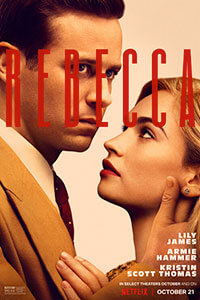

Rebecca

By Brian Eggert |

Adapting a classic novel into a visual format for the umpteenth time requires a new perspective on the source material. Otherwise, a film risks being overshadowed by earlier adaptations. That’s the unfortunate fate of Ben Wheatley’s Rebecca, based on the 1938 novel by Daphne du Maurier. A hugely popular book that has never been out of circulation, its adaptations have appeared on stage, Masterpiece Theater-style television, and of course, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 film, which won the Oscar for Best Picture. As a cinephile with a penchant for classic Hollywood, seeing Wheatley try to maneuver in Hitchcock’s shadow is painful. He’s a talented director, to be sure, but his version doesn’t bring anything that considers the book in a new light or makes it urgent viewing for today’s audiences, except for the fact of its newness. Unnecessary and without a distinct enough voice to justify its existence, Wheatley’s version, housed on Netflix, not only fails to live up to Hitchcock’s classic, but it eschews much of the Gothic mood and atmosphere that distinguished the original book and film.

While it’s perhaps unfair to consider the new version through the lens of Hitchcock’s adaptation, Wheatley forces the comparison by replicating flourishes from the 1940 film. For instance, both open with the line, “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” Sure, it’s the first sentence of du Maurier’s book, but Wheatley repeats Hitchcock’s choice to use the protagonist’s first-person narration early on and then gradually forget about the voiceover device as the film unfolds. Wheatley also takes visual cues from Hitchcock, such as the chiaroscuro sequence where the dreaded Mrs. Davers, played by Kristin Scott Thomas here, Judith Anderson in the original, holds an oil lamp low, causing a severe light to shine upwards to accentuate her icy features. Both, too, introduce the sprawling Manderley with a shot that follows the long driveway to the looming Cornwall estate (actually Cranborne Manor in Dorset for the exteriors). The similarities suggest that Wheatley sought to adapt the book for a new generation and remake Hitchcock’s film. That in itself is not a crime, unless you don’t have anything to add to the conversation.

For the uninitiated, the story follows an inexperienced and fragile protagonist (Lily James) who works as an assistant to a pompous and intolerable lady, Mrs. Van Hopper (Ann Dowd). While tending to Mrs. Van Hopper in Monte Carlo, she meets an alluring British nobleman, Maxim de Winter (Armie Hammer), a recent widower. They quickly fall for one another—as characters in cinema often do, in a montage—as Maxim sweeps James’ character away with his sophisticated class and genuine charm. Never mind his mood swings at the mere mention of his late wife, Rebecca, seemingly because he remains heartbroken. After a swift marriage and honeymoon, James becomes the second Mrs. de Winter, who returns to Maxim’s home in Manderley to find herself gripped by the ghostlike memory of Rebecca, who was “irresistible” and incomparable to “us mere mortals,” says Maxim’s sister (Keeley Hawes). James’ character is made to feel like an outsider living in Rebecca’s wake—not only because Manderley still contains all of Rebecca’s things, but because the head housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers (Thomas), arranges several humiliating episodes to make her feel inadequate next to Rebecca.

The screenplay, credited to Jane Goldman, Joe Shrapnel, and Anna Waterhouse, hits most of the same story beats as Hitchcock’s film. The giveaway that the new take borrows from the earlier production is how both films handle the twist about Rebecca’s mysterious death. Du Maurier’s book reveals that Maxim, driven to the brink, shot his wife in a heated moment (the author had a way of making her readers empathize with characters who frequently do horrible things). Working under the Production Code, which would have never allowed Maxim to get away with murder, nor the couple to live happily ever after, Hitchcock altered this detail to something less salacious. Wheatley’s film makes that same alteration to the source material, despite the Code and its moral mandates being long gone. In that plot point alone, Wheatley avoids confronting his audience or delivering something unconventional with his adaptation.

The screenplay, credited to Jane Goldman, Joe Shrapnel, and Anna Waterhouse, hits most of the same story beats as Hitchcock’s film. The giveaway that the new take borrows from the earlier production is how both films handle the twist about Rebecca’s mysterious death. Du Maurier’s book reveals that Maxim, driven to the brink, shot his wife in a heated moment (the author had a way of making her readers empathize with characters who frequently do horrible things). Working under the Production Code, which would have never allowed Maxim to get away with murder, nor the couple to live happily ever after, Hitchcock altered this detail to something less salacious. Wheatley’s film makes that same alteration to the source material, despite the Code and its moral mandates being long gone. In that plot point alone, Wheatley avoids confronting his audience or delivering something unconventional with his adaptation.

Rather than drench his production in Gothic shadows—a style employed by Hitchcock, inspired by German expressionists—Wheatley, production designer Sarah Greenwood, and d.p. Laurie Rose consciously avoid them. It’s a counterintuitive choice for a story rooted in uncertainty and pointed ambiguity. But if there’s a major departure from Hitchcock in this Rebecca, it’s how the production amplifies the decorative luster of Manderley (actually Hatfield House in Hertfordshire for the interiors), infusing the manor’s spaces with decadent flowers, woodwork, and artwork. The color, too, seems to be heightened for this upstairs-downstairs affair, giving the production the suspicious look of an episode of Downton Abbey. Doubtless, the sumptuous, well-lit details are meant to convey our protagonist’s sudden and jarring immersion into a busy home, making the viewer share the second Mrs. de Winter’s feeling of being overwhelmed by her new surroundings. Still, along with the sometimes patchy editing by Jonathan Amos, the visually overstimulated result feels like a miscalculation on Wheatley’s part.

At the center of Rebecca are a couple of good performances and a couple of forgettable ones. Thomas has the meatiest role as Mrs. Danvers, though she plays it with less subtlety than Anderson, more obviously enjoying her torture of the second Mrs. de Winter (“No one wants you here,” she says with a sociopathic smile). Sam Riley is also deliciously scheming as Jack Favell, Rebecca’s former lover. But the leads, Hammer and James, fade into the scenery, imbuing their characters with none of the passion and rawness found in the original’s Laurence Olivier and Joan Fontaine. Throughout, it feels as though most of the cast is playing pretend. One might blame the elaborate production or Wheatley’s amplified style for their disappearance into the scenery—which occasionally descends into a CGI flourish, such as a lousy looking nightmare sequence where animated plants pull our protagonist into the floor or the cartoony fire at Manderley. But the entire production, however handsome, never grabbed me. Much like the second Mrs. De Winter in the story, the new Rebecca is mostly uninteresting compared to Hitchcock’s original.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review