Ready Player One

By Brian Eggert |

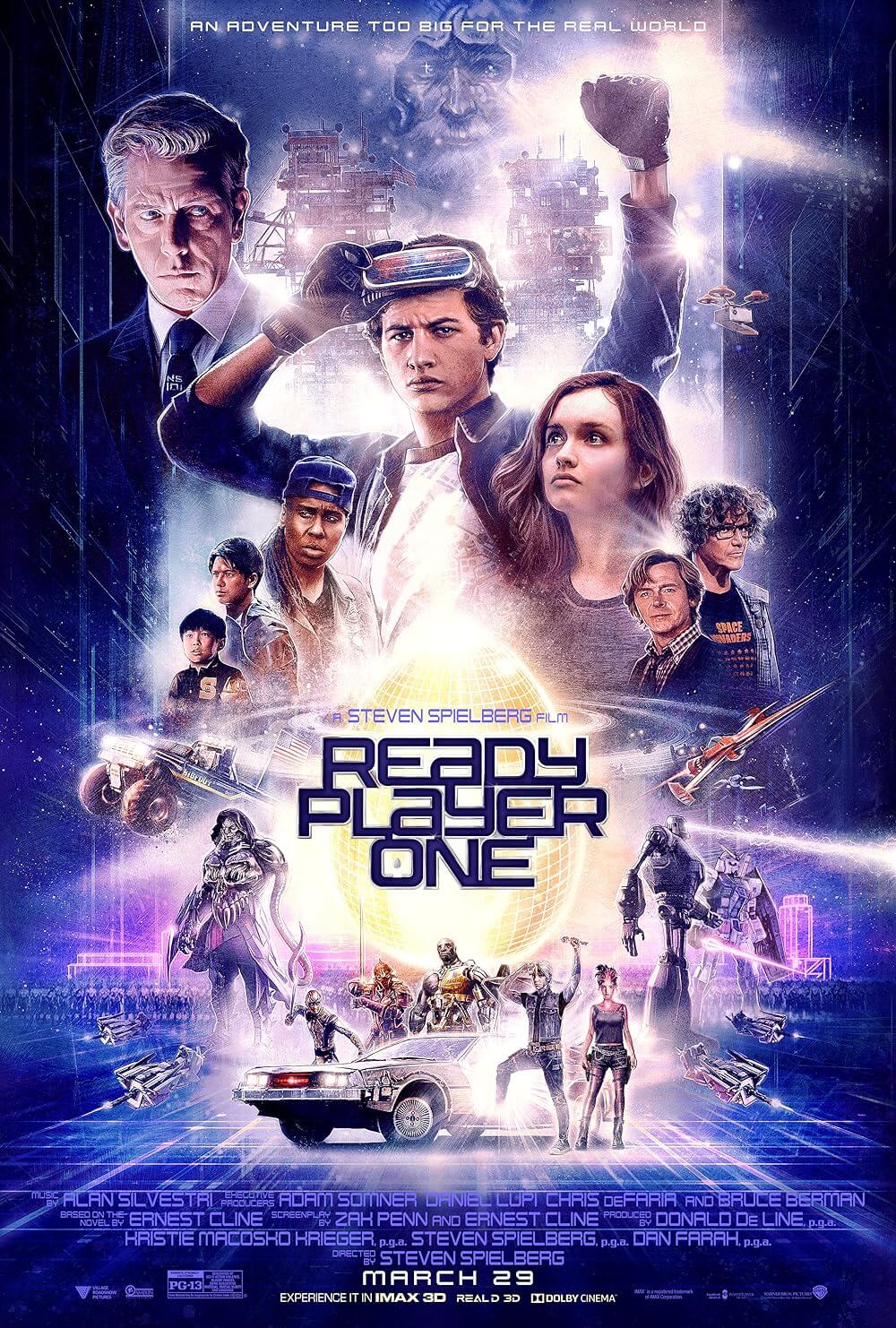

With Ready Player One, you can feel director Steven Spielberg pushing to reclaim his status as Hollywood’s crowned head of spectacle as he pours his considerable talent into another memorable science-fiction fantasy. An imaginative sensory assault, the picture finds Spielberg doing what he does best, which is borrowing here and there to pioneer new ideas and formal bravado. From Jaws (1975) to Jurassic Park (1993), Spielberg’s grandiose, hybridized style has fused familiar concepts into entertainments both iconic and innovative. But his critics claim that he’s lost his former glory in recent years with disappointments like Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2007). Detractors be damned. At the age of 71, the director’s willingness to continue challenging himself has resulted in his most purely entertaining work in more than a decade—a film of youthful energy and vision. His adaptation of Ernest Cline’s 2011 novel, a text inspired by Spielbergian tropes of the 1980s (among countless other influences), settles the director back into familiar trappings: robots, laser guns, and the dangers of advanced technology, which inspired everything from Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) to Minority Report (2002) to War of the Worlds (2005). Spielberg once again makes his mark on the sci-fi genre and leaves the viewer of Ready Player One in a state of exhaustion and exhilaration.

Mixing ingredients from TRON by way of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, Cline’s novel unabashedly embraces ’80s nostalgia like few other books or films have. Saturated with nerdy references to arcade games, Japanese television, and movie culture, the relentless page-turner also contained heartfelt characters and a touch of romance. Yet Cline’s enthusiasm for yesteryear’s pop-culture amounts to more than a compendium of strung together references. The author contains them within an intricate and believable science-fiction world, derived from cyberpunk virtual realities and modern role-playing games (RPGs). His story, set in 2045, finds overpopulation driving the cramped younger generations into the Oasis, an RPG virtual reality universe that blends the artificial and real in often troubling ways. It’s distinct from Hollywood’s recent future worlds, even last year’s similarly themed Blade Runner 2049, where reality and artificiality presented two marked perspectives. Issues of class, economic well-being, and survival spill into the Oasis from the real world, and vice versa, underscoring a subtle and germane commentary on our overinvestment in online cultures.

Cline co-wrote the screenplay with Zak Penn (another gaming enthusiast, if his 2014 doc Atari: Game Over is any indication), and they deviate from the source material enough so readers will notice. The spirit and structure of the novel remain, but the film omits the text’s long sequences of video game playing or listmaking—sequences that, if in a film, would not be, well, cinematic. The basic story elements remain intact, with perhaps more concentration on the real-world stakes than the page. Wade Watts (Tye Sheridan, perfectly cast) lives in the “stacks” of Columbus, Ohio, where the teeming population has just started to build upwards. With the physical world cramped, people spend their time in the Oasis, a virtual universe of unlimited possibilities. But not unlike World of Warcraft or other contemporary RPGs, people spend real money on improving their Oasis avatar. When users rack up too many expenses, the evil corporation Innovative Online Industries (IOI) purchases their debt and turns them into a wage slave—a prisoner in IOI’s ever-growing debtor army.

The Oasis designer, the late James Halliday (Mark Rylance, also perfectly cast), never intended his creation to rule society, nor become the object of socioeconomic peril. Rather, just before his death, five years earlier, as Wade’s narration explains, Halliday announced a contest: Whoever unlocks his Easter Egg (the term for something hidden inside a video game by its designer), located somewhere in the vast cyberscape, will earn his half-trillion-dollar legacy and control over the Oasis, the digitized world’s most valuable resource. Attaining said bounty has become the sole aim of IOI and its corporate stooge, Nolan Sorrento (Ben Mendelsohn), who’s hired Halliday experts and gamers to locate the three hidden keys to unlock Halliday’s treasure. Competing against Sorrento’s machinations are egg hunters (or “gunters”) like Wade, enthusiasts determined to keep their virtual home-away-from-home free from the moneygrubbing hands of IOI.

Spielberg alternates between a grimy, grayed-out reality and the intentionally cartoony CGI wonderland of the Oasis, where Wade resembles a Final Fantasy character. Inside, he goes by his avatar’s name, Parzival, and he teams up with a group of other gunters to outplay IOI. His best friend, Aech (Lena Waithe), looks like a cybernetic orc, while Art3mis (Olivia Cooke) remains his badass love interest—a rebel both inside and outside of the Oasis. Their virtual selves have been motion-captured and rendered via convincing computer animation, with just enough animated style to make them look like next-gen characters (details gamers will appreciate). Their gameplay comes in wondrous displays of color and slick graphics, but Spielberg’s editors Sarah Broshar and Michael Kahn keep the audiences tethered to the real-world at all times. Some of Cline and Penn’s most effective changes from the book involve IOI’s willingness to resort to physical threats, not just virtual ones; and the advanced suits worn by Oasis players offer lifelike sensations, including pain.

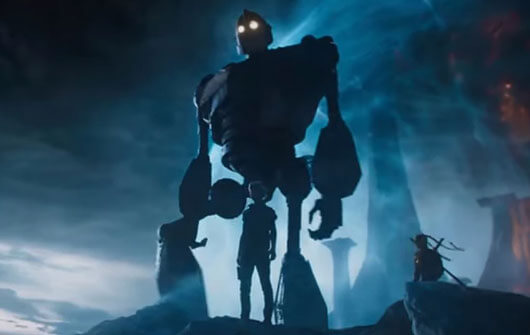

Spielberg’s thrill-ride filmmaking comes to the fore in breathless sequences, dizzyingly orchestrated with surprising visual clarity despite the abundance of onscreen stimuli. When the film debuted at SXSW, Spielberg introduced the screening and described the production as an “anxiety attack” given the amount of CGI animation involved. After all, Spielberg could storyboard every scene and shot alongside cinematographer Janusz Kaminski, but the animators at Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), along with a dozen other FX houses, would assemble the Oasis. Granted, Spielberg trusted animators with The Adventures of Tintin (2011), his outstanding and underrated animation debut; but he also trusted them for perhaps his most underwhelming film in three decades, The BFG (2016). And sure enough, ILM loads every moment in the Oasis with winks and brief appearances by pop-culture’s most memorable icons. There’s an amusing anecdote Spielberg has told about supervising ILM’s animation and realizing, only after several passes, that they injected one of the monsters from the Spielberg-produced Gremlins (1984).

Some may complain that Ready Player One is a film in which the viewer is meant to derive too much joy from spotting a nonstop onslaught of Easter Eggs—everything from RoboCop to Ninja Turtles, from Buckaroo Bonzai to the Beastmaster, from Arkham’s Harley Quinn to Hello Kitty. To be sure, there’s a certain charm to watching (and rewatching) these scenes to spot every pop-culture bonus. But as Spielberg told the SXSW audience, “The side windows are for cultural references. The windshield is for the story.” The trappings of the Oasis make for a fun backdrop, nothing more. The human story about Wade, Art3mis, and their friends keeping the dastardly Sorrento away from Halliday’s prize remains central, in particular because the writers have reformatted the journey to reveal some emotional detail about Halliday himself. Video flashbacks of Halliday working alongside his former partner Ogden Morrow (Simon Pegg), and the two clashing over the future of the Oasis, reveal the virtual world to be a labor of love and regret, portrayed by Ryland in his shy and awkward characterization. Wade’s admiration of Halliday is reflected in his sense of his own untapped potential, and his pure belief that he too understands the full potential of the Oasis.

To those who balk at the sheer volume of references, note that Spielberg and other New Hollywood filmmakers have always been about paying homage to earlier films. Most moviegoers just maintain too narrow a perspective on film history to realize it. Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) wouldn’t exist without matinee serials, for instance; Jurassic Park wouldn’t exist without King Kong (1933) and The Lost World (1927). Moreover, there’s a loving quality to his self-reflexivity toward his own legacy or, say, the appearance of a Zemeckis Cube—a Rubik’s Cube that, when solved, turns back time by 60 seconds—a nod to his collaborator Robert Zemeckis of Back to the Future fame. Of course, on a purely visual level, Spielberg’s direction is assured and fluid. His images move through both the real world and the Oasis with an equal degree of urgency, and to be sure, this is a faster-paced film than his others. A longtime gamer himself, Spielberg captures the amped-up tempo of today’s video games, but he never sacrifices clarity for speed.

When someone with Spielberg’s unquestionable talent sets out to redefine the Hollywood spectacle, audiences should be prepared for something special, even if its exceptional qualities are tied up in entertainment value. The high degree of fun Spielberg delivers is indeed special. Ready Player One feels like the work of a much younger filmmaker, which is to say, Spielberg reclaims his former mastery of the blockbuster. (Then again, this critic would argue he never lost it, while his harsher critics probably won’t give the film much of a chance anyway.) He understands this world and seems to be having a blast exploring it. The fun he’s having proves infectious, whether he’s exploring the hallways of the Overlook Hotel in an inspired extended sequence, or he’s watching Wade maneuver down the stacks. The film’s ambitions aren’t high-minded, but Ready Player One is lively pleasure that captures the appeal of Cline’s charming book. Just because you should give yourself over to this eardrum-rattling, eye-popping presentation on the largest multiplex screen you can find, it doesn’t mean the experience will be emotionally vacuous and fail to provoke thought. Just as Cline’s novel demonstrates, an amalgam of familiar references and tropes can be combined into an engrossing fairy tale on its own merits.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review