Reader's Choice

Red Dragon

By Brian Eggert |

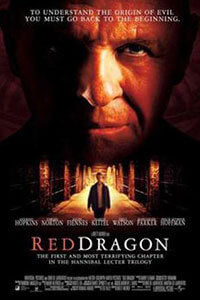

Whether or not you’re familiar with Manhunter, Michael Mann’s 1986 screen version of Thomas Harris’ first book to feature Hannibal Lecter, the 2002 adaptation of the same text, Red Dragon, must be seen. The cast alone warrants your time. Anthony Hopkins reprises his role as Lecter, making his third appearance as the cannibal psychiatrist, following his Oscar-winning bow in The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and the ill-received sequel, Hannibal (2001). But Hopkins feels like an afterthought next to Edward Norton as Will Graham, the FBI profiler who takes down Hannibal in the first scenes. And Ralph Fiennes outperforms them both as Francis Dolarhyde, the disturbed killer with a cleft palate and lingering issues with women, be it the memory of his grandmother or a romantic prospect (Emily Watson). Rounding out the cast is Harvey Keitel as Jack Crawford, the head of the FBI’s Behavioral Science Division (played Scott Glenn originally), and Philip Seymour Hoffman in a small but wonderfully acted role as a sleazeball reporter. Together, they elevate a boilerplate thriller above Mann’s take, as well as its most immediate preceding entry in the Lecter franchise.

A mere 18 months passed between Hannibal’s arrival in theaters and Red Dragon‘s debut. Producers Dino and Martha De Laurentiis couldn’t resist striking when the iron was hot, and Hannibal’s more than $350 million box-office haul meant the Hannibal Lecter brand was indeed scorching. They fast-tracked the only other property available, Harris’ first Lecter book, which was familiar territory for the De Laurentiis Company. De Laurentiis produced and distributed Manhunter, and it bombed, but the time was right for another attempt. (The producer couple would eventually compel Harris to write a prequel, Hannibal Rising, but the less said about that, the better.) Fortunately, the producers convinced Ted Tally, screenwriter of Silence, to adapt the material. They also brought on prestige names like Danny Elfman as composer and Dante Spinotti as the cinematographer. A fourth of the almost $80 million budget went to Hopkins, while the rest went to the high-profile cast. The actual production cost was low, owing to the relatively low-key situations aside from some pyrotechnics in the last act.

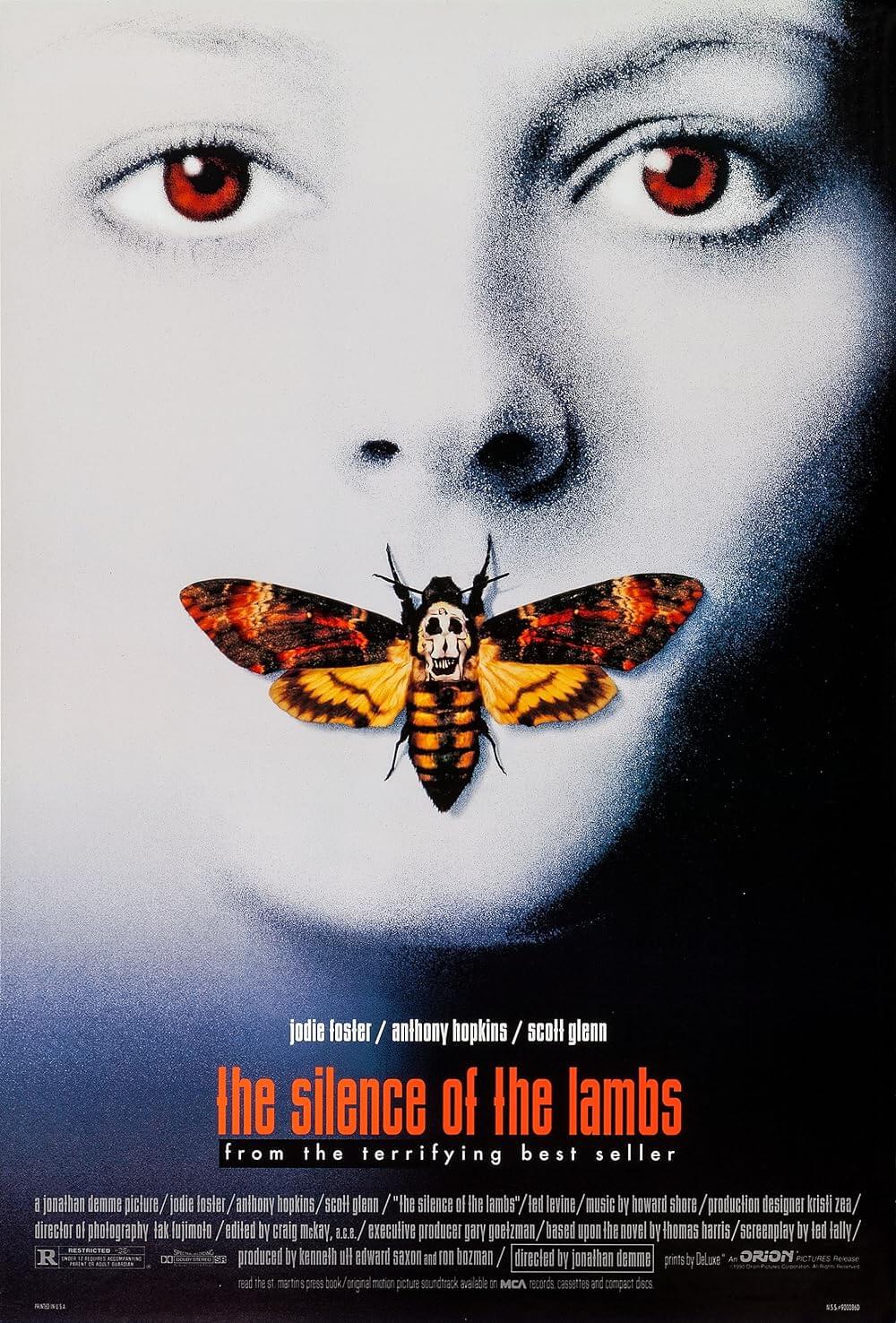

The least impressive credit belongs to director Brett Ratner, who is best known for the Rush Hour series, X-Men: The Last Stand, and other generic fodder (he’s been inactive since 2017 sexual assault and harassment allegations). Ratner has a non-style that presents a sharp contrast to the approach on Manhunter, which was full of Mann’s expressivity in scenes overflowing with ‘80s flair and mood. In Red Dragon, Ratner presents a straightforward thriller aesthetic, complete with a title sequence that follows the Se7en (1995) model—we see patchy glimpses at Dolarhyde’s scrapbook, featuring newspaper clippings and manically written journal entries. The camerawork is mostly invisible and, after Ridley Scott’s overwrought stylization on Hannibal, the back-to-basics approach is refreshing if unmemorable. It’s as though Ratner sought to return to Jonathan Demme’s downplayed treatment of Silence, but he overcorrected and removed the visual treatment of any personality. Even so, it manages to be Ratner’s best film, if only because the cast and script remain strong, and he doesn’t get in the way.

The least impressive credit belongs to director Brett Ratner, who is best known for the Rush Hour series, X-Men: The Last Stand, and other generic fodder (he’s been inactive since 2017 sexual assault and harassment allegations). Ratner has a non-style that presents a sharp contrast to the approach on Manhunter, which was full of Mann’s expressivity in scenes overflowing with ‘80s flair and mood. In Red Dragon, Ratner presents a straightforward thriller aesthetic, complete with a title sequence that follows the Se7en (1995) model—we see patchy glimpses at Dolarhyde’s scrapbook, featuring newspaper clippings and manically written journal entries. The camerawork is mostly invisible and, after Ridley Scott’s overwrought stylization on Hannibal, the back-to-basics approach is refreshing if unmemorable. It’s as though Ratner sought to return to Jonathan Demme’s downplayed treatment of Silence, but he overcorrected and removed the visual treatment of any personality. Even so, it manages to be Ratner’s best film, if only because the cast and script remain strong, and he doesn’t get in the way.

From the outset, Red Dragon is a much more conventional Hollywood serial killer movie than Silence, and it’s almost as though the filmmakers intended a throwback, if only so one could watch the 1991 film and still feel that it was innovating on established archetypes. With that in mind, a standard story demands the customary trappings. For starters, the protagonist, as is usually the case, is a male detective. Norton’s Will Graham has a special knack for understanding serial killers, an “imagination” for detection that he shares with his consultant, Lecter, in the first scenes. When he stumbles upon Lecter’s particular appetite, the two confront and nearly kill each other. Lecter ends up behind plexiglass and under the thumb of some familiar faces—Anthony Heald and Frankie Faison return from Silence as Chilton and Barney, respectively. Graham steps away from the FBI to Marathon, Florida, with his wife (Mary-Louise Parker) and son. Inevitably, Crawford calls him back for one last job to investigate a new string of murders.

Enter Dolarhyde, a warped but not altogether unsympathetic character who grew up under the emotional abuse of his grandmother (never seen, but heard in Dolarhyde’s head with a voice provided by Ellen Burstyn). Dolarhyde has killed two idyllic families so far, and he’ll probably kill another on the next full moon unless Graham can stop him. Graham resorts to Lecter’s help for clues, but Lecter also wants revenge on Graham. Meanwhile, Dolarhyde struggles with the voices in his head, one of whom, the Red Dragon envisioned in William Blake’s painting, is telling him not to seek happiness with a charming blind coworker, Reba (Watson). Watching them together, you fear for Reba even as you hope that her kindness—and horniness, evidenced in a scene where she cops a feel on a sedated Bengal tiger, and then later she repeats the gesture on another powerful creature—might save Dolarhyde. But if that were to happen, there wouldn’t be a movie. Inevitably, things go south for the couple in a tragic and disturbing turn.

Watching Red Dragon in any close proximity to Silence can feel a little odd, given that it’s a prequel, yet Hopkins looks “roomy” (to borrow Lecter’s word) compared to the earlier film. That’s bound to happen after ten years or so. More distracting is how Hopkins’ tendency to bring a certain hamminess to Lecter weakens the character’s scenes with Graham; he can’t resist playing up the role that brought him an Oscar. Norton is more restrained, whereas William Petersen’s Graham felt over-the-top, as though Petersen was still operating on the same extreme required for his rogue cop role in To Live and Die in L.A. (1985). Norton doesn’t show fear in his face-to-face encounters with Lecter in the Baltimore State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, but a scene immediately after their interaction shows that he’s sweated through his shirt, evidently terrified. Small choices such as this elevate the film. Consider Hoffman’s entire performance as Freddy Lounds, a slime-bucket reporter for the National Tattler. When Dolarhyde glues Freddy to a wheelchair, Hoffman’s performance turns in a masterful interplay of terror, shock, and trying to appear on his captor’s side. Unsurprisingly, Hoffman steals his few scenes.

Watching Red Dragon in any close proximity to Silence can feel a little odd, given that it’s a prequel, yet Hopkins looks “roomy” (to borrow Lecter’s word) compared to the earlier film. That’s bound to happen after ten years or so. More distracting is how Hopkins’ tendency to bring a certain hamminess to Lecter weakens the character’s scenes with Graham; he can’t resist playing up the role that brought him an Oscar. Norton is more restrained, whereas William Petersen’s Graham felt over-the-top, as though Petersen was still operating on the same extreme required for his rogue cop role in To Live and Die in L.A. (1985). Norton doesn’t show fear in his face-to-face encounters with Lecter in the Baltimore State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, but a scene immediately after their interaction shows that he’s sweated through his shirt, evidently terrified. Small choices such as this elevate the film. Consider Hoffman’s entire performance as Freddy Lounds, a slime-bucket reporter for the National Tattler. When Dolarhyde glues Freddy to a wheelchair, Hoffman’s performance turns in a masterful interplay of terror, shock, and trying to appear on his captor’s side. Unsurprisingly, Hoffman steals his few scenes.

The standout remains Fiennes, who bulked up for and disappears into the role. Watch the frantic sequence where he runs about his old, dusty manor in the nude, searching for Reba, with the enormous dragon-like tattoo on his back on full display. Tom Noonan, who originated the role in Mann’s film, could give me nightmares without much effort (see The Pledge or Synecdoche, New York). Fiennes does something else altogether, creating a sense of emotional fragility and delicacy in scenes with Reba, but he also bursts into volatile, monstrous violence. It’s strange, but the scariest scene remains when Dolarhyde hopes to silence his inner dragon, and so he visits the museum where Blake’s painting is stored. Somewhere in the killer’s mind, he convinces himself that he must ingest the painting to silence his impulse to murder Reba. So he tears the image apart and shoves chunks into his mouth, an act of possession and self-possession.

The actors do most of the work to make Red Dragon watchable. Without them, the material is handled rather plainly, and it might even be forgettable with another cast. Even Tally’s adaptation bears a striking resemblance to Mann’s script for Manhunter and thus fails to distinguish itself. Both scripts draw equally from Harris’ text, transporting much of the dialogue verbatim and leaving the director and cast to translate. And so, the actors’ choices (and in some cases, sheer screen presence) remain essential to the 2002 film’s superiority. It’s hardly an essential entry in the genre, but next to Hannibal’s style-as-substance approach, it feels familiar and resembles, somewhat superficially, the basic appearance of Silence. If there’s a false note in the whole thing, it comes in the last scene where Chilton and Lecter chit-chat about Clarice Starling’s arrival. Nevermind that Lecter despises Chilton and Barney would have been a better choice for this scene. It’s tacked on just in time to prevent one from praising Red Dragon too much, and instead, remind us that we’re watching a cash cow prequel—albeit a handsomely crafted and impeccably acted one.

(Note: This review was suggested by supporters on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review