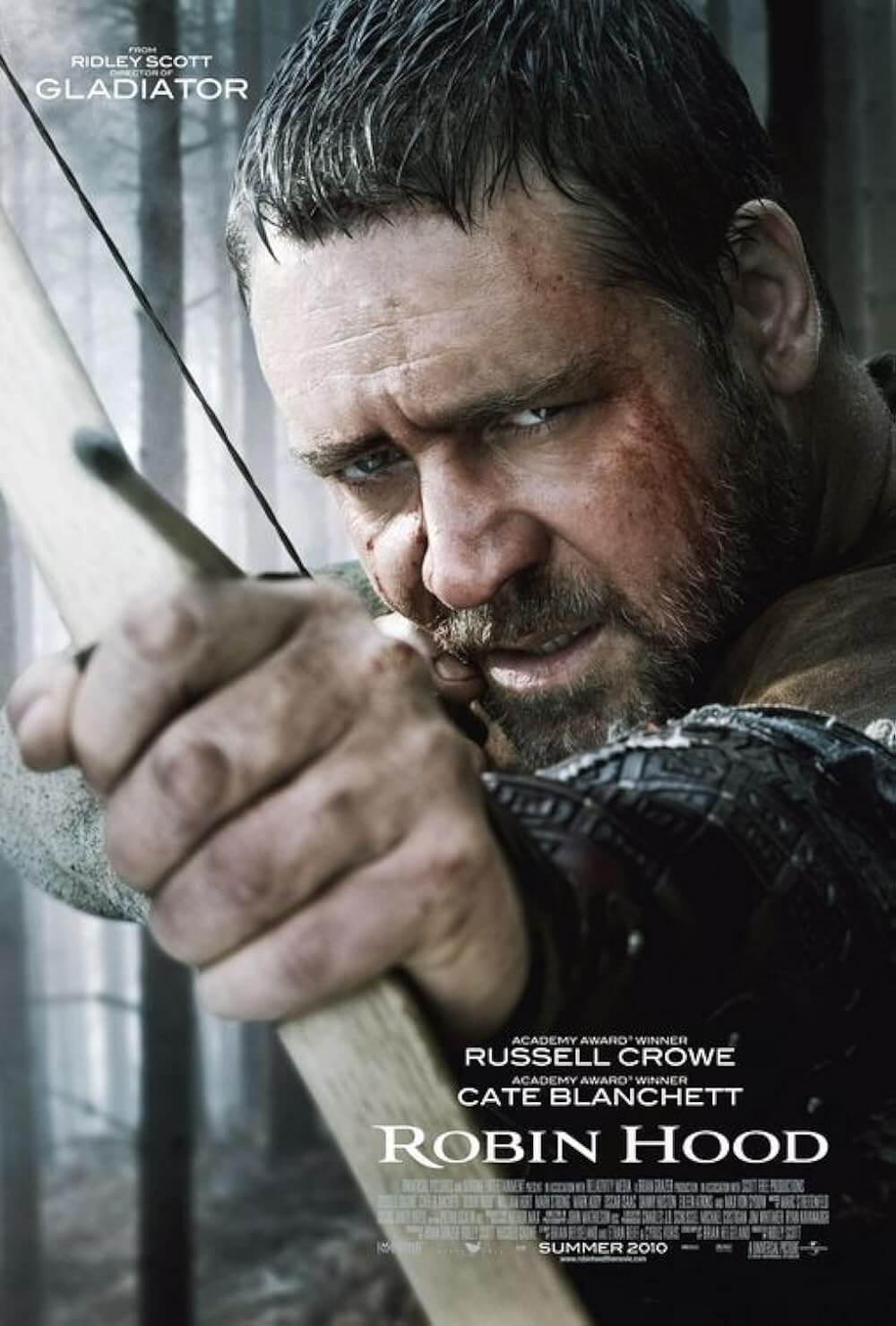

Robin Hood

By Brian Eggert |

Ridley Scott’s Robin Hood does not attempt an adaptation of the Robin Hood legend through fanciful, whimsical imagery. It avoids escapist, swashbuckling antics, and has no intention of being interpreted as a storybook. And yet, the majority of critics have made the mistake of comparing Scott’s film to 1938’s unparalleled The Adventures of Robin Hood, that unforgettable wonder starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland, a personal favorite of mine. What a mistake they’ve made. Scott’s film certainly contains less joy than the 1938 version, but it has no desire to compete with its predecessor, unlike some Robin Hood films of the past (such as Prince of Thieves, the film that sent Kevin Costner around Hollywood to disparage Flynn’s version). Indeed, Scott’s film attempts something different, unlike any Robin Hood film audiences have seen before.

In some ways, this is a critical error on Scott’s part, as the Robin Hood legend became as much by word of mouth, by storytellers aggrandizing and exaggerating the slim truths and turning them into something resembling fairy tales. And it’s those legends that have survived for centuries. But Scott wants to make Robin Hood an epic for adults, something on par with his own Gladiator and Kingdom of Heaven, with smatterings of legend-in-the-making mixed in for good measure. Seen from this perspective, Scott’s film is another gritty, Earth-toned, violent, and entertaining epic. Seen as a comparison piece to The Adventures of Robin Hood, well, how can any film, much less one about Robin Hood, compare to that timeless piece of filmmaking? Against the 1938 version, Scott’s film is an utterly joyless failure. But then, if audiences want to compare the two films, they’re missing the point entirely.

Filled with authentic details about 12th-century life in England, Scott’s production may not be able to claim one hundred percent historical accuracy in terms of the plot details, but it feels more realistic than previous adaptation. The story opens before Robin Longstride (Russell Crowe) becomes an outlaw known as Robin of the Hood. Our hero fights in the army of King Richard the Lionheart (Danny Huston) against France, and after enduring one too many unjust massacres, he deserts. On his return home, he and his cohorts (Kevin Durand as Little John, Scott Grimes as Will Scarlett, and Alan Doyle as squire Allan A’Dayle) come across an ambushed royal party led by Sir Robert of Locksley (Douglas Hodge). Robin promises Locksley to return his family sword to his father, Walter Locksley (Max von Sydow), in Nottingham. Once there, the elder Locksley asks Robin to act as Sir Robert to avoid losing his land to the king’s tax collectors. During this meet-cute device, Robin encounters his future love, Marian (Cate Blanchett), and makes friends with the village drunkard, Friar Tuck (Mark Addy).

Meanwhile, the wicked Prince John (Oscar Isaac) takes his place as king, creating a bad name for the throne by over-taxing his people to pay for his mistakes. Witnessing how the kingdom is divided under its current reign, John’s duplicitous servant and soldier Godfrey (Mark Strong) makes an alliance with the French and secretly plans an invasion, while also creating chaos in the countryside by pillaging in King John’s name. To restore order to the broken and disenchanted English populace, Robin helps convince John to agree to sign a charter (later known as the Magna Carta) that would allow the king’s subjects certain human rights and privileges. With their charter promised to them, Robin leads the newly joined forces of England in a harrowing battle against the invading French.

The screenplay by Brian Helgeland (L.A. Confidential and Mystic River) contains some rather cleverly disguised allusions to contemporary politics, much like Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven. Both films make parallels between the strongest countries in their time senselessly heading out into the world to make trouble, all while there are plenty of problems on the home front to contend with. Surely, there’s something to be said for Robin Hood standing up to King Richard at the beginning of the film, condemning the country’s senseless slaughter of Muslims during the Crusades, and then abandoning his army. Such bold thematic notes in the subtext will resound with audiences looking to relate this material to today.

Helgeland also avoids your typical epic dialogue, with a surprising omission of any needless, Braveheart-like speech to the troops. And the very stirring, very British language is spoken by talented actors capable of delivering that dialogue with class and conviction. When someone like The Seventh Seal’s Von Sydow utters a weighty story about Robin’s past, we cling to every word. Or there’s Blanchett’s feminist Marian, whom the actress makes both vulnerable and empowered in the same breath. And yes, Crowe makes a different, certainly revisionist version of Robin Hood (at 45, Crowe is the oldest actor ever to play the role), but he’s altogether a likable lead. He’s an actor who’s able to remain affable in lighthearted scenes with his pre-Merry Men and yet scowl through his battle cries while clashing swords with Godfrey.

As always, Scott knows how to compose a grandiose, visually striking battle, complete with waves of arrows flying and lines of soldiers charging at one another. But the battles are less imposing than the characters, who lay the considerable groundwork for a much-anticipated sequel if indeed it was the filmmakers’ intention to continue with the story. What would follow after the end of Robin Hood is the archetypal legend of the hero putting an end to Prince John’s tyranny, establishing himself as a folk hero based in Sherwood Forest, and clashing with the Sheriff of Nottingham (who here, as played by Matthew Macfadyen, makes only brief appearances on the periphery). But if the negative press about this film succeeds, and no sequel is made, there’s no harm done aside from some mild disappointment. The traditional Robin Hood tale involves impossible heroics, the stuff of legends and storybooks. And Scott’s film isn’t about standard fiction or fantastical escapism but about establishing a (highly Hollywoodized) version of the truth.

My opinion on Robin Hood is the minority one, which is unfortunate. Audiences willing to put aside the legend and the seemingly endless retellings of the same old story will find something worth treasuring in Scott’s film. It doesn’t do what we expect a Robin Hood film would; it doesn’t include archery competitions or swashbuckling swordplay. There are no green tights, and Crowe’s version of the hero doesn’t have a feather in his cap. In truth, he has no cap at all. But Robin Hood grasps the political and emotional climate of the legend, adding dimensions to the age-old tale that seems increasingly stale with each new interpretation. And while the film could never compare to The Adventures of Robin Hood, it doesn’t have to, because it offers us something completely different. In this case, different is good.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review