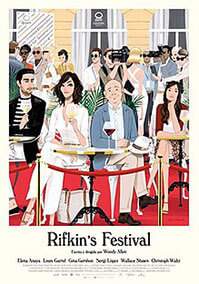

Rifkin’s Festival

By Brian Eggert |

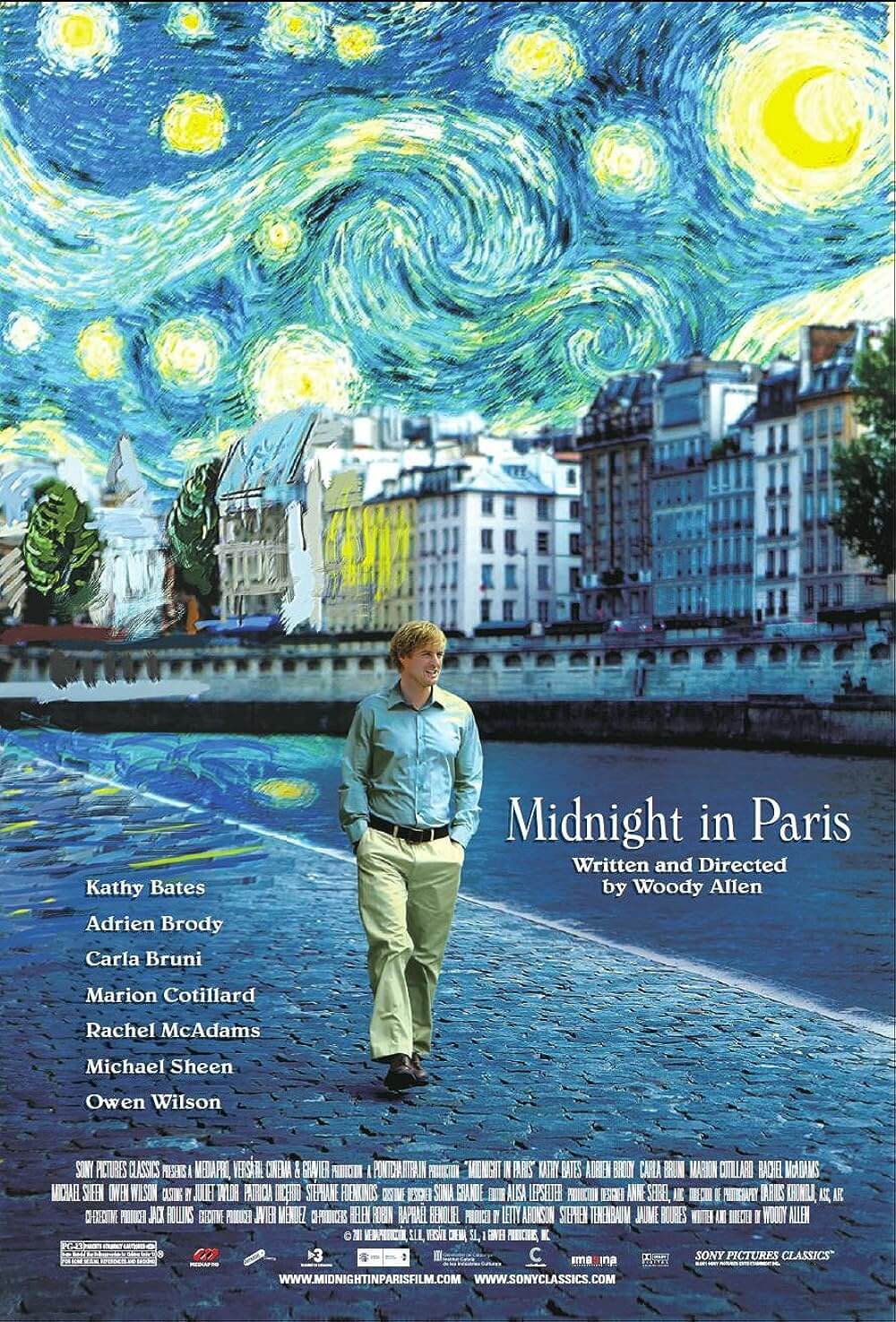

Rifkin’s Festival continues Woody Allen’s recent string of minor work. The writer-director’s 49th feature in a half-century of filmmaking boasts a few memorable one-liners and a touch of fantasy—qualities often associated with his best output. But it doesn’t crackle like so many of his earlier films, nor even those from a decade ago. The scenario has the potential to transport the viewer into another world, like Midnight in Paris (2011) did. Instead, it plays in that flatly competent manner of his recent fare: Café Society (2016), Wonder Wheel (2017), and A Rainy Day in New York (2020). The unfussy result does little more than go through the motions, despite the occasional wisecrack that feels like it’s been sitting in Allen’s famous drawer of unused gags since 1975. Take the moment when, in a dream, someone asks Mort Rifkin (Wallace Shawn), another of Allen’s self-deprecating onscreen counterparts, what he would do if he met God. Mort replies, “After what God’s done, I’d have nothing to say to him. Let him talk to my lawyer.”

Infrequent comic pearls aside, the story unfolds against the backdrop of the San Sebastián International Film Festival. That’s where Allen shot and debuted the film back in 2020. But, given the controversy around the director in recent years, it’s taken some time for his latest to secure US distribution. Unceremoniously dropped into limited release and VOD by MPI Media Group, Rifkin’s Festival has a cast of lesser names, signaling Allen’s current struggle to find top-tier performers to appear in his work. His last film boasted A-listers. Rifkin’s Festival features Steve Guttenberg. Still, the film makes excellent use of San Sebastián exteriors and several Spanish actors, captured in cinematographer Vittorio Storaro’s stunningly orange and borderline surreal use of sunsets. And since the proceedings feature plenty of film references embedded into the dialogue, the film-savvy viewer will likely derive some knowing pleasure from the conversation. It’s not enough to leave a lasting impression, though.

Shawn is well-cast as Mort, a New York intellectual and former film professor. Mort attends SIFF with his publicist wife, Sue, played by Gina Gershon, who reminds us that she’s capable of more than her recent filmography suggests. Mort has settled into a stodgy existence, believing that European art cinema represents the height of the art form, and everything else is low- and middle-brow by comparison. “Your hostility is starting to show,” Sue warns him. She’s there representing a famous young director, Philippe (Louis Garrel), whose latest film, Apocalyptic Dreams, explores the cliché “war is hell”—and Philippe promises his next picture will resolve tensions in the Middle East. Sour on the pretentious Philippe and anything new, Mort (Latin for death) has become a hypochondriacal old fuddy-duddy, and Sue has started to notice. Mort watches as the mutual flirtations between his wife and Philippe intensify over the 10-day festival. Meanwhile, he works through his anxieties about his marriage, looming irrelevancy, and mortality through cinematic contexts.

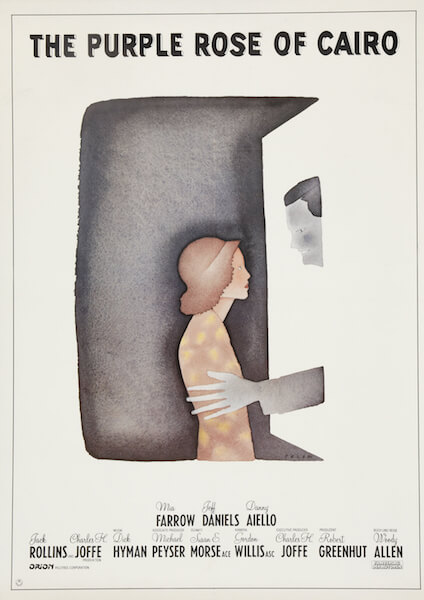

An ode to celluloid dreams, Rifkin’s Festival loses itself in convincingly recreated scenes from Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963), François Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1963), Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), and many others. Mort slips away into black-and-white reveries, captured by Storaro in the Academy ratio and mounted by production designer Alain Bainée with convincing attention to detail. Allen hasn’t been this romantic about cinema since The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985). Less romantic is a subplot involving Mort’s visits to see a Spanish doctor, Jo (Elena Anaya), about his heart. Besides her beauty, Jo once lived in New York and likes classic movies, so she naturally piques Mort’s interest. She’s also unhappily married to a philandering artist—a shadow of Javier Bardem’s volatile painter in Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2009). While his wife carries on a barely concealed affair with her client, Mort hopes for fireworks with his doctor. Fortunately, Allen spares us the awkward coupling, even while reminding us that love and art make life’s trials and tribulations worthwhile—a lesson that’s not only commonplace but not unique to Allen’s filmography.

An ode to celluloid dreams, Rifkin’s Festival loses itself in convincingly recreated scenes from Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963), François Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1963), Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), and many others. Mort slips away into black-and-white reveries, captured by Storaro in the Academy ratio and mounted by production designer Alain Bainée with convincing attention to detail. Allen hasn’t been this romantic about cinema since The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985). Less romantic is a subplot involving Mort’s visits to see a Spanish doctor, Jo (Elena Anaya), about his heart. Besides her beauty, Jo once lived in New York and likes classic movies, so she naturally piques Mort’s interest. She’s also unhappily married to a philandering artist—a shadow of Javier Bardem’s volatile painter in Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2009). While his wife carries on a barely concealed affair with her client, Mort hopes for fireworks with his doctor. Fortunately, Allen spares us the awkward coupling, even while reminding us that love and art make life’s trials and tribulations worthwhile—a lesson that’s not only commonplace but not unique to Allen’s filmography.

Having appeared in many Allen films, Shawn makes a great Allen avatar. But the movie is missing something. Whether it’s the actor or director’s failure to achieve the intended comic timing, the film would have benefitted from an amplified tempo. As is, Rifkin’s Festival feels like an older man’s comedy, which isn’t necessarily bad unless the humor would be more effective if delivered at a snappier cadence. Shawn moves a little slower now, just as Allen seems to be running out of steam. The occasional touch of greatness in the director’s Blue Jasmine (2013) or woefully underrated Irrational Man (2015) comes from a combination of his best writing and performers capable of elevating the material. In Rifkin’s Festival, Gershon and Garrel manage a few well-honed moments, but otherwise, the proceedings reveal that Allen isn’t what he used to be. Of course, few filmmakers have continued to produce new material into their mid-80s. But when the 84-year-old Ridley Scott is still experimenting with the energy of a budding filmmaker, making features that feel vital and alive, one can only hope that Allen will find a similar late-career resurgence.

Rifkin’s Festival isn’t entirely forgettable. Allen manages some inspired gags, including one involving Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) and a sled called “Rose Budnick,” which shares the name of a Holocaust survivor. The aforementioned Guttenberg also appears in a parody of Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel (1962). These flights of fancy keep the viewer distracted from the low-key stakes and appeal, following Shawn as Mort wanders about the gorgeous scenery, complaining that his finger hurts. Allen evidently recognizes his old-manisms and pokes fun at himself, but not with any great dimension. In the end, Allen resorts to his oft-used device of a summary montage—see Annie Hall (1977)—that recaps some of the film’s highlights, here dedicated to Mort’s cinematic fantasies. Unfortunately, the trick doesn’t carry the weight it once did, mostly because Allen hasn’t compelled much interest beyond the occasional quip or classic movie reference. Here’s hoping that, if he makes a fiftieth, it leaves more of an impression.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review