River of Grass

By Brian Eggert |

Kelly Reichardt’s first film River of Grass could easily be confused with the work of another filmmaker. It debuted at the Sundance Film Festival in 1994, where it was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize, but Reichardt did not complete another feature-length project for over a decade. In the interim, her aesthetic made a drastic shift to films like Old Joy (2006) and Wendy and Lucy (2008)—quieter, less obvious films rooted in a pensive style. Watching her freshman effort today, its story and formal approach feel far removed from the writer-director’s later titles. Rather than her muted but loaded scenes and protracted sequences of weighted silence, her style has a playful, distinctly 1990s manner here. Its most apparent influences remain Terrence Malick’s first two films, Badlands (1973) and Days of Heaven (1978), in its use of stream of consciousness narration and concentration on understated moments and observations in Nature, but particularly the former film in its lovers-on-the-run scenario. However unlike Reichardt’s later films River of Grass may be, it nonetheless contains her concentration on the experiences and internal lives of workaday characters.

Being a Reichardt film, it’s a carefully observed work that layers characters in opposition to mainstream styles, even though it resembles a familiar cinematic archetype. River of Grass adopts a story structure eternalized by Fritz Lang’s You Only Live Once (1937) and Nicholas Ray’s They Live by Night (1948), early features about two young misfits who break the law and evade the police on the road. The 1990s featured a resurgence of such films—many of them riffing on Badlands and Bonnie and Clyde (1968)—including David Lynch’s Wild at Heart (1990), Tony Scott’s True Romance (1993), and Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers (1994). Reichardt uses this popular trend in American cinema and subverts it, embracing the predictable crime genre of her contemporaries to touch on the unsentimental realism for which she would later be known. Her approach is highly stylized, however, far more apparently so than any of her subsequent films. And it’s a style inflected with the poetic observations and idiosyncrasies of both early Malick and popular trends in early 1990s independent cinema.

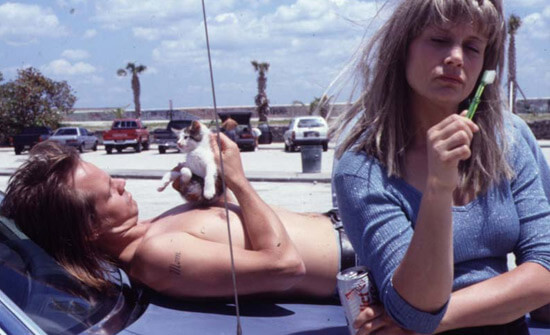

River of Grass takes place in Dade County, Florida, near Reichardt’s home town of Miami. The film tells the story of Cozy (Lisa Bowman, in her only screen role), a housewife who feels no affection for her two children and no love for her high-school sweetheart husband. In her voice-over (clearly informed by Sissy Spacek’s narration in Badlands), Cozy explains that her mother ran away to join the circus, and her home was previously owned by a woman who chopped up her husband—two details that seem to be on her mind. One night, she leaves the kids at home and walks to a local bar, where she meets Lee (Larry Fessenden), a stringy layabout with no prospects. “I’m kind of in limbo right now,” Lee says of his employment situation. “Limbo,” echoes Cozy, stifled by the domesticated direction of her life, “that sounds nice.” At the same time, Reichardt tells the story of Cozy’s father, Jimmy (Dick Russell), a veteran detective and jazz drummer who desperately tries to find his lost sidearm, which, unbeknownst to Cozy, happens to be in Lee’s possession. After the bar, Lee and Cozy break into a backyard pool area for a swim. At the very moment Lee shows Cozy the gun, the owner investigates the noise, and the gun goes off, leaving Lee and Cozy to believe they’ve killed someone.

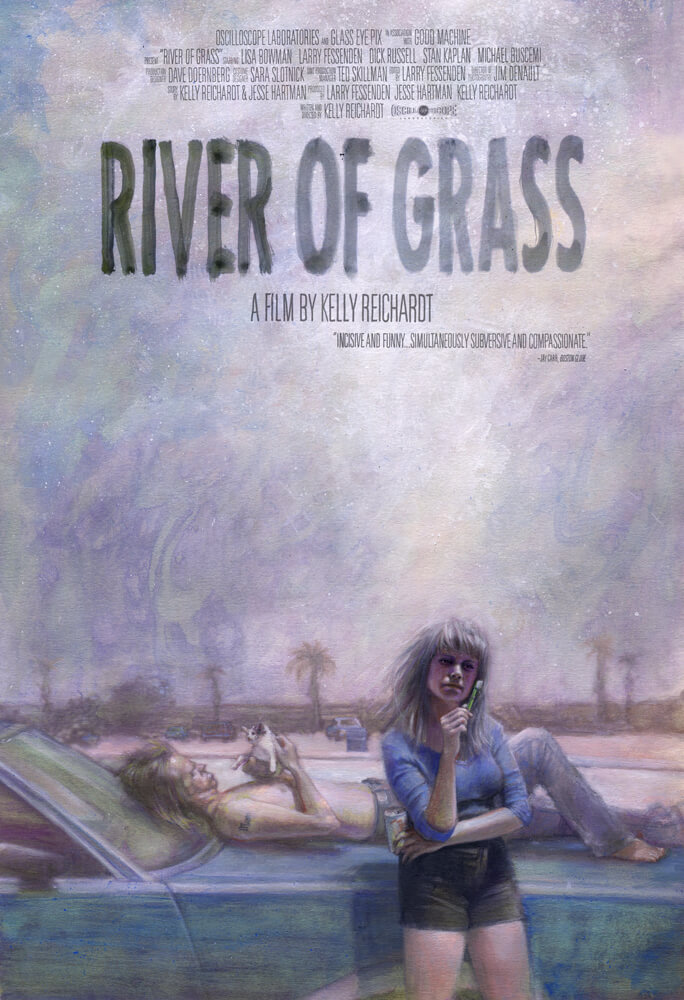

What proceeds may initially resemble a brand of 1990s crime film (complete with the poster’s tagline, “A girl, a gun, and nowhere to go.”), but Reichardt’s deviations remain crucial to appreciating how she undermines the genre. At first, Lee and Cozy hole-up in a cheap motel, evading the authorities. They steal Lee’s mother’s record collection to sell for cash, planning to leave Miami to get across the state line; however, they’re destined never to leave the Everglades of the title. Reichardt reveals that Lee and Cozy have not killed anyone and that only Jimmy, who wants to recover his lost gun and bring his daughter home, pursues them. In this sense, Reichardt disrupts the usual trajectory of these stories. Watch how Lee’s attempted convenience store robbery is undercut by another armed robber, or how the couple’s eventual escape from Miami is undone by the most mundane of roadblocks, a twenty-five-cent toll they cannot pay. At every turn, Reichardt does something at odds with the traditional setup. But even as the story begins to take a shift toward a predictably down-turned version of the lovers-on-the-run setup, as Cozy and Lee must return to Dade County for their lack of funds, Reichardt shocks with her ending: Lee proposes they settle down together, that they find jobs to afford an apartment—the very thing from which Cozy wanted to escape—and she responds by shooting him and tossing his body out of the moving car.

Reichardt matches the story’s unconventional turns with a similar playfulness of style, reminiscent of the 1990’s obsession with pastiches that both imitate and alter known models. River of Grass opens with diegetic jazz band music with a fast tempo over the credits. As the story unfolds, it does so with single-digit title cards that denote chapters, a commonplace structural device in the indie cinema of the era, most often attributed to Quentin Tarantino. At times, River of Grass even looks like Kevin Smith’s Clerks, another film that debuted at Sundance in 1994: When Lee and his friend investigate the roadside spot where Jimmy lost his gun, the tableau shot recalls Jay and Silent Bob standing in front of the Quick Stop. Elsewhere, Reichardt uses form to create humor, evidenced in certain cuts and zooms, such as the moment Reichardt zooms out to reveal Lee sleeping naked on his bed, while his grandmother opens the blinds and sits next to him.

Fessenden edited the picture, marking one of the only times Reichardt did not serve as editor of her own footage, and the result is snappier than her later work. Note the interlude sequence in which Jimmy’s jazz drums play over an inter-cutting between the film’s various converging characters, family photos, and Cozy’s father’s tossed apartment. Similarly, the film displays an amateurish use of inserts that draw attention to basic actions and random images—a hand in a till, a wildflower, a crack in a house teeming with ants—and these are cuts unique within Reichardt’s otherwise habitual use of medium and wide shots. Fessenden and Reichardt also piece together cutaways that reflect Cozy’s narration, as when she thinks about her mother in black-and-white photographs or imagines of her home’s previous owner chopping up her husband in a bloody horror image. And though some of Bowman’s characteristically flat narration channels the aching ennui of the prematurely domesticated twentysomething—she says, “I’ve heard it said the mother-child bond begins at birth, but for me, this never occurred,” as she prepares a bottle of Coca Cola for her infant—it occasionally resorts to hackneyed remarks such as Cozy’s observation that “murder was thicker than marriage.”

These formal flourishes contain many of the calling cards of 1990s cinema, just as Reichardt’s screenplay has a penchant for cute coincidences and happenstance prevalent in the era’s output, such as Mystery Train (1989), Twenty Bucks (1993), and Pulp Fiction (1994). At one point, Lee crosses paths with Jimmy in a used record shop, though the two remain oblivious to each other—recalling when Butch and Vincent Vega cross paths in the bar in Pulp Fiction. Later, after she kills Lee, Cozy tosses her father’s gun out of the car window, and it lands in the exact spot where Lee’s friend initially found it. As the story creates a sense of playful irony, these connections do less to reinforce a grandiose meaning than engage the audience in Reichardt’s unconventional mode of storytelling. Part of what defined independent cinema of the 1990s was how it deviated from the expected so that the audience could recognize and celebrate its deviations. River of Grass finds Reichardt at her most formally playful, even if that quality finds her conforming to the period’s modes of indieness.

These formal flourishes contain many of the calling cards of 1990s cinema, just as Reichardt’s screenplay has a penchant for cute coincidences and happenstance prevalent in the era’s output, such as Mystery Train (1989), Twenty Bucks (1993), and Pulp Fiction (1994). At one point, Lee crosses paths with Jimmy in a used record shop, though the two remain oblivious to each other—recalling when Butch and Vincent Vega cross paths in the bar in Pulp Fiction. Later, after she kills Lee, Cozy tosses her father’s gun out of the car window, and it lands in the exact spot where Lee’s friend initially found it. As the story creates a sense of playful irony, these connections do less to reinforce a grandiose meaning than engage the audience in Reichardt’s unconventional mode of storytelling. Part of what defined independent cinema of the 1990s was how it deviated from the expected so that the audience could recognize and celebrate its deviations. River of Grass finds Reichardt at her most formally playful, even if that quality finds her conforming to the period’s modes of indieness.

Despite the stereotypically 1990s uses of form and storytelling devices found throughout River of Grass, the film fits nicely into Reichardt’s oeuvre in terms of theme. From the beginning, Reichardt has told stories about characters determined to escape their present situation, even though they remain unable to move forward or make progress. Such stuck characters can be found in Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, Meek’s Cutoff (2010), Night Moves (2013), and Certain Women (2016)—films often centered on working-class individuals or outsiders of traditional society that try to make their own way. Reichardt’s continued interest in the leisurely paced rhythms of everyday life, in all its associated anxieties and disquietness, has been there from the start. It’s never more apparent than the perfect image of Cozy, who, having left her children and husband, floats in a stranger’s pool, aimlessly treading water, yet feeling entirely free of all worldly obligation, if only for the briefest of moments. It’s an image countered by the last shot of Cozy, having killed her would-be co-criminal, stuck in traffic.

Bibliography:

Fusco, Katherine, and Nicole Seymour. Kelly Reichardt – Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Hall, E. Dawn. ReFocus: The Films of Kelly Reichardt. Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review