Return to Seoul

By Brian Eggert |

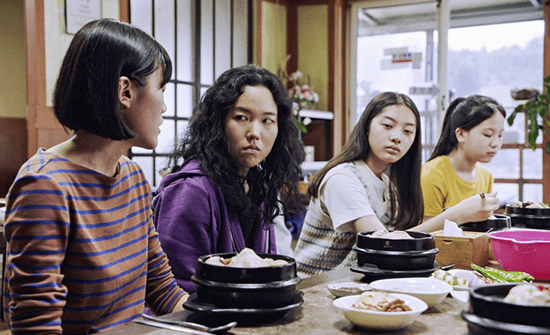

Return to Seoul follows a restless search for identity. First-time actor Park Ji-min plays an unpredictable 25-year-old Frenchwoman, Frédérique Benoît, who goes by Freddie. Born in South Korea but adopted and raised in France, Freddie makes the impromptu decision to buy a ticket to her birthplace. She has no plan, doesn’t speak the language, isn’t versed in Korean culture, and has no idea how to contact her biological parents. But after arriving, she quickly makes some friends at a restaurant over a few bottles of soju, yet she refuses to follow their local custom of pouring for others. After a while, everyone’s a little drunk, and they observe her “pure” Korean features. She doesn’t know what that means and doesn’t feel “pure”—more like an outsider. In a telling admission, Freddie notes that she plays piano and explains sight reading to the group, how the player must “evaluate the danger and jump in.” It becomes apparent that the whole scene at the bar encapsulates her attitude toward life. She improvises from one moment to the next and defies any standard thrust upon her. She doesn’t feel that she belongs, so why should she conform? Still, there’s a nagging sense of needing to feel whole, even if she doesn’t want to admit as much.

Deploying an episodic structure that unfolds over eight years while Freddie searches for some semblance of an identity, Return to Seoul’s writer-director David Chou could no doubt relate to her sense of dislocation. Born in France, Chou is the grandson of Norodom Sihanouk, a Cambodian filmmaker whose prolific work in the 1950s represented the country’s only cinematic output. His grandfather paved the way for more Cambodian cinema throughout the 1960s until his mysterious disappearance in 1969. But much of his work remains lost or forgotten since the Khmer Rouge regime took control in 1975 and dismantled the national film industry for the duration of their four-year rule. Chou, whose family emigrated to France, learned of his grandfather’s legacy in adolescence and resolved to follow his example to become a filmmaker. After making shorts and documentaries, he debuted his first feature-length drama with 2019’s Diamond Island. The idea for his second drama, Return to Seoul, came about after helping a friend through a similar experience as Freddie. The result confronts the unanswerable questions and “what if” scenarios after adoption. So it’s perhaps telling that the film played at the Cannes Film Festival in the Un Certain Regard section under the title All the People I’ll Never Be.

Immediately upon arriving, Freddie finds a translator in Tena (Guka Han), who encourages her to visit the Hammond Adoption Center. They look over Hammond’s literature and note the recent decline in adoptions, which reached its height in the decades after the Korean War. However, the last three decades have seen a decrease in adoptions, given the country’s economic stability. Downturn notwithstanding, Freddie learns the process by which South Korean adoptees can reconnect with their birth family is backwards. The process involves Hammond sending the biological parents a telegram, informing them the child they gave up wants to get in contact. If the parent replies, Hammond will arrange and oversee an initial meeting. Freddie also learns that her birth name was Yeon-hee, meaning “docile and joyful,” two adjectives that couldn’t be further from describing her accurately. But might she have been docile and joyful had she been raised under different circumstances? These impossible-to-answer questions leave Freddie feeling unresolved.

Although there’s no response from Freddie’s mother, it doesn’t take long to hear back from her father (Oh Kwang-rok), who’s just a car ride away. Joined by Tena, Freddie suddenly announces on the way there that she wants to go back—an outburst she claims is a joke, though it might have been a natural reflex to the situation. She remains uncertain about what this relationship with her biological father should mean, if anything, and when she finally meets him, the initial encounter is made worse by language barriers, awkwardly polite interactions, and her father’s latent insistence on paternal behavior—he wants to buy her shoes and arrange for her to marry a Korean man. Worse, she’s taken aback by his self-punishing regret over putting her up for adoption, even though he’s since started another life. After spending a couple of days with him and his family, Freddie finds her phone barraged with drunken voicemails and persistent texts—she learns it’s characteristic of Korean men to spew their sorrows in sloppy displays. But it’s all too much for her.

Although there’s no response from Freddie’s mother, it doesn’t take long to hear back from her father (Oh Kwang-rok), who’s just a car ride away. Joined by Tena, Freddie suddenly announces on the way there that she wants to go back—an outburst she claims is a joke, though it might have been a natural reflex to the situation. She remains uncertain about what this relationship with her biological father should mean, if anything, and when she finally meets him, the initial encounter is made worse by language barriers, awkwardly polite interactions, and her father’s latent insistence on paternal behavior—he wants to buy her shoes and arrange for her to marry a Korean man. Worse, she’s taken aback by his self-punishing regret over putting her up for adoption, even though he’s since started another life. After spending a couple of days with him and his family, Freddie finds her phone barraged with drunken voicemails and persistent texts—she learns it’s characteristic of Korean men to spew their sorrows in sloppy displays. But it’s all too much for her.

More affected by her adoption than she’s willing to admit, Freddie remains in a state of irresolution given her birth mother’s unresponsiveness. Return to Seoul finds the protagonist drifting from one experience to the next, one impermanent relationship to the next. In a single night, she rebuffs an earnest, sensitive one-night stand (Kim Dong-Seok) and instead makes a sudden pass at Tena, who tells her, “You’re a very sad person.” Then she encounters her father and tells him she never wants to see him again. The film leaps to two years later, when Freddie lives with a tattooist (Lim Cheol-Hyun) and goes through a phase of numbing herself with alcohol and psychedelics. Still, she wonders every birthday, “Is my mother thinking about me?” She finds out when Hammond explains that her mother responded and said she didn’t want to see her. Then, five years later, Freddie finds herself working for an older international arms dealer (Louis-Do de Lencquesaing), serving as a “Trojan Horse” for a French company to appeal to Korean missile buyers. She returns to South Korea with her boyfriend, Maxime (Yoann Zimmer), but warns him that the country is “toxic” for her—a reality that becomes apparent when, after a lunch with her father, who’s improved his desperate behavior since last they met, she warns Maxime, “I could wipe you from my life with the snap of a finger.”

Having that knowledge—that she has control over her relationships with men, and that she can reset her life whenever she chooses—becomes a manner of protecting herself from the impermanence of life. Park brilliantly captures Freddie’s state of flux, shifting identities and personalities while simultaneously yearning for some measure of stability. Whenever she finds herself in a comfortable groove, she’s reminded that some part of her past remains open-ended and unanswerable. And yet, even if an answer presented itself, she may reject it. Freddie is cagey and evasive, unsure if she’s French or Korean, and unwilling to acknowledge how much she needs to understand the equation. Whether she’s waking up in an alley or drunk dancing to distract herself, these questions remain on Freddie’s mind. Accordingly, Park’s performance switches from self-destructive to stone-faced in an instant, making Freddie a fascinating, alluring, yet frustrating mystery to most who encounter her.

Chou’s direction and writing refuse to supply easy answers for Freddie or the viewer, and the filmmaking shifts along with the character’s state, always keeping the audience at a slight remove. There are no dramatic revelations or resolutions in Return to Seoul, and director of photography Thomas Favel approaches the visual poetry of Christopher Doyle’s work with Wong Kar-wai to evoke this. Freddie’s unspoken feelings and spontaneous choices find Favel’s camera transitioning from her neon-shimmering nightlife to quiet pastoral scenes with equal beauty and restraint. Like Freddie, Favel’s images change their mood impulsively; however, they always feel part of the same aesthetic. The music by Jérémie Arcache and Christophe Musset is just as unpredictable, blending electronic sounds with heavy percussion and hypnotic tones, depending on the scene. Chou’s style shifts slightly in the final scenes to a misty European countryside, where Freddie seems to have found some peace in the morning light and rolling hills, only to realize she hasn’t.

Chou’s direction and writing refuse to supply easy answers for Freddie or the viewer, and the filmmaking shifts along with the character’s state, always keeping the audience at a slight remove. There are no dramatic revelations or resolutions in Return to Seoul, and director of photography Thomas Favel approaches the visual poetry of Christopher Doyle’s work with Wong Kar-wai to evoke this. Freddie’s unspoken feelings and spontaneous choices find Favel’s camera transitioning from her neon-shimmering nightlife to quiet pastoral scenes with equal beauty and restraint. Like Freddie, Favel’s images change their mood impulsively; however, they always feel part of the same aesthetic. The music by Jérémie Arcache and Christophe Musset is just as unpredictable, blending electronic sounds with heavy percussion and hypnotic tones, depending on the scene. Chou’s style shifts slightly in the final scenes to a misty European countryside, where Freddie seems to have found some peace in the morning light and rolling hills, only to realize she hasn’t.

Chou and Park achieve something rather overwhelming in Return to Seoul, creating a film that feels whole even though its main character is not. Freddie changes many times throughout, yet the film always remains cohesive. Instead, the viewer feels the absence and many contradictions inside her, even after reconnecting with her mother. The aching message Freddie receives when she attempts to send an email—“Address Not Found”—echoes the difference between real life and the movies, while also doubling as a label for Freddie. There are no happily ever afters or fairy-tale conclusions in life, and the rootless Freddie will never attain that measure of closure. Instead, people grow and change. They meet new lovers, switch careers, and try new diets—Freddie more than most. This constant evolution becomes symptomatic of an unending, even tragic search for self, ever wandering to find out what feels right, if anything. Propelled by melancholy and the unresolvable inner tension of its main character, Return to Seoul is one of 2022’s best films. It flows from one wistful chapter to another in Freddie’s life, but the stops along the way feel less significant than the film’s overall portrait of her tender, futile quest for identity.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review