Rebel Moon – Part One: A Child of Fire

By Brian Eggert |

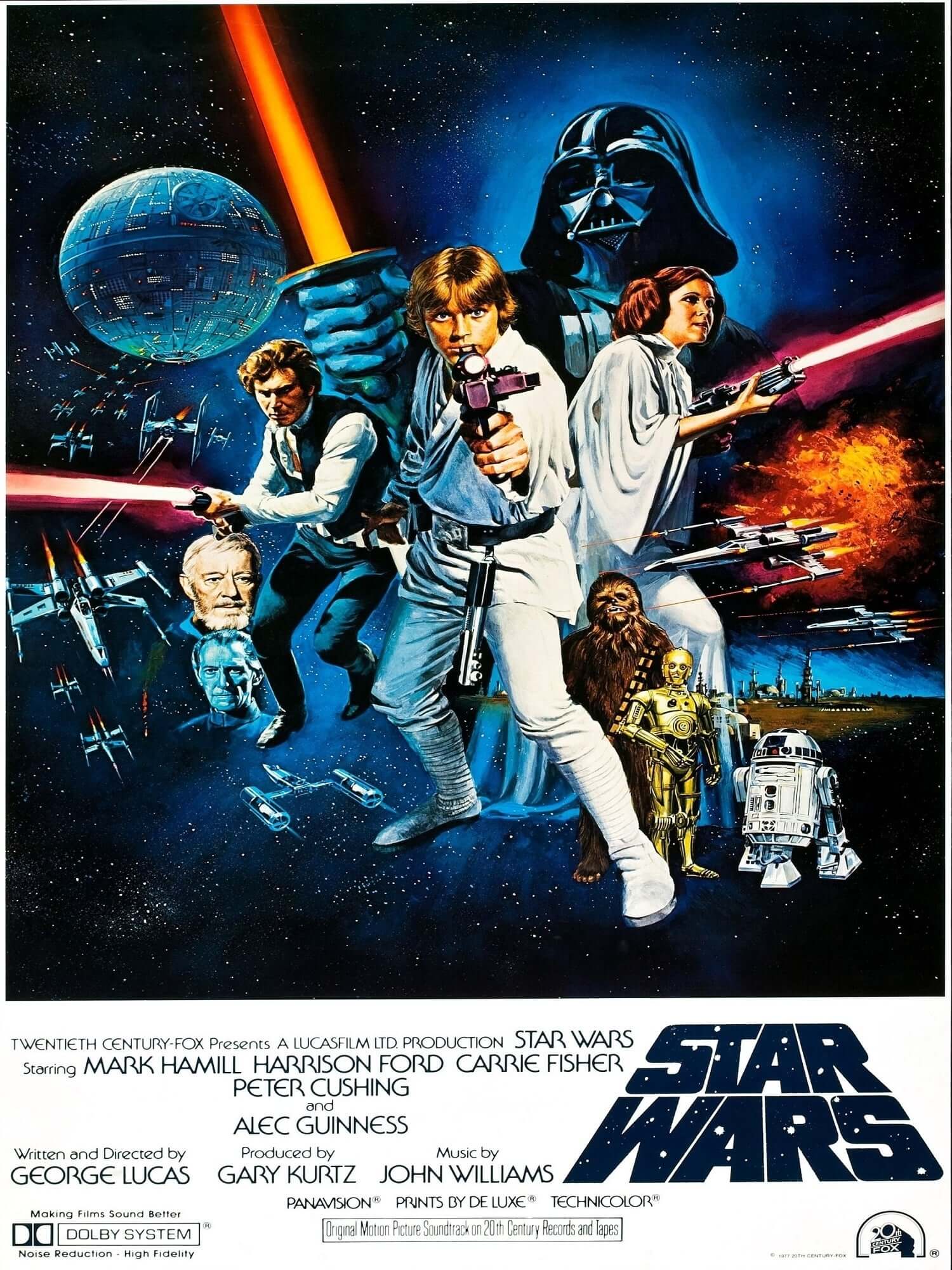

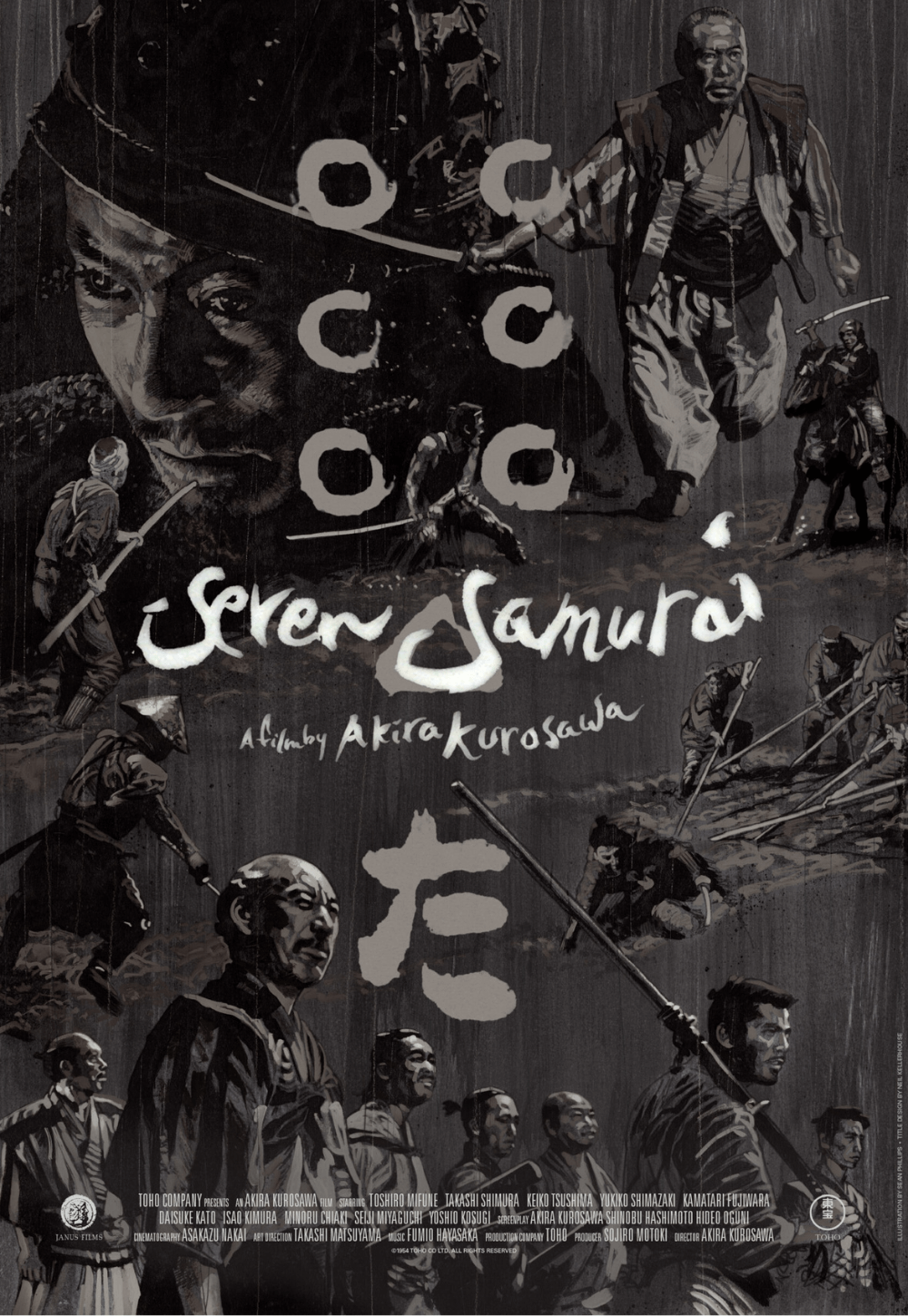

The allusionism is strong with this one. Zack Snyder’s latest visual extravaganza, the loftily titled Netflix production Rebel Moon – Part One: A Child of Fire, draws more than a modicum of influence from Akira Kurosawa’s samurai cinema and George Lucas’ galactic franchise. Of course, Lucas already appropriated bushido honor and aspects of Japanese culture, along with story elements from Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress (1958), to develop the original Star Wars (1977). Snyder’s movie merely draws out the connection further with an amalgam of both filmmakers, offering a hodgepodge of ideas from better movies, repurposed here to lackluster effect. Aside from a few neat aliens and a rousing laser gun battle or two, there’s not much in these familiar proceedings to maintain the viewer’s interest. The movie plays less like an affectionate homage and more like a lifeless and derivative composite, underserviced by Snyder’s interest in cool images over compelling characters. Armed with a talented cast and occasionally impressive visuals, Rebel Moon neither transcends nor pays adequate respect to its influences, making for a flagrant and pedestrian imitation of better material.

The story is an unmistakable copycat of Seven Samurai (1954). That Kurosawa’s all-time classic goes uncredited is troubling, if not grounds for a lawsuit. After all, Italian filmmaker Sergio Leone was sued when he remade Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1962) into the Spaghetti Western A Fistful of Dollars (1964) without permission. And while John Sturges credited Kurosawa’s sprawling and human epic in his remake, The Magnificent Seven (1960), Pixar also borrowed the story structure for A Bug’s Life (1998) without an official acknowledgment. To that end, at least Snyder, who conceived the story and co-wrote the screenplay with Kurt Johnstad and Shay Hatten, has some precedent for not giving Kurosawa’s film an “inspired by” reference here, despite his story following that film’s first half almost beat by beat. Lucas has less of a case against Snyder, who merely borrows the intangible flavor of Star Wars for his world-building details—sci-fi movies have been doing that for years. Still, one wonders if Rebel Moon – Part Two: The Scargiver, set for release in April 2024, will continue with Kurosawa’s story structure. Probably so, given that Part One has so few original ideas.

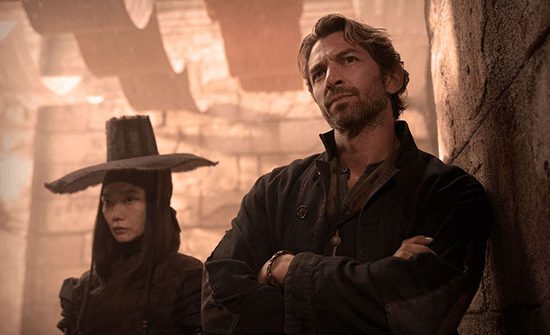

Accented with overblown choral music, the story takes place in a galaxy ruled by an imperialist Motherworld, whose assassinated King (Cary Elwes) was replaced by a brutal ruler, Regent Balisarius (Fra Fee). Determined to quash any dissenters, Balisarius orders Atticus Noble (Ed Skrein) to hunt down rebels. Landing on the habitable moon called Veidt, home to a vaguely Icelandic community of peaceful farmers who have just completed their annual harvest orgy to appease their gods, Noble orders the locals to hand over the bulk of their next reaping in ten weeks to feed his army. Kora (Sofia Boutella), a farmer and former warrior with a mysterious past connected to the Motherworld, refuses to comply and sets out with her village’s harvest manager, Gunnar (Michiel Huisman), to find others who will fight the imperial forces on their behalf. Instead of visiting a local village, as in Seven Samurai, Kora and Gunnar enlist the help of a rogue bounty hunter, Kai (Charlie Hunnam), to help them travel to nearby planets and convince proven fighters to help their cause.

Accented with overblown choral music, the story takes place in a galaxy ruled by an imperialist Motherworld, whose assassinated King (Cary Elwes) was replaced by a brutal ruler, Regent Balisarius (Fra Fee). Determined to quash any dissenters, Balisarius orders Atticus Noble (Ed Skrein) to hunt down rebels. Landing on the habitable moon called Veidt, home to a vaguely Icelandic community of peaceful farmers who have just completed their annual harvest orgy to appease their gods, Noble orders the locals to hand over the bulk of their next reaping in ten weeks to feed his army. Kora (Sofia Boutella), a farmer and former warrior with a mysterious past connected to the Motherworld, refuses to comply and sets out with her village’s harvest manager, Gunnar (Michiel Huisman), to find others who will fight the imperial forces on their behalf. Instead of visiting a local village, as in Seven Samurai, Kora and Gunnar enlist the help of a rogue bounty hunter, Kai (Charlie Hunnam), to help them travel to nearby planets and convince proven fighters to help their cause.

While Kora and Gunnar, profoundly uninteresting characters, search for help, Snyder introduces us to a familiar band of renegades and freedom fighters, each drawn from tropes in Kurosawa’s work: a master of swordplay, Nemesis (Doona Bae); a former general on a gladiatorial world who wants to forget that he surrendered (Djimon Hounsou); Tarak (Staz Nair), a perpetually shirtless warrior who can bond with animals; and Darrian Bloodaxe (Ray Fisher), an insurgent leader who commands the rebellion. Most of these personalities are so thin that the plot mechanics, not the characters and their choices, drive the story. Like Seven Samurai, the movie finds them outnumbered and clashing with their enemies, building to what will probably be a much larger showdown in the sequel. But unlike Kurosawa’s masterpiece, Snyder isn’t interested in giving the farmers much gradation; his treatment is rather like Star Wars in that respect, where good and evil are polarized. Snyder’s grasp of the dimensions in Kurosawa’s film is about as tenuous as the remakes by Sturges or Antoine Fuqua (in 2016).

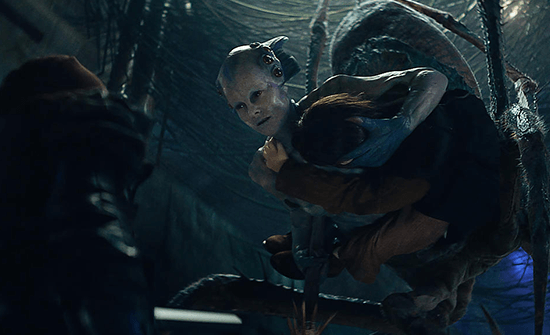

Though the plot follows Kurosawa, most of Rebel Moon’s presentation resembles a Star Wars movie. Snyder originally developed the idea for Lucas’ universe, and his cinematic sampling is unsubtle, from alien-filled cantinas to bad guys imbued with Nazi characteristics. Even the sound effects recall Ben Burtt’s beeps, bloops, and pew-pews from Star Wars. Among Snyder’s innovations—nay, oddities—is the self-aware droid named Jimmy, voiced by Anthony Hopkins, who has a few small scenes early on and for whom Snyder has big things planned, apparently, given its obscurely and unexplained horned appearance in the finale. On the plus side, Jena Malone’s appearance as a spidery humanoid makes for a creepy, inspired sequence, though it leads to Snyder revealing Nemesis’ veritable lightsabers, another dull reference. But the allusions to better movies don’t limit themselves to Kurosawa and Lucas. A sequence straight out of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004) finds a character bowing to a creature that looks suspiciously like a hippogriff.

As ever, the director’s capacity for grandiose-looking cinema remains impressive. Serving as director of photography, Snyder is a compelling visualist, creating iconic images, the ambitions of which often outweigh the capabilities of his reported $160 million-plus budget. The result occasionally has the look and feel of Lucas’ prequel trilogy, with flat backdrops and a deadened digital sheen. Nevertheless, this is unmistakably a Snyder production, complete with his signature use of slow motion to create a sense of awed suspension during action scenes. But even that is a Kurosawa technique. To be sure, Kurosawa employed a similar tactic in Seven Samurai, where he edited slow-motion sequences into otherwise fast-paced action, creating a dramatic juxtaposition of film speeds. That’s been one of Snyder’s tricks since his earliest work, and it’s used here on dramatically falling seeds and a spear-wielding soldier leaping into the air—images that recall Snyder’s own Dawn of the Dead (2004) and 300 (2007).

As ever, the director’s capacity for grandiose-looking cinema remains impressive. Serving as director of photography, Snyder is a compelling visualist, creating iconic images, the ambitions of which often outweigh the capabilities of his reported $160 million-plus budget. The result occasionally has the look and feel of Lucas’ prequel trilogy, with flat backdrops and a deadened digital sheen. Nevertheless, this is unmistakably a Snyder production, complete with his signature use of slow motion to create a sense of awed suspension during action scenes. But even that is a Kurosawa technique. To be sure, Kurosawa employed a similar tactic in Seven Samurai, where he edited slow-motion sequences into otherwise fast-paced action, creating a dramatic juxtaposition of film speeds. That’s been one of Snyder’s tricks since his earliest work, and it’s used here on dramatically falling seeds and a spear-wielding soldier leaping into the air—images that recall Snyder’s own Dawn of the Dead (2004) and 300 (2007).

If this all sounds like I’m dwelling too much on Snyder’s inspirations, know that if Rebel Moon featured better storytelling, perhaps I wouldn’t only see or care about its pilfering. For instance, Lucas wasn’t exactly reinventing the wheel when he made Star Wars; he pieced together aspects of Flash Gordon serials and Japanese samurai cinema to create something familiar but new. But Lucas’ distinct characters, the actors who played them, and the world-building were so inspired that the antecedents hardly registered. He transcended his influences, which is the mark of compelling art. Snyder’s efforts have too few new ideas to distinguish Rebel Moon from its iconic antecedents, making it feel more like a pastiche than an inspired piece of filmmaking that uses its sources as a launchpad. Even as a melange of better material, the PG-13-rated Rebel Moon fails to impress, making the prospect of his promised R-rated extended cut far less intriguing than his alternate take on Justice League (2021). Rather, the upcoming extended version feels like a Netflix gimmick designed to replicate the (faux) hullabaloo around the whole #releasethesnydercut campaign, which, as marketing goes, proves as hollow as the movie it’s attempting to promote.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review