCorp must always observe their monster to ensure he’s an appropriate marketing tool to sway voters. They monitor his whereabouts, thoughts, and how their programming reacts to his brain. And despite limiting Alex’s emotions, some part of his humanity overrides the software, and he’s impelled on missions of his own—to investigate his would-be murder and reconcile with his distraught family, including his traumatized son David (John Paul Ruttan).

The new RoboCop’s tone and world are less extreme, less satiric than the original (qualities which made Verhoeven’s film so singular), and more rooted in characters. The 1987 version employed pitch-black irony to send up America’s borderline-fascist Reagan-era ways from the Dutch director’s very liberal, European perspective. Padilha’s film, while engaging in a mild parody in “The Novak Element” scenes, concerns itself more with Alex’s family and the loss of humanity through corporate resubjectification. Underdeveloped are the subplots in which Murphy investigates his own would-be murder or the corruptive villainy of OmniCorp, but much time is spent on Alex and his family (who were consigned to the hero’s memories in the original), and his upsetting loss of human connection. Indeed, this is sad stuff, and involving too. Even if our time with Alex-before-the-bomb is limited, the tragic elements of the aftermath resonate on a dramatic level more than the original’s did, and prove affecting not only for Alex’s narrative arc but that of Oldman’s character as well. Meanwhile, the smart corporate atmosphere—informed by global and national politics, and by the marketing spin (at one point, Baruchel’s character announces, “He transforms… The kids are gonna love it!”)—gives the material weight. Overall, there aren’t as many layers as in Verhoeven’s film, but the evident layers are realized well.

Several references to Verhoeven’s original are littered throughout, but their presence doesn’t deviate much from the remake’s cohesion, unlike the sometimes nonsensical nods seen in another Verhoeven remake, 2012’s Total Recall. Carefully placed dialogue such as “I wouldn’t buy that for a dollar” will make the original’s fans smile, whereas Basil Poledouris’ original score played over the opening credits doesn’t quite fit the more somber tone of this film. And while Alex Murphy, originally played by Peter Weller, is one of the only characters carried over from Verhoeven’s version by name, Michael K. Williams appears in an underwritten role as Murphy’s partner Lewis (originally, Lewis was a woman played by Nancy Allen). Of course, the most recognizable carryover is RoboCop’s suit, a sleek-looking silver and black armor with a visor. Here, the visor flips up and gives Kinnaman’s face more screentime than Weller’s, which reflects Padilha’s emphasis on Alex’s humanity. But around halfway through the film, Sellars resolves to make RoboCop more “tactical” looking, and the suit is painted black, his visor now glowing red and making him look very Cylon-esque, but ultimately more distinct.

Originally planned for director Darren Aronofsky (Black Swan), the long-in-development remake has survived delays, critical responses to early behind-the-scenes photographs, and reports of studio tampering. But the rough road to the screen has resulted in an exciting and interesting film under Padilha, this being his first English-language production. The special effects look sharp, the impressive ensemble of character actors serves the material well, and the story departures from the original are very often interesting. The new RoboCop’s PG-13 rating means a marked lack of onscreen bloodshed, a drastic change to Verhoeven’s notoriously gory original, but the shortage of red onscreen is hardly missed. Without a doubt, comparisons to the original are unavoidable and in these discussions, Padilha’s film will always be defeated and considered inferior to its predecessor, which it is. Nevertheless, his film is a smarter-than-average actioner that may not be as fun or edgy as Verhoeven’s, but manages to do what remakes so often strive and fail to accomplish: It achieves a new take on an old classic and does so with enough innovation to warrant its existence.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review