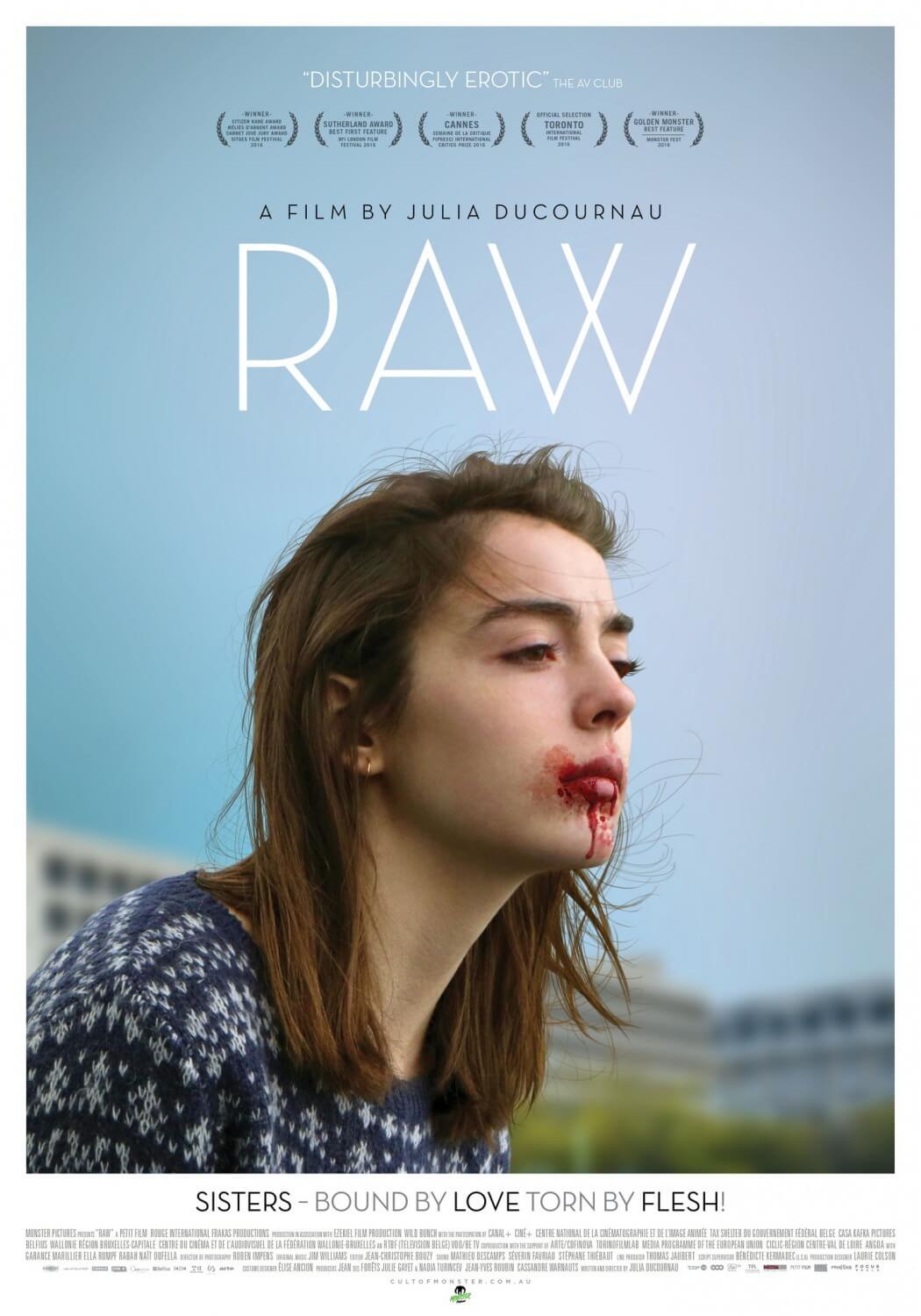

Raw

By Brian Eggert |

The first-year veterinary students gather as ordered. The older students, who demand to be called “elders” or “Great Ones,” throw the newbies’ mattresses out the window, force them to crawl on all fours, and dress them in lab coats for a macabre tradition: they douse the freshmen in a shower of blood from above before lining them up for the climax of this initiation—each new student must eat a raw rabbit kidney, followed by a shot of liquor. In Raw, the debut feature film from French writer-director Julia Ducournau, these cruel rituals spark an awakening of Cronenberian proportions. The film, set against the backdrop of university hazing, explores a young straight-A overachiever discovering new desires and pleasures of the flesh. Ducournau uses one taboo subject, cannibalism, to mine the sometimes-taboo subject (at least in certain conservative circles) of female sexuality on film. Creating a rich metaphor for coming of age and sexual awakening, Ducournau achieves a brilliantly feminist network of intellectual and bodily symbols. Full of visceral horror and a thoughtful meditation on the various hungers of youth, Raw is a blazingly original and confidently crafted debut.

Justine (Garance Marillier), a sweetly naive 16-year-old prodigy, follows her family’s strident traditions as both a vegetarian and a veterinarian. We see as much when her mother responds to a rogue meatball in Justine’s mashed potatoes like a chunk of poison. Justine’s distaste for animal flesh has been thoroughly entrenched, so eating a rabbit kidney marks a first. Her rebellious older sister, Alexia (Ella Rum), urges her to comply with the ritual out of tough love. Pressured, Justine concedes and nearly vomits afterward. At university, their sisterhood becomes combative—Alexia wants Justine to conform to the school’s disturbing blend of booze, sex, parties, and ghastly games, and she grows frustrated with her sister’s inexperience. Justine adapts quickly and, soon enough, they will bond in their shared tastes, even if there remains a rivalry over the attention of Justine’s gay roommate, Adrien (Rabah Nait Oufella).

The tiny morsel of meat leads to an allergic reaction in Justine, but it also awakens a new hunger. It starts with a nasty rash and Justine’s frantic itching, followed by a newfound curiosity about the taste of meat. Embarrassed by the desire that goes against her upbringing, Justine and Adrien leave campus for some gas station shawarma, which she munches down with ravenous intensity. But her carnivorous taste quickly enters yucky territory when she bites into a midnight snack of raw chicken breast with orgasmic delight. At the same time, the hazing continues with late-night bacchanalia and dorm room games. One such game finds Justine doused in blue paint by the older students; they lock her in a room with a boy painted yellow and tell them, “Don’t come out until you’re green.” Her insatiable yearning for flesh leads to a nibble that removes a chunk from the boy’s lip. Later, when she showers off the paint, she picks the bit of lip from her teeth and decides to consume it.

Like most of us during this formative period, Justine doesn’t understand what’s happening to her body and follows her impulses. It’s not until a freak accident during a botched Brazillian wax job that Justine gets her first real taste of human flesh. She jolts when Alexia tries to free a troublesome strip of wax with scissors and inadvertently cuts off her sister’s finger. Alexia faints, leaving Justine to taste a few drips from the severed digit before chowing down like it’s a chicken wing. When Alexia wakes, her eyes fill with tears at the sight, but not for the reason you might think—Alexia, too, has cannibalistic desires and, perhaps, recognizes the aberrant turn Justine’s life will now take. In the role of a sibling-mentor, Alexia teaches her younger sister the ropes: Together, they wait out of sight on a country road until a car approaches. Alexia leaps out, causing a vehicle to swerve and the passengers to die. It’s fresh meat. Sisters often deepen their bond over their common ground, but rarely if ever while licking someone’s head wound.

Like most of us during this formative period, Justine doesn’t understand what’s happening to her body and follows her impulses. It’s not until a freak accident during a botched Brazillian wax job that Justine gets her first real taste of human flesh. She jolts when Alexia tries to free a troublesome strip of wax with scissors and inadvertently cuts off her sister’s finger. Alexia faints, leaving Justine to taste a few drips from the severed digit before chowing down like it’s a chicken wing. When Alexia wakes, her eyes fill with tears at the sight, but not for the reason you might think—Alexia, too, has cannibalistic desires and, perhaps, recognizes the aberrant turn Justine’s life will now take. In the role of a sibling-mentor, Alexia teaches her younger sister the ropes: Together, they wait out of sight on a country road until a car approaches. Alexia leaps out, causing a vehicle to swerve and the passengers to die. It’s fresh meat. Sisters often deepen their bond over their common ground, but rarely if ever while licking someone’s head wound.

Ducournau’s portrait of Justine’s maturation links sexuality with cannibalism in smart but horrific ways. For one, Justine’s initial empathy for animals—she argues that a raped monkey experiences the same trauma as a raped woman, much to her peers’ rejection of that hypothesis—gives way to her knack for slicing into a dog cadaver with detached ease. Her blossoming into a woman comes with an aggressive first-time sexual encounter with Adrien, who contends with Justine’s attempts to bite him and looks disturbed when she climaxes while sinking her teeth into her wrist. It’s a confusing time between her bloodlust, bursting carnality, hazed humiliations, and excessive partying. Her newly deepened bond with her sister mutates as well. Their competition and codependence warp into resentment, leading to some public displays of rapaciousness that threaten to destabilize her already uneven campus reputation. A video involving Justine trying to bite a corpse in the morgue, the cannibal equivalent of a college sex video, spreads around the student body to traumatizing effect, turning her into the university’s resident sicko.

Ducournau’s vision is clear and unwavering. Every visual, aural, and thematic flourish works in unison. Ruben Impens’ eerily cool cinematography creates powerful images marked by the reality of flesh—darkly and almost clinically composed, albeit with a clarity that refuses to shy away from the body’s meatbag quality. Delirious subterranean party scenes twist European pop music into seedy displays of overstimulated bodies dancing in hues of pink and blue light. The director’s choice of death rap is both apt and provocative during a scene where Justine dances in the mirror, kissing and licking her reflection with the image in a mirror-eye-view reflection—one of several times she seems to look into the camera and ask, “What do you think of me now?” Elsewhere, Jim Williams’ non-diegetic score uses organs and synthesizers for a decidedly modern take on old-fashion horror motifs, as though Raw served up a contemporary version of Giallo scores by The Goblins—the lighting of the school’s parties, too, recalls Dario Argento’s use of color in Suspiria (1977). Filmed on location in Belgium at La Faculté de Médecine Vétérinaire, Ducournau captures the grounds’ Brutalist architecture that recalls the vaguely futuristic structures in Cronenberg’s early films such as Shivers (1975) and Rabid (1977). And while Ducournau draws from many influences, she resists outright homage, which leaves Raw to feel free of pastiche.

Ducournau’s greatest asset is Marillier, who was just 18 when the film was made. She gives a fearless and bold performance, conveying a character who must transition from a sheltered girl into a grown woman by the final shots. Ducournau immerses the viewer in Justine’s subjectivity so that her moments of cannibalism remain more potent for their character development than their sheer horror. It’s a conceit that challenges the viewer to sympathize with the protagonist on her dark journey of self-discovery. We experience her frightening new impulses through dreams and hallucinations—among them a sequence under the covers, where she’s prodded by her hunger. No matter how grim things become, Ducournau manages to keep us on Justine’s side, in part because Marillier’s presence remains human—even in monstrous moments where she consumes blood and looks into the camera defiantly. It’s the kind of performance that deserves to be called fearless. Marillier has worked with Ducournau since the age of 12. She first appeared in the director’s 2011 short Junior, followed by Ducournau’s first feature-length project, Mange (2012), co-written and directed alongside Virgile Bramly for French television.

Ducournau’s greatest asset is Marillier, who was just 18 when the film was made. She gives a fearless and bold performance, conveying a character who must transition from a sheltered girl into a grown woman by the final shots. Ducournau immerses the viewer in Justine’s subjectivity so that her moments of cannibalism remain more potent for their character development than their sheer horror. It’s a conceit that challenges the viewer to sympathize with the protagonist on her dark journey of self-discovery. We experience her frightening new impulses through dreams and hallucinations—among them a sequence under the covers, where she’s prodded by her hunger. No matter how grim things become, Ducournau manages to keep us on Justine’s side, in part because Marillier’s presence remains human—even in monstrous moments where she consumes blood and looks into the camera defiantly. It’s the kind of performance that deserves to be called fearless. Marillier has worked with Ducournau since the age of 12. She first appeared in the director’s 2011 short Junior, followed by Ducournau’s first feature-length project, Mange (2012), co-written and directed alongside Virgile Bramly for French television.

Raw might be considered a late entry in the gristly subcategory of New French Extremity, where French filmmakers have experimented with bloody and transgressive imagery loaded with poetic meaning. A label coined by James Quandt in Artforum, New French Extremity reached its height in the early 2000s with Alexandre Aja’s High Tension (2003), Xavier Gens’ Frontier(s) (2007), and Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs (2008). However, arthouse filmmakers have also employed the style for their own provocative purposes, as evidenced in Gaspar Noé’s Irréversible (2002) and even Claire Denis’ Trouble Every Day (2001). Several films in this minor movement have equated the fascination with mutilation, violence, and gore with sexual gratification. Cronenberg, of course, supplies another way of understanding Ducournau; few other filmmakers have investigated the connections between sex and the body’s destruction better than the Canadian auteur. So between Denis and Cronenberg, Ducournau’s film establishes her among good company.

What’s unique about Raw is that the cannibalistic themes never derail Ducournau’s interest in Justine as a character—her emergence into adulthood, sexual experimentation, and complex relationship with her sister. And then, the final scene finds Justine learning another twisted layer to her family’s history and experiences with cannibalism, and it’s an unsettling look at how her life will develop. And yet, the film rarely feels like a genre effort; it has little in common with the average vampire, zombie, or monster movie. Rather, Raw feels like a gristly and feminist examination of womanhood, complete with an unflinching look at the mortifying trials young women endure in college. The bloody trappings accent the story in expressive terms, enhancing their emotional power instead of indulging familiar horror tropes. Ducournau’s potent use of cannibalism captures the emotional violence and extremity of transitioning into adulthood in clever, sophisticated terms that cannot help but resonate, hunger for human flesh notwithstanding.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review