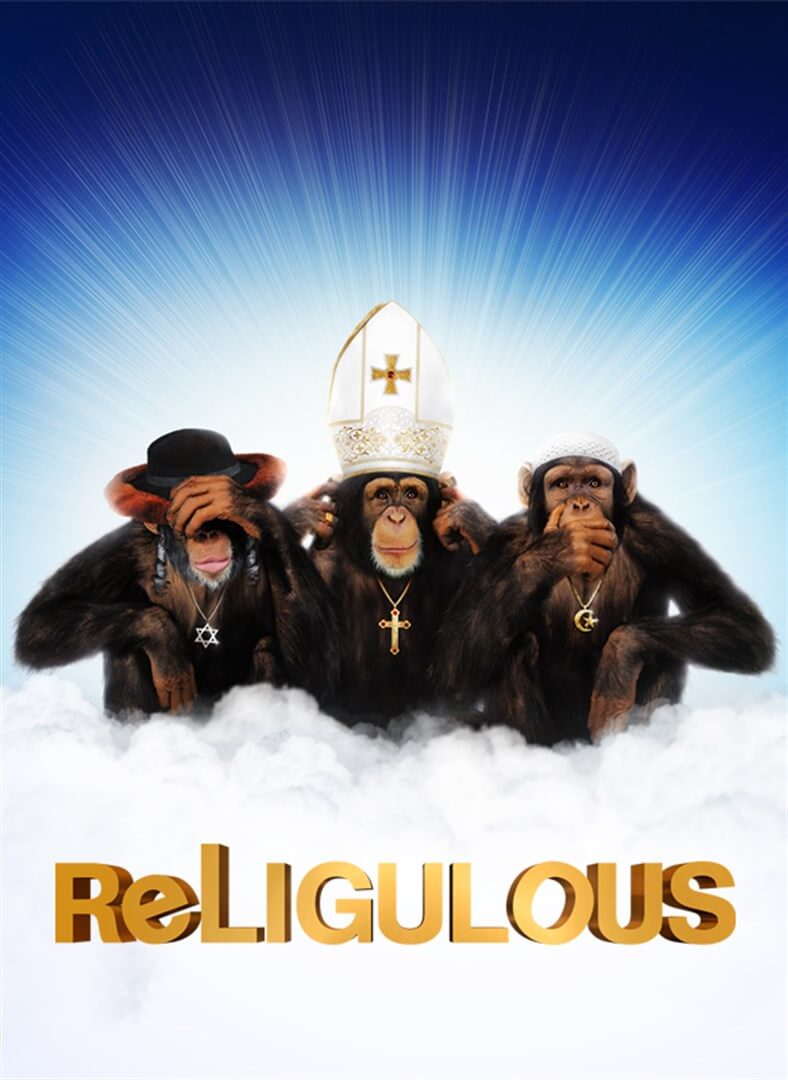

Religulous

By Brian Eggert |

According to Bill Maher, eighty-four percent of Americans probably won’t enjoy Religulous, a film about religious conviction that director Larry Charles describes as a “nonfiction comedy,” because only sixteen percent of citizens are nonbelievers. As we learn from the interviews therein, most believers, even those with a sense of humor, don’t find Maher’s brand of derisive humor funny when it’s at their expense. If you’ve seen Real Time with Bill Maher on HBO or Politically Incorrect, you know he’s smart, stubborn, and doesn’t have much patience for holding a two-way conversation with people he doesn’t agree with. Maher doesn’t agree with any of his interview subjects in the documentary, as he preaches The Book of Doubt. But he doesn’t ridicule the people he speaks with. He respects that some people need religion, that hope is a good thing, and admits to relying on prayer in his lifetime. Instead of blindly accepting religious dogma, however, he questions its logical, historical, and scientific validity, and he explores its various fabricated origins. He’s as polite to his interviewees as one can expect Maher to be, rational at first, and then slowly sarcastic with a touch of Oh, gimmie a break as their talks progress.

After all, should we really believe in talking snakes in the Garden of Eden? Or that Jonah lived in the belly of a whale for three days—oh wait, the Bible calls it a big fish. Is that better? Those stories, two of Maher’s favorites to bring up in the film, are clear allegories for most, like a tall tale with a religious message embedded. But there are others who believe such lore is nothing short of truth. Maher visits a museum in Kentucky dedicated to Creationism, which treats everything—and I mean everything—in the “good book” as historical fact: There’s even an exhibit featuring animatronic human children playing alongside a baby T-Rex, because, after all, the universe started only a few thousand years ago with the dawn of man. (Darwin is spinning in his grave.) Among the different religions, Maher discusses primarily Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Mormonism, and more recent fare like Scientology. Charles recently said he shot hundreds of hours of footage, wherein they no doubt met with Buddhists and Hindus otherwise cut from the film. But Maher’s message is directed at Americans, a country dominated by Christianity, a religion that remains his focus. Reportedly, fourteen hours of assembled material exists from the doc, and it’s been suggested that the footage be chopped into blocks and sold to HBO as a documentary mini-series—a swell idea.

The film’s humor comes from the interviews, and the accompanying commentary added later on in the massive and expert editing process. Maher speaks with a former Satanist, former Mormons, priests, televangelists, and a former homosexual who has since “reformed.” Their comments are shown as somewhat “crazy” through fast referential cuts to absurd religious or educational films, and clever soundtrack choices. Subtitles poke fun at the nonsensical grammar of a U.S. senator, the very same who stated, “You don’t have to pass an IQ Test to get on the Senate.” (Yikes.) And Maher himself is quick, edgy, and hilarious—though he doesn’t resist getting emotionally involved: In one scene, he can’t help but walk away from a rabbi who took part in an Iranian seminar denying the existence of the Holocaust.

An unabashed provocateur, Maher asks questions that make even the most devoted enthusiast pause for a moment. We can see that within their consideration of Maher’s probing, usually common sense-based questioning, during which his subjects realize his logic makes sense. But to admit doubt represents defeat. What follows is a frightening series of denials, the same, says Maher, which contribute to a growing and incessant ignorance among those unforgivably loyal to any religion. Consider the similarities between Christianity and Mediterranean religions from the Bronze Age and earlier, which Maher is sure to point out: Horus of Egypt, Krishna of India, Attis of Phrygia, Mirtha of Persia, and others, all conceived hundreds of years or more before Jesus Christ, share the same traits: each was born on December 25th; each came from a virgin mother; each was martyred; several walked on water; and each was resurrected on the third day. As Maher points out, suddenly Jesus, or those who wrote about him, seem like they were all working from the same template, itself conceived long before Christianity was ever conjured up. When actual historical evidence versus religious belief or faith-based doctrine guides Maher’s argument, it’s difficult not to see his point.

The last moments of Religulous dwell on The End. Maher stands at Megiddo, where, according to Christians, the Second Coming will take place. Is this were Jesus will arrive to judge the living and the dead? If so, it’s none too impressive. It sort of looks like the leftovers of a construction site, with rocks and mounds of sand scattered about the place. Intercut with apocalyptic images of nuclear weapons firing, Maher takes a sobering step away from the humor to advise that we “Grow up or die.”

My feelings on the subject are probably clear, so perhaps I’m inclined toward Maher’s thesis. I’m not going to avoid discussing my personal opinions about Maher’s topic like other film critics, because, frankly, I think that’s missing the whole point. People are fervent about their religions. And while fanatics will always say their wars are about politics, not religion, their politics are products derived from a religious blueprint. Ask yourself why a political candidate’s opinion on abortion, gay marriage, and evolution being taught in schools are top concerns for voters. The “separation of church and state” edicts instilled by our forefathers have gone down the tubes, and as Maher states, how can we move forward to solve issues like pollution, overpopulation, and ongoing war when we can’t even put our religions aside to consider these problems objectively?

Maher asks that we step away from ourselves for a moment to consider our own doubt. Some will be unable to do this and will angrily reject Maher’s message. If while reading this review you felt your pot boiling, avoid the movie. Some may question their beliefs for the first time. Some will embrace the film for punctuating their own feelings of skepticism. Religulous is the kind of product you either love or hate, because its message is so strong, and it’s so subjective. For that sixteen percent of America, however, and those of you willing to admit you have doubts, you won’t find a more thought-provoking documentary this year.

Help Keep Deep Focus Review Independent

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review