Resident Evil

By Brian Eggert |

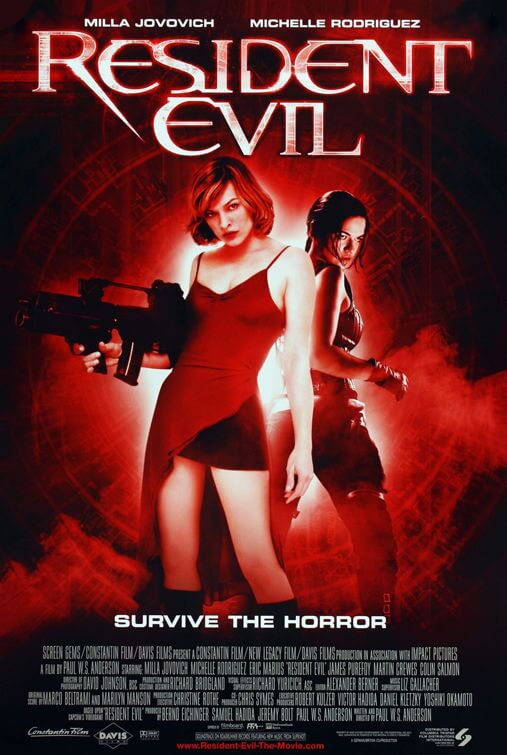

Released on the Sony Playstation in 1996, the game Resident Evil sold in huge numbers and spawned several sequels on multiple platforms. Centered on puzzle-solving and zombie killing, the survival horror game follows investigators into a viral outbreak. As the story goes, the Umbrella Corporation, a huge multinational conglomerate, does research into a “T-virus” for god-knows-what reasons. The virus gets loose, and its victims become the walking undead. The movie adaptation was released in 2002. And if you’re watching a movie based on a video game, chances are writer-director Paul W. S. Anderson directed it. He made Mortal Kombat and Alien vs. Predator (not to mention Event Horizon and Soldier, which may as well be video games). One could easily question why Anderson is allowed to make movies. They lack memorable plotting, rely on bad CGI, blare loud techno music, and critics pan them. But none of that matters when hordes of fans rush out to see the movie version of their favorite game, which, in turn, proves Anderson financially viable to Hollywood studios.

The movie begins in The Hive, a subterranean lab so vast, we need circling CGI blueprints to see it all. It’s run by the Red Queen, a futuristic supercomputer program in the form of a laser-light ten-year-old British girl with a cold disposition, and the first of many nods to Lewis Carroll literature. The Hive resides under Raccoon City, Umbrella’s very own municipality, fully populated by its employees. In the first scenes, we see a mysterious figure enter a Hive lab and expose the virus for reasons that will become clear (sort of) later. The Red Queen acts to prevent topside exposure, quarantining the entire facility, and condemning everyone in The Hive to death and eventual zombification.

Star Milla Jovovich plays Alice, an amnesiac supersoldier who wakes up in a mansion with fragmented memories. She dolls herself up in a snazzy red dress and finds herself accompanied by a group of Umbrella soldiers on a mission to probe The Hive for survivors. Another amnesiac, Spence (James Purefoy), seems to have had a prior relationship with Alice—according to flickering images in her mind, anyway. Somehow, both are related to Umbrella and The Hive’s contamination, not that we really care once they get inside and start running from zombies.

Inside, the Red Queen seems hell-bent on containing the “T-virus” at any cost, meaning Alice and the others are expendable. By the time they realize this, half of the investigatory team is dead, either by the Red Queen’s defenses or by zombies. One of the men, Matt (Eric Mabius), secretly searches for an anti-virus, which also develops into a priority for the tough female soldier, Rain (Michelle Rodriguez, of Girlfight fame), after a zombie bites her. None of the conspiratorial issues grab us, however. We’re always more concerned about the thrills and the gratuitous zombie gore, which, admittedly, provides some sturdy entertainment value.

These are your typical Night of the Living Dead-type zombies, complete with the bullet-in-the-head Achilles Heel. They come by the hundreds, flooding rooms within a second, making for ample scares. But Resident Evil doesn’t just want to be a high-tech zombie movie; it also delves into science fiction. The team also has to worry about a “Licker,” the result of the “T-virus” inserted directly into living tissue—it’s a big, ugly creature with sharp teeth and claws that looks like something out of Clive Barker’s Hellraiser movies, only conceived with cheap CGI. Even if the protagonists are paper-thin characterizations, we’d still prefer that the zombies or this Licker thing didn’t eat them. The film does a fine job of making us jump until it turns into an actionized conspiracy story that talks about double-crosses and anti-viruses entirely too much.

Jovovich occupies a similar role as in The Fifth Element. She plays an agile female warrior who’s scantily dressed and, at one point, wakes up in a stark room in white strips and responds like a frightened lab rat. She also kicks butt—even zombie-dog butt—in every scene. She fights her way through slews of grabbing and biting undead with her martial arts moves, even with her unreasonable lack of appropriate clothing, while everyone else gets bitten and overrun despite their heavy armor. Anderson’s camera spends a lot of time ogling her, but he eventually married her, so who can complain? Still, she doesn’t imbue her character with personality. I ask you, what are Alice’s defining characteristics, besides amnesia and badassery? Aside from our general hope that Alice doesn’t become some zombie’s meal, there’s no personality here in which to invest ourselves. And so, when Alice begins to shed a tear over Rain’s apparent death, we wonder if we missed some essential moment of character development or dramatic bonding between the two. But you didn’t miss anything; Anderson’s screenplay is inadequate.

George A. Romero, writer and director of the original Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead, invented the contemporary concept of “the zombie”—the slow-moving mode of zombie copied dozens of times in as many films. Romero was originally hired by Sony Pictures in 1999 to make Resident Evil, but Sony fired him because he didn’t comply with their vision for the video game-to-film adaptation. Perhaps too much of Romero’s signature social commentary and too few silly plot developments? Anderson was later hired, and he desperately attempts to make, for unknown reasons, a film infused with Alice in Wonderland references. We have Alice, the Red Queen, and a Looking Glass train tunnel leading from the topside to The Hive. It’s not a clever literary allusion; in fact, Carroll’s book is now a referential cliché, and Anderson’s application is occasionally embarrassing.

One can’t help but daydream about what Romero’s version would have brought to this franchise. And yet, Resident Evil is Paul W. S. Anderson’s best movie next to Event Horizon, which isn’t saying much for his filmography. The film ends on an anticlimax, setting up a sequel and an ongoing franchise. The characters are transparent, and there are too many meaningless subplots that won’t be explained here because who can remember (or care) about their significance to the overall story. Still, if you can manage to shut off your brain, you might allow yourself to get caught up in its claustrophobic action, which has sufficient production value to keep your mind off of the ludicrous storyline.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review