Red Dawn

By Brian Eggert |

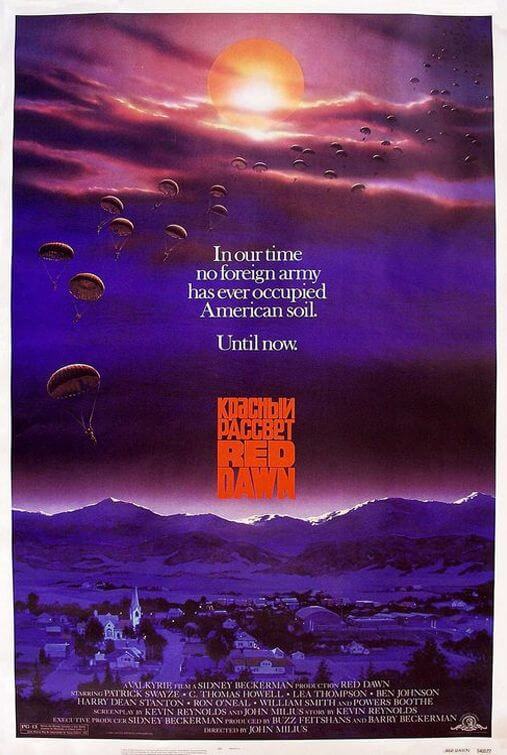

Cold War paranoia and Reagan-era politics set the stage for John Milius’ Red Dawn, the Brat Pack-starrer from 1984 whose aggressive makings dream up a scenario of right-wing extremist and NRA fanfare. Much like the director and co-writer’s primitive yet strangely evocative handling of Robert E. Howard for Conan the Barbarian (1982), Milius takes macho, potentially hammy, certainly nationalist material and imbues it with grave importance. As a result, contemporary audiences may be baffled or altogether bemused by the film’s none-so-subtle political makeup and find the experience unintentionally comical at times. As a piece of film history, however, Red Dawn not only helps define the pervasive sociopolitical climate of mid-’80s but also marks the official debut of the MPAA’s restrictive PG-13 rating after a summer of questionably violent titles. Once the modern viewer transports themselves into the film’s era of origin, it’s not difficult to imagine its impact and therein grasp its staying power as a cult favorite.

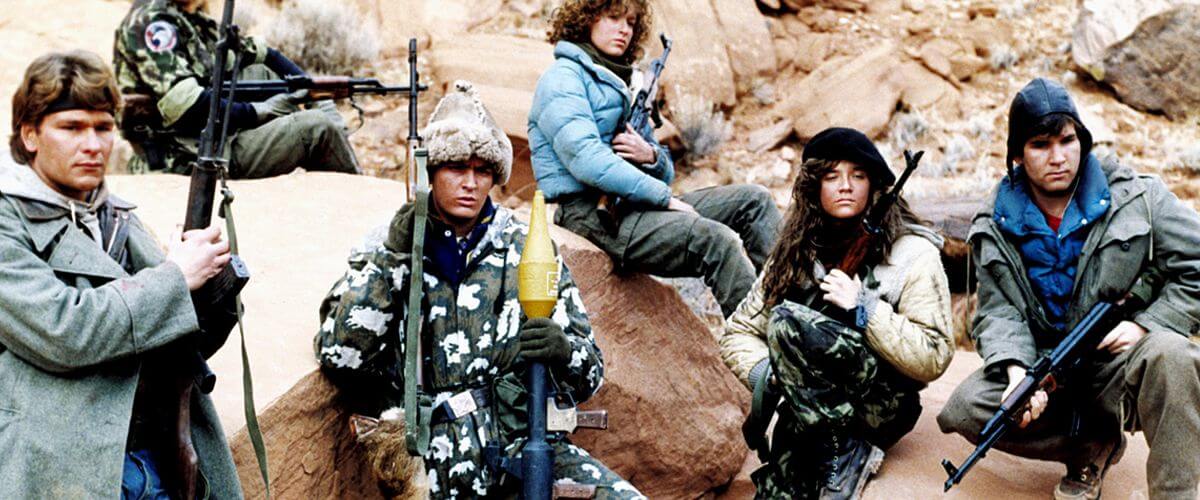

“NATO dissolves and the United States stands alone.” Quick titles like this one hammer out the broad strokes leading to World War III, wherein Cuba, Nicaragua, and The Soviet Union make up the communist Axis of Evil invading the U.S. in the first scenes. Milius wastes no time establishing characters. In the first scenes, paratroopers drop during a high school lecture on the battle strategy of Genghis Khan, and Red machine guns tear down Calumet’s teenage innocents as the communist enemy invades the quaint Colorado town. Tanks and heavy gunners burst onto the scene, while a few youngsters manage to escape with a stash of supplies and hunting weapons into the nearby Arapaho National Forest, the site of the analogous Colorado War. Among the boys who escape are recognizable faces like Patrick Swayze, Charlie Sheen, and C. Thomas Howell, who survive by hunting, a skill taught to them by the former two’s rugged father (Harry Dean Stanton). After Howell’s first deer kill, he drinks its blood and becomes a man, now ready to kill in defense of his land. The boys are later joined by Jennifer Grey and Leah Thompson, who prove their usefulness reaches beyond cleaning up dishes; Grey’s character later becomes a spritely demolitionist.

Before long, the group of youngsters, cut off from the world in the mountains, voyages into town and discovers Calumet has become part of an “Occupied” zone some forty miles away from “Free America”. Their sleepy town is now surrounded by forgotten battlegrounds and patrolling enemy tanks, all led by a former Cuban revolutionary (Ron O’Neal) who grows to despise the occupation and intervention after similar experiences in his own country. In a subtle way, Milius and his co-writer Kevin Reynolds suggest the Cuban ruler even sympathizes with the gang of teens, who eventually become known by their high school football team moniker, the Wolverines, when they begin launching guerilla attacks on Red bad guys. Joining them is a crashed U.S. lieutenant colonel (Powers Boothe), who helps with strategy and hope. The missions carry on for several months, and surprisingly, do not lead to some grand save-the-day goal that marks the end of WWIII. Rather, the youngsters’ numbers dwindle, forcing them into a veritable suicide mission.

Along the way, Milius’ body count piles on more and more during multiple shootouts and violent encounters that aren’t necessarily gory, but the amount of death onscreen earned notices from anti-violence critics. After protests about the level of violence in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and Gremlins, both released earlier in the summer of ’84 with PG ratings, Steven Spielberg convinced the MPAA to inaugurate a PG-13 rating, and Red Dawn was the first to hold this title. But much like First Blood, released two years before, the movie is not designed solely for cheap, bloody thrills. Indeed, however much Red Dawn seems like rich material for a mindless actioner, the film concentrates instead on creating its “What if?” scenario, and feeding on the terrifying notion of a communist state established within U.S. borders, complete with Orwellian “re-education camps” and brainwashing propaganda films blaring in the backdrop. The message seems to be, Damn those complacent Americans who let it happen and do nothing after it’s done! This is contradicted by the evident thrill and pride in the Wolverines for their victories, even as it deplores the circumstances; the filmmakers seem to celebrate the Wolverines more than they lament the disastrous situation that spawned them.

Where the film fails is creating memorable characters, despite the presence of otherwise memorable actors. The performers play roles which, during an early confrontation when the school kids first reach their mountain hideout, differentiate themselves by being either one of the brave ones or one of the scared. No other variation exists, and after a while, they all become good little soldiers. Aside from our familiarity with Swayze and Sheen, and to a lesser extent Howell, the characters seem almost interchangeable, their gradations barely developed. As such, their deaths are met with slight indifference and little emotional involvement. Fortunately, the actors have enough presence and the story enough intrigue to keep us interested. What is most admirable is how Milius shows the kids stumbling through their first kills, and the haphazard way necessity forces them to handle a machine gun with awkward but determined energy. They’re not heroes overnight like some comic book protagonists. The action rarely leads anywhere or deepens these characters, and the Wolverines’ group dynamic never threatens to crumble down upon itself, but the film’s representation of kids-with-guns feels authentic.

Red Dawn is far from an anti-war film and couldn’t be stretched into an anti-violence reading no matter how hard you tried. And yet its purpose is not purely catharsis. It’s not an escapist or fun-loving romp about kids playing soldier (Toy Soldiers comes to mind), nor is it an overwrought explosion of dramatic emotionalism geared up for maximum audience manipulation. The tone is far more thoughtful, if at times confused. Consider the lack of pop culture evident in the film—no corny ‘80s soundtrack; no definite year. One could regard Milius’ treatment as almost mythic, his manner and characters spare, his ending grim and reflective on the historical pattern of occupying powers and the forces that resist them. Most surprising is how much Red Dawn avoids becoming another in a long line of dated ‘80s action movies, as Milius’ complex and alarmingly plausible political setup forces one to wonder what they would do in this situation: fight back or surrender? Milius suggests true Americans fight, and he seems to hold nothing but contempt for anyone else.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review