Ricki and the Flash

By Brian Eggert |

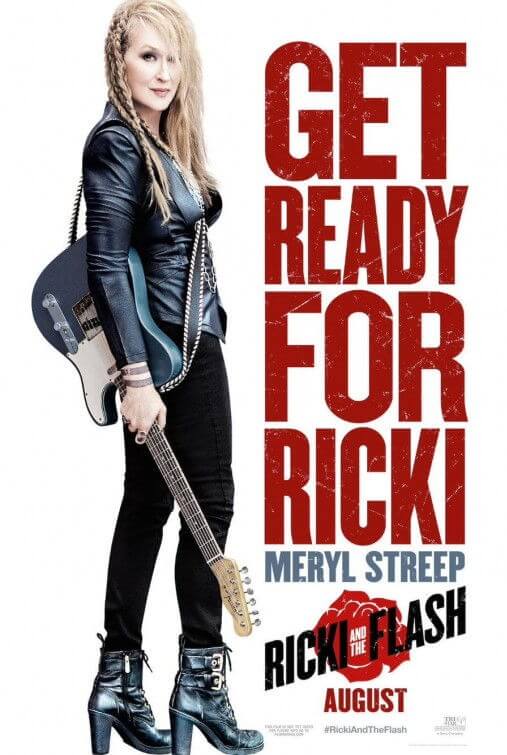

From screenwriter Diablo Cody comes Ricki and the Flash, another story of a self-made, independent woman with a rebellious streak. In any other writer’s hands, that concept sounds exciting. But overcooked per usual, Cody’s script represents an unapologetic character who’s admirable from a distance, though you would never want someone like Ricki in your life. Meryl Streep plays the titular singer, the middle-aged voice of a San Fernando Valley cover band, the Flash. The character affords Streep the opportunity to sing once more, and she has a beautiful voice, demonstrated on A Prairie Home Companion (2006), Mamma Mia! (2008), and Into the Woods (2014). She even learned to play guitar for the role. Along with an original song or two (“Cold One” is particularly affecting), the soundtrack is worth a download. But Cody and her characters have more esteem for this complicated character than the audience, and she never quite convinces us that Ricki is worth the complete redemption she receives.

Alongside three seasoned pros (Bernie Worrell, Joe Vitale, and Rick Rosas) and her lead guitarist/boyfriend Greg (Rick Springfield—yes, the Rick Springfield), Ricki Rendazzo, formerly known as Linda Brummell, left her husband and three children back in Indianapolis years ago to pursue her career in music. With her eighties hair, dark eye makeup, and black leather duds, this middle-aged wannabe-rocker holds onto the dream and won’t let go. Cody based the character on her mother-in-law, and it’s just the kind of character this screenwriter would find redeeming. After all, Cody wrote Jennifer’s Body and Young Adult, two films about horrible people who are meant to be complicated, destructive, and funny. Like those characters, as well as the more endearing protagonist played by Ellen Page in Juno, Ricki offers no apologies for her bad behavior.

Working as a supermarket cashier to support herself—because playing with the Flash in local bars isn’t paying the bills—Ricki’s life isn’t quite the rocker fairy tale she wanted it to become. When her tidy and sensitive ex-husband Pete (Kevin Kline) calls to explain their daughter Julie (Mamie Gummer, Streep’s real-life daughter) is depressed, she’s shocked to discover Julie tried to commit suicide. Julie is hopeless because her husband left her for another woman. But Ricki returns to Pete’s mini-mansion and heals some old wounds with a makeover for Julie and some no-nonsense sass. Pete and Julie seem to welcome Ricki back into their lives, albeit temporarily, but not everyone is so forgiving; her two sons (played by Sebastian Stan and Nick Westrate) want nothing to do with her. And Pete’s longtime wife, the woman of color who raised Ricki’s children while she was off pursuing her dream, is played by Audra McDonald with absolute confidence, and she’s the one person who puts Ricki in her place. Their confrontation brings to the forefront Ricki’s petty attitude, issues with race among them.

Cody has written Ricki with a wealth of contradictions that make her interesting. She claims her family is so important to her, but she’d rather live alone in a dank L.A. apartment and see them every few years. She claims to be freewheeling and independent, yet she voted for George W. Bush and has a Tea Party logo tattooed on her back. But these contradictions are narrowly addressed, just as the potential powder keg of conflict between Ricki and her family never comes to a believable head. Quite the opposite. By the final scenes, Cody’s assemblage of supporting character types and paper-thin characterizations all come to love Ricki, flaws and all, as unapologetically as she’s been forced down the audience’s collective throat. None of the scenes leading up to this revelation are emotionally believable or stick with the audience, perhaps because Cody has failed to communicate what, besides music, makes Ricki tick.

Maybe music is all Ricki needs. Some people can live through the embrace of a particular artform. Certainly, this is why director Jonathan Demme was attracted to the material; he’s delivered some of the best concert docs with the Talkingheads’ Stop Making Sense (1984) and several with Neil Young. In a way, Ricki Rendazzo made this critic think of Vincent Van Gogh—a mess-of-a-human-being whose art was unappreciated in its time. Except, Ricki and the Flash doesn’t dwell on the artform itself or even Ricki’s love of music—music is a side note in a cliché dramedy about an estranged mother making amends with her family. But she doesn’t really make amends so much as wait for her family to accept her, which they do at her son’s wedding finale where, being typical Ricki, she makes the moment all about herself. If not for Streep’s presence in the role, Ricki and the Flash might be a contemptible film, but alongside Kline and Gummer’s strong performances, the film is bearable, if devoid of any real conflict or relatable emotions.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review