Road House

By Brian Eggert |

(Disclaimer: This movie was screened under the influence of a white cherry flavored ICEE, a favorite concessions treat of this critic, which has been unavailable at local movie theaters for many years. It may have contributed to the reviewer’s sense of elation. Thank you to the Mann Edina Theater for supplying the fix.)

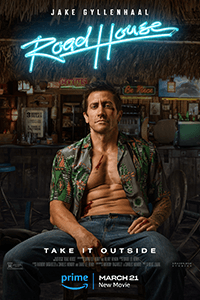

The original Road House from 1989 has developed a cult status thanks to our culture of irony. Writing in his book Mike Nelson’s Movie Megacheese, Nelson, the human host of later Mystery Science Theater 3000 seasons, called Road House “the single finest American film. Certainly it stinks, but I believe the filmmakers meant it to, and succeeded grandly.” Sure, some aspects deserve praise, such as the competent cinematography by legend Dean Cundey, Patrick Swayze’s genuinely impressive oiled-up physique, and Sam Elliott’s hair acting. But others don’t make much sense, including most of what happens, the characters’ motivations, and the appeal of a pungent shitkicker dive bar in the 1980s. Yes, the original is trash, but it’s entertaining trash. The same is true of the remake, directed by Doug Liman (The Bourne Identity, Edge of Tomorrow) and starring Jake Gyllenhaal. There’s no reason the movie needed to be made, but now that it exists, it’s pretty entertaining. Gyllenhaal’s star power accounts for much of the appeal, and it boasts a sardonic, self-aware silliness and gleeful, over-the-top quality that worked for me.

Resituating the story from a scuzzy Missouri nightspot to a roadside bar in the Florida Keys, Road House at least makes more sense than its predecessor did from a narrative standpoint. In response to local goons bringing a violent element into her bar, called the Road House, the owner, Frankie (Jessica Williams), sets out to locate a brawler (Austin Post) to protect her place. But when he proves too intimidated and backs out of a fight with a potential opponent, Dalton (Gyllenhaal), a former UFC fighter with a notorious past, she switches tactics. Frankie enlists Dalton instead, believing his celebrity and reputation will diffuse conflict before it starts. Dalton has become a borderline suicidal, off-the-grid drifter, still reeling from an incident that ended his career. Nevertheless, he accepts Frankie’s offer, bringing a smiley, polite energy to the job. But he quickly learns it’s more than throwing out a few rowdy individuals. It’s about protecting Frankie’s place from a shady douchebag businessman, Ben Brandt (Billy Magnussen), who’s willing to kill to secure the bar’s land for a development deal. Brandt even has a miniature scale model of his plan, standard issue for every ‘80s-style movie villain.

Screenwriters Anthony Bagarozzi and Charles Mondry don’t bother hiding that Road House, like the original, is a contemporary take on Western archetypes, where a lone gunman cleans up an unruly bar and corrupt town. It shares much in common with Michael Curtiz’s Dodge City (1939) and many other Western yarns. This is underscored by a plucky girl (Hannah Love Lanier) at a local bookstore, who describes Dalton as a cowboy hero, in case we didn’t make the connection. She eventually becomes the reason Dalton stays to fight Brandt. To be sure, Dalton’s presence recalls that of a gunslinger in how his reputation precedes him. After several dream sequences hint at the career-ending UFC incident, the movie reveals what he did and why everyone knows him. This made more sense to me than Swayze’s reputation in the original, which seems exclusive to an underground world of protecting shitty bars, so it’s strange that tales of his legend have reached far and wide. Still, in typical remake fashion, Road House features callbacks to the original, which are occasionally nonsensical given the new context. When Swayze’s Dalton says, “No one ever wins a fight,” he draws from the character’s stated background in philosophy. When Gyllenhaal’s version says the line, it registers as insincere and meaningless.

Liman brings his usual energy to this remake, forgoing the original’s throat rips for other, no less outlandish indulgences—personified by Knox, played by Irish MMA fighter Conor McGregor. He first appears in the movie naked, having just cuckolded another man, and then swaggers in the buff down to a local market, which he burns to the ground. A pure psychopath who drives fast, usually drunk, and pummels anyone in his way, he’s a dangerous, ridiculous, live-wire presence, and he steals every scene in which he appears. Also enjoyable is one of Ben’s thugs, played by Arturo Castro, an amusingly nice guy caught up with some bad people. Behind the bar, B.K. Cannon lends a pleasant personality to the bartender, while Lucas Gage and Dominique Columbus train to become Dalton’s fellow bouncers. Daniela Melchior takes on the nurse role originated by Kelly Lynch, and similar to the 1989 version, the romantic subplot feels engineered to introduce a “now it’s personal” conflict.

Liman brings his usual energy to this remake, forgoing the original’s throat rips for other, no less outlandish indulgences—personified by Knox, played by Irish MMA fighter Conor McGregor. He first appears in the movie naked, having just cuckolded another man, and then swaggers in the buff down to a local market, which he burns to the ground. A pure psychopath who drives fast, usually drunk, and pummels anyone in his way, he’s a dangerous, ridiculous, live-wire presence, and he steals every scene in which he appears. Also enjoyable is one of Ben’s thugs, played by Arturo Castro, an amusingly nice guy caught up with some bad people. Behind the bar, B.K. Cannon lends a pleasant personality to the bartender, while Lucas Gage and Dominique Columbus train to become Dalton’s fellow bouncers. Daniela Melchior takes on the nurse role originated by Kelly Lynch, and similar to the 1989 version, the romantic subplot feels engineered to introduce a “now it’s personal” conflict.

Road House features a few memorable fights, a death by crocodile, and, for some reason, a boat chase. Liman and cinematographer Henry Braham shoot the action with wide-angle lenses and close-quarters camerawork that captures the animal energy of UFC-style fights. Some other reviewers have complained about the CGI used to augment the fight sequences, which is a fair criticism. The scenes sometimes have a herky-jerky quality as the digital frame moves about a digital space, looking like a next-gen version of Mortal Kombat. So much CGI hardly seems necessary for a movie about people punching each other. Then again, if I were Gyllenhaal and were expected to act out a fight with McGregor, I would opt for computer-generated assistance too. The threat of McGregor landing an accidental blow to my precious face and charming smile would be too great to risk. Even so, many of these fights are fun to watch, including a random barroom brawl that feels like Liman’s ode to the famous one in Dodge City.

Liman has made a fuss in the press about Amazon MGM Studios’ choice to debut Road House on the Prime Video streaming platform, going so far as to boycott the premiere. Though, all information suggests streaming was always the plan, and Liman knew as much. That said, I caught the movie at a preview screening with an audience who fed off the contagious energy onscreen and in the auditorium. The movie would have performed well with crowds had it been released in theaters; it’s better in this setting than at home, on a tablet, laptop, or even a television, where most streaming debuts tend to feel disposable. The punch-drunk, larger-than-life quality of Road House felt appropriate in the theater setting, and perhaps that’s why I enjoyed watching it, albeit with plenty of reservations. But Gyllenhaal is an affable lead, most of the supporting actors fill their roles nicely, and the story hits all the necessary beats, arriving at the expected catharsis. The movie delivered. Then again, after the 1989 version, the bar was low.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review