Revolutionary Road

By Brian Eggert |

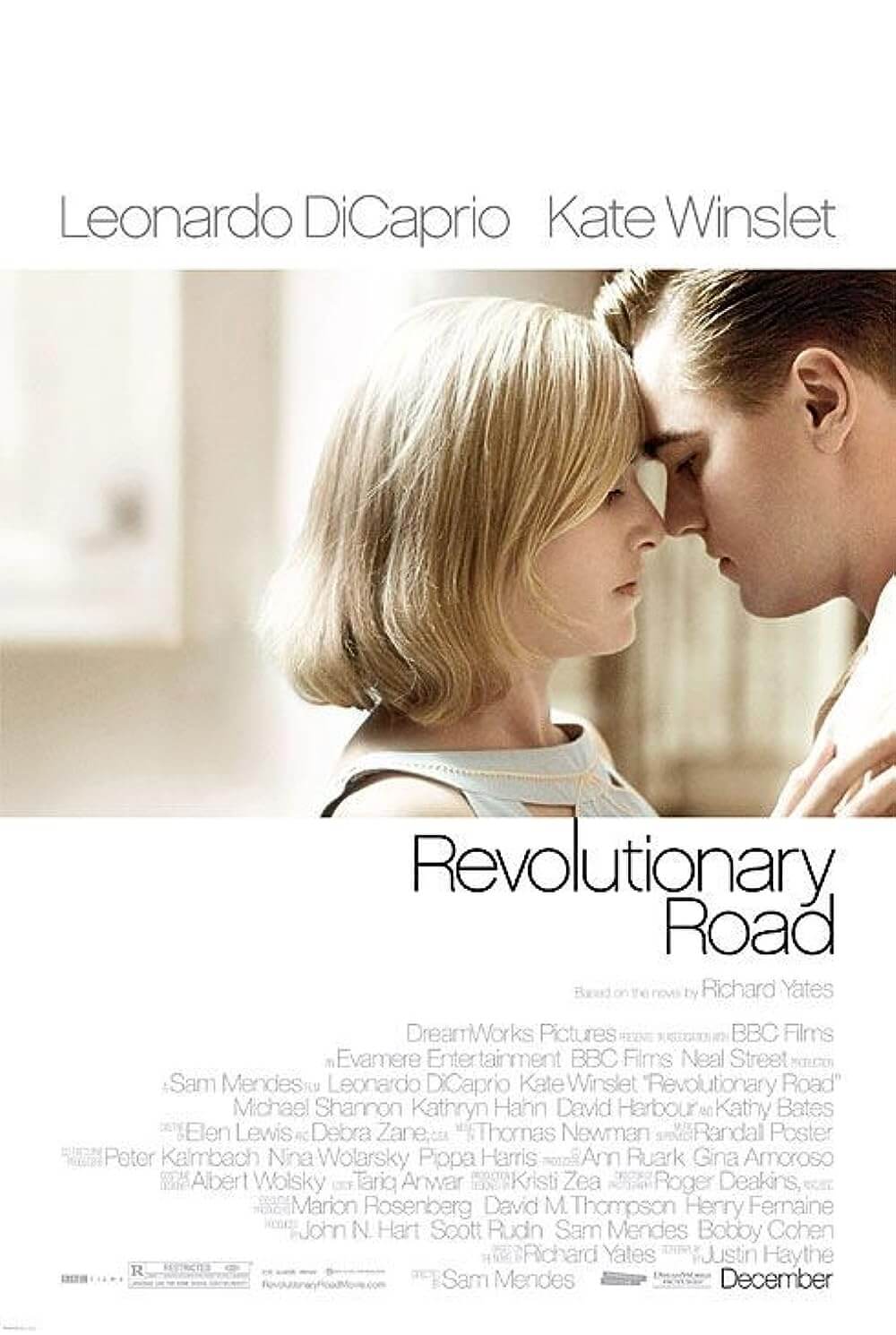

From the outset, Revolutionary Road regards the ideal American lifestyle in suburbia as a small nightmare from which there is no escape. Based on the fatalistic 1962 novel by Richard Yates, this deeply upsetting tale of 1950s conformity acknowledges how the spirit that birthed America is no longer a pregnant womb ripe with potential. Instead, this beautifully shot and brilliantly acted picture suggests our romanticized design for the happy homestead is a diseased security blanket. Addressing the dissatisfaction of their routine lifestyle within the first scenes, the film examines the marriage of Frank and April Wheeler, played to perfection by Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet. They’re homeowners in Connecticut’s sleepy community on Revolutionary Road, a stretch that, according to their real estate agent Mrs. Helen Givings (Kathy Bates), is for better people. All their neighbors regard them as special, a perfect couple blessed with two children, a fine home, and a happy existence. Indeed, they’re playing their parts nicely.

Sam Mendes directs the film, with cinematographer Roger Deakins (Doubt, No Country for Old Men) shooting in marvelously prosaic tones, sentimentalizing the images as if deriving them from a Norman Rockwell painting. The visual setup aligns with model depictions of American life, structuring white houses strewn with red shutters, husbands off to work in suits and hats, women in dresses preparing meals, drinks on the rocks, countless cigarettes smoked, and the utter banality of it all. The Wheelers don’t want this humdrum way of living, however envied by their neighbors. Marked by the patterns of suburbia, their daily grind has become fixed to claustrophobic extremes, with Frank working in the same sales office as his ever-unsuccessful father used to, and April, once with aspirations to be an actress, resigned to being a homemaker and mother of two.

Suddenly, April proposes a change: They could use their savings and money from selling their house to move to Paris so Frank can find himself. April will work as a secretary in a government office and support the family; Frank will spend this time discovering what will truly make him happy. What a selfless and moving proposal from April, offering such an accessible realization of true happiness. The prospect itself is a vision. Frank excitedly agrees and they begin telling friends, buying boat tickets to Europe, arranging everything for their new lifestyle. All of a sudden their lives have purpose. Those Wheelers are being childish, the neighbors say, as they weep with frightened jealousy that they too might be so bold.

One afternoon, Mrs. Givings asks if she might introduce the Wheelers to her son John (Michael Shannon), an intellectual who’s been recovering from mental collapse. She thinks them the most interesting couple she knows, thus having more appeal for a person in John’s state. His condition consists of simply telling the truth, calling out what resides behind the façade of social masking. And though John is at first skeptical of them, he finds the Wheelers’ plans for social elopement inspiring—how rare that they see through the fabrication of suburbia and desire escape from the prison every other “normal” person accepts as regularity. And though John is considered crazy on his parents’ terms, for the Wheelers, John’s understanding makes him the sanest person they know.

As the film progresses, however, the prospect of leaving the safety net of his patterns becomes too much for Frank. Hints are dropped that perhaps they shouldn’t go, including an offer for a promotion, meaning more money and a better style of living. Why go to Paris, after all? Isn’t it possible to be happy in America? For April, there is no question that staying means a blind acceptance of and clinging to the social safety net that the world has provided for them. She wants to live, and living in their home, playing house, pretending to be happy is a deception. In one of their many intense confrontations, she admits she couldn’t delude herself and stay: The truth is always there, she points out; people just get better at lying to themselves.

Flawlessly presenting the Wheelers’ every feeling, from subtle concealment to their desperate, raging blasts of constrained yearning, DiCaprio and Winslet have rarely been better. They starred together in Titanic, of course, but look how far both have come. Each has evolved from a sex symbol and pop-culture icon into a daring performer whose range is incomparable for today’s actors. With titles like The Aviator, Little Children, The Departed, and The Reader to their names, placing them together again now makes for an uncanny display of talent both should be commended and awarded for. Their performances are simply outstanding.

Mendes handled familiar territory when directing American Beauty. But where that film satirizes and nearly lampoons with darkly humorist overtones, reducing itself almost to a farce, Revolutionary Road excels with dramatic potency, hearty symbolism, and biting relativity. Mendes doesn’t wink through the camera with every scathing comment about the dullness of suburbia; rather, he allows the drama to progress naturally, structuring messages both about 1950s societal expectations and the more transcendent meaning to American identity.

Certainly the film can be read as just a grave character study, and even more so as an allegory for the defeatist nature of resigning oneself to a 1950s’ brand of societal expectation and domesticated subsistence. Yates’ truly profound indictment dwells in the story’s suggestion that the American spirit that once rebelled against the orthodoxy of England to stake its claim in the world has died in today’s American family. Our Revolutionary Road is now paved with freshly groomed lawns and shiny new automobiles. Getting by is often good enough: Living life versus fighting for it; relaxing in our homes instead of discovering something new and meaningful in the unknown. When Manifest Destiny fulfilled itself, what other frontier was there? Yates doesn’t know, but he asks if there’s anything better than this.

The film questions if the American Dream was ever worth dreaming about, by dissecting the perfect marriage with rising anticipation and crushing its possibility with exceptionally unforgiving emotional bombshells. The lasting effect of Revolutionary Road remains painfully true and dramatically devastating, retaining its harsh and hopeless sense of numbing censure against the unhappy lives of the ordinary. Audiences will find self-examination unavoidable and crucial after viewing.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review