Red Cliff

By Brian Eggert |

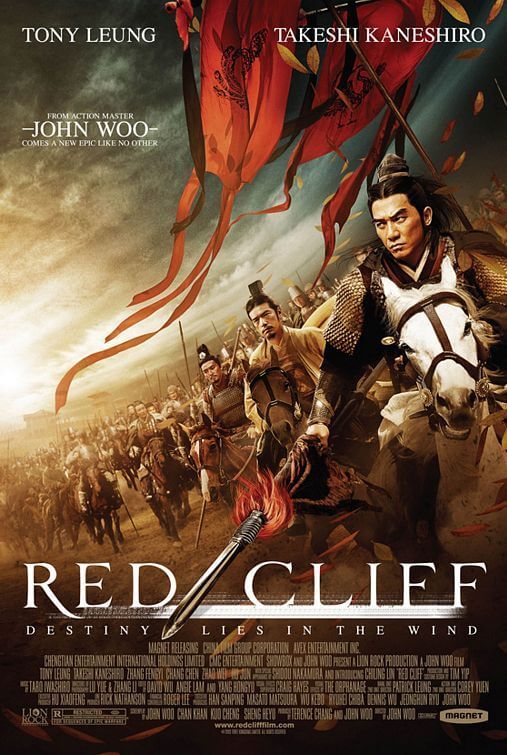

The most expensive motion picture in the history of Chinese cinema, John Woo’s Red Cliff tells the legendary tale of The Battle of Red Cliffs, a massive conflict fought on the Yangtze River around 208-9 AD that marked the end of the 400-year-old Han Dynasty. The Hong Kong action filmmaker returns to his roots for this Mandarin-language blockbuster, also the most successful picture ever at the Chinese box office. And this should’ve been the production where Woo salvaged his reputation, which started with top-notch fare like Hard Boiled and The Killer and was ruined after his long stint in Hollywood releasing garbage like Broken Arrow and Paycheck. But the prestige of the story doesn’t forgive the fact that John Woo lost his edge years ago, and that’s fully evident in every frame of this overlong epic.

Woo, along with a trifecta of screenwriters, revisits what for Eastern audiences is a familiar tale told again and again in various films, histories, comic books, and television series throughout Asia. Chinese literature offers the most enduring of these accounts, a tome by fourteenth-century author Luo Guanzhong called Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Woo’s version comes in the form of two separate films that take up more than four hours, though stateside audiences aren’t privy to the entire diptych experience. Magnolia Films has only imported a heavily cut 148-minute version, so anyone hoping for the as-it-was-meant-to-be-seen screening will probably have to wait until the home video.

The U.S. cut opens with an English-language movie trailer voice introduction, which dumbs down the entire plot enough for those in the audience unfamiliar with the historical setting. A nervous Emperor Xian (Wang Ning) faces his Prime Minister Cao Cao (Zhang Fengyi), who wants to declare war on the southland rebel warlords Liu Bei (You Yong) and Sun Quan (Chang Chen). Cao Cao seeks to reunite the Han Empire by gaining control of the Yangtze and defeating the dissenters, though history proves he succeeded only in causing further division, ushering in the end of the Han Dynasty and a period known as the Three Kingdoms. It all ends in a glorious victory for the warlords over Cao Cao and his forces, which are crushed and allowed to return to their Emperor in shame.

Historically, the heroes of this story have been ambiguous, depending largely on the storyteller. Woo takes sympathy with the warlords, showing Cao Cao as a violent and overconfident warmonger. Liu Bei and Sun Quan’s top strategists, Zhuge Liang (Takeshi Kaneshiro) and Zhou Yu (Tony Leung, who replaced Chow Yun-Fat when he left the production) respectively, prove to be the film’s most interesting characters, as they inspire the union of the warlords’ forces, as well as conceive clever ways to gain a military advantage despite being outnumbered. There’s an interesting sequence where they sneak away with thousands of arrows from Cao Cao’s army, and then them against the enemy in an unprecedented volley on the river, which, despite being visually impressive, is wholly typical in this kind of historical action yarn.

Woo’s action, although the main draw for some audiences, remains the film’s most unsatisfying feature. Epic though the setting and scope may be, this is still a John Woo film, unfortunately. Meaning gunplay and slow-motion bullets are just replaced with swordplay and slow-mo spears flying through the air. Instead of doves emerging from behind his hero, Woo has CGI carrier pigeons lift messages across vast expanses. Battle scenes have large-scale appeal and the costumes, designed by art director Tim Yip, are beautiful. But the presentation is overedited, choppy, and certainly not graceful; there’s also a redundant amount of fade-ins and fade-outs. Long battle scenes and dialogue predominantly about battle strategy are coupled by computer-generated armies from a bird’s eye view, and the same for computer-generated boats during the river scenes. It’s all set to a corny epic score by Japanese composer Taro Iwashiro.

Admittedly, this review is a reaction to the shorter cut, so perhaps the original Chinese cut contains something that this version is missing. Perhaps the editing missteps and slightly exaggerated tone all make sense over four hours. Perhaps the epic movie clichés are lost inside the longer version’s length. But it’s not likely. Red Cliff wasn’t moving, though it had every potential to be; all the right elements were in place, but once again Woo’s direction fails to retain a sense of uniformity. No matter how you cut it, the film’s director hasn’t recovered the talent he had so long ago. After years of being dissatisfied with Woo’s work, this latest disappointment comes as no surprise.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review