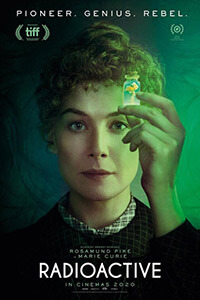

Radioactive

By Brian Eggert |

At once traditional and unconventional, Radioactive, the life story of scientist Marie Curie, follows a prescriptive biopic formula, but director Marjane Satrapi’s treatment contains a few inspired stylistic touches. Following the standards of a classy drama, the actors speak in English accents, though Curie, born in Poland as Marie Skłodowska, and later made a naturalized French citizen, spoke Polish and French. The film adopts a familiar structure, opening in Paris, 1934, when the elder Marie Curie, her hands blistered from radiation, falls from aplastic anemia after years of exposure to radiation during her research. As attendants rush her to the hospital, her life flashes before her eyes, starting in 1893, the year she meets Pierre Curie, which the screenplay by Jack Thorne considers the beginning of her story. The production’s costumes appear authentic, the wigs and false beards distracting. The characters give grand speeches about their feelings and ambitions. The science has been simplified for general audiences. Through it all, the film’s customary treatment of Curie proves almost embarrassing at times, until Satrapi injects something odd that feels delightfully out of place.

Satrapi is perhaps best known for her graphic novels, vivid memoirs of her youth in Iran during the Islamic Revolution. Both Persepolis and Chicken with Plums became dazzling animated films in 2007 and 2011, co-directed by Satrapi alongside Vincent Paronnaud. Her live-action work thus far has played by the same rules as her animated features. Look at The Voices (2015), featuring Ryan Reynolds as a disturbed man compelled to murder by people chattering in his head, and yet Satrapi maintains a masterful control of tone, balancing bloody humor and genuine empathy. And while her intentions for Radioactive remain clear, the screenplay doesn’t do the subject or the central performance by Rosamund Pike justice. Amidst messy flashbacks and flash-forwards, the film considers not only Curie’s life but the consequences of her work from our present historical perspective, in ways that reveal humanity as both curious and self-destructive. You could be forgiven for wondering whether the film believes that the world might’ve been better off without Curie’s science at all.

Based on Lauren Redniss’ book, Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie: A Tale of Love and Fallout, the film gets underway as Marie Skłodowska finds herself ejected from a male-dominated institution for her unconventional science and determination to find her own way, though mostly for being a woman. She bumps into Pierre (Sam Riley), a crystallographer, and her future husband, who later asks to work with her. He invents a microscope that measures electrical potential and will help in her research of uranium ore. She begrudgingly agrees to partner with Curie and, together, they discover two new elements, radium and polonium. “You have fundamentally misunderstood the atom,” she defiantly tells the faculty that ejected her from their facility in a proud moment. To be sure, there’s an undeniable air of female empowerment on display, along with several lines of dialogue that telegraph her significance as a figurehead in the women’s movement—delivered in such a way that speaks to modern viewers. It can feel soapboxy at times, though no less inspiring, even as the film plays like a highlight reel of notable events in her life.

Still, Marie and Pierre, soon married and teeming with children, make a discovery that leads to a Nobel Prize, but the consequences of their research ripple through time. When the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences decides to give Pierre their prize, he fights to have Marie’s name added, given that she spearheaded their research. Even so, Pierre gives an acceptance speech in which he questions whether humanity is ready for this knowledge—at which point Satrapi cuts to a flash-forward of the atomic bomb being dropped on Hiroshima. For every radioactive chocolate, toothpaste, beauty powder, and even a dance craze that stemmed from the Curies’ research in their lifetimes, the film also considers the sickness and destruction to come over the next century. Later, Satrapi cuts to Cleveland in 1957, where a boy receives radiation treatments for cancer, then the nuclear tests in Nevada in 1961, and the Chernobyl disaster in 1986. Though some evidence is shown that Curie helped save countless lives in World War I, where she introduces X-ray machines that help avoid needless amputations, the film seems unconvinced of Pierre’s insistence that they have done “more good than harm.”

Satrapi is unsubtle in a way that’s appealing in her animated films, or something intentionally over-the-top like The Voices, but her approach is questionable here. Her playful touches feel at odds with Radioactive’s basic biopic structure, as though they were added in post-production to enliven the otherwise straightforward treatment. Note the CGI visualizations of chemical processes and other curious flourishes, such as the animated shadows that float to the stars after Marie and Pierre sleep together. The score, courtesy of Evgueni and Sacha Galperine, is equally playful, using Atomic Age theremin music and synthesizers stuck in an ‘80s riff, as well as elements of classical music. Satrapi’s cinematographer, Anthony Dod Mantle, renders most scenes with the edges of the frame either darkened like an iris shot in a silent film or alternately out of focus like an old photograph—as though Satrapi fought the urge to adopt the now-chic Academy ratio. Curie’s visits to an expressive dancer and psychic medium offer additional opportunities for wild visuals; though, there’s nothing more surreal than Curie sleeping with a bottle of glowing radium night after night.

Curie’s discoveries have led to advances in medical technology, but they have also caused immeasurable death and fear. The problem, the film resolves, is humanity. “Throw a stone in water. The ripples you cannot control,” someone rationalizes later, tidying up any complex questions about scientific ethics. Along with this dull solution, the viewer can feel Satrapi wanting to push Radioactive further into a more expressive or post-modern style. Except, for every delightfully peculiar fingerprint she leaves, she also delivers several more obligatory moments—the usual smattering of lofty speeches, standing ovations, love affairs, and montages that skip over decades of Curie’s life near the end. The film is trapped between the biopic archetype and something more inventive, and its failure to commit to either mode leaves it somewhat unsatisfying. Pike, of course, is excellent, playing another Great Woman after Ruth Williams Khama and Marie Colvin. But Radioactive wrestles with its subject and form, and not always in productive ways.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review