R.M.N.

By Brian Eggert |

This film was screened at the 42nd Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival. For the full lineup of films available between April 13-27, check out the schedule here. The film arrives in theaters everywhere on April 28, 2023.

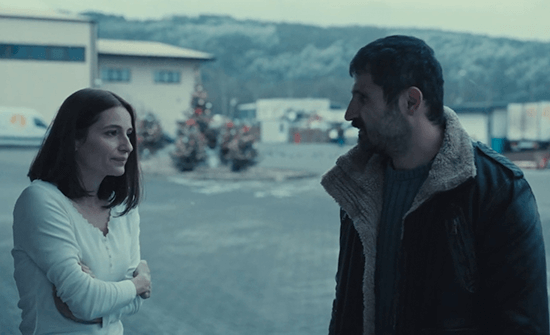

Cristian Mungiu’s R.M.N. opens and closes with parallel scenes where a character sees something strange in the woods. What they see might be described as hallucinations, projections, delusions, or premonitions, but their basis in reality is tenuous. First, a young boy, Rudi (Mark Blenyesi), walks amid fallen leaves in a skeletal, autumnal forest on his way to school. Then he stops in his tracks. He sees something ahead, outside of the frame. Spooked, Rudi darts in the opposite direction. Whatever Rudi saw, he cannot and will not say. The trauma renders him temporarily mute. Later, Rudi explains what he saw, and later still, the image seems to materialize into reality. In the final staggering shot of the film, Rudi’s father, Matthias (Marin Grigore), heads into the forest and sees something uncanny. Except this time, Mungiu shows the viewer what Matthias sees. The tension between what one perceives and how that’s determined by their political, religious, and ethnic identities and anxieties, remains at the center of the Romanian filmmaker’s latest, a portrait of a Transylvanian village at odds with Sri Lankan migrant workers hired to work at a local bakery. Profoundly moving and unshakable afterward, its scope reaches beyond the intimate, personal dramas Mungiu usually directs and provides a stark allegory that resembles any nation, Romanian or otherwise, and becomes a sweeping portrait of humanity at its worst.

Mungiu based the film on a real-life town hall meeting in Transylvania, which was recorded and can be viewed online, assuming you speak Hungarian. His version of the meeting unfolds over a 17-minute unbroken shot, the film’s bravura centerpiece of unblinking realism, with two dozen speaking roles, a crowd of extras, and overlapping dialogue in multiple languages. The scene involves the village mayor overseeing a public debate, where the locals present their cases for allowing the Sri Lankan bakers to stay or forcing them out of town, while the bread factory owner and manager defend their choice to hire workers from the South Asian country. Fittingly, given the title, it’s a scene that clarifies everything under the surface, both with the town and between the two main characters. Indeed, R.M.N. refers to the Romanian term for nuclear magnetic resonance (rezonanta magnetica nucleara), the scientific technique whereby atomic nuclei absorb high-frequency radio waves when subjected to a magnetic field—a process by which MRI machines apply a combination of radio waves and magnetic fields to capture multi-layered images of the body. In terms a layperson can understand, Mungiu uses this as a metaphor for bringing the hidden into light with the right agent or circumstance.

The film swells before the town hall sequence, set about two-thirds into the film. Along the way, Mungiu adds precise brushstrokes to a portrait of a community with a complex national history, marked by cultures of various backgrounds, whose relationships have evolved over time. Mungiu’s entry point is Matthias, who works in a German slaughterhouse until a supervisor derides him as a “fucking lazy Gypsie.” He responds with an immediate, shocking act of violence, prompting him to evade authorities and leave the country for his home in Romania. There, Matthias visits his estranged wife Ana (Macrina Bârlădeanu) and their son Rudi, believing that Ana is coddling the child’s sensitive nature. Matthias intends to force Rudi back into the woods to confront his fear. Elsewhere, Matthias visits his ailing sheep-farmer father, Papa Otto (Andrei Finți), who needs an MRI, and whose livestock have been going missing, possibly eaten by the local bear population. And he connects with Csilla (Judith State), rekindling a former love affair, despite their opposing politics and attitudes toward migrant workers—ironic, given Matthias’ recent experience in Germany and his status as an ethnic “mongrel,” according to some local men.

The film swells before the town hall sequence, set about two-thirds into the film. Along the way, Mungiu adds precise brushstrokes to a portrait of a community with a complex national history, marked by cultures of various backgrounds, whose relationships have evolved over time. Mungiu’s entry point is Matthias, who works in a German slaughterhouse until a supervisor derides him as a “fucking lazy Gypsie.” He responds with an immediate, shocking act of violence, prompting him to evade authorities and leave the country for his home in Romania. There, Matthias visits his estranged wife Ana (Macrina Bârlădeanu) and their son Rudi, believing that Ana is coddling the child’s sensitive nature. Matthias intends to force Rudi back into the woods to confront his fear. Elsewhere, Matthias visits his ailing sheep-farmer father, Papa Otto (Andrei Finți), who needs an MRI, and whose livestock have been going missing, possibly eaten by the local bear population. And he connects with Csilla (Judith State), rekindling a former love affair, despite their opposing politics and attitudes toward migrant workers—ironic, given Matthias’ recent experience in Germany and his status as an ethnic “mongrel,” according to some local men.

Meanwhile, Csilla manages the bread factory, reporting to its owner Mrs. Dénes (Orsolya Moldován). The factory requires five more workers to secure a European Union grant. Ads have run for weeks in the town but have been unsuccessful in attracting locals to work for minimum wage; rather, locals seek more lucrative opportunities abroad. So Csilla legally hires two Sri Lankan workers with plans to hire three more to secure the grant. But the arrival of two migrant workers, followed by a third, sets the town afire (quite literally later on) with racist scorn, followed by a boycott of the factory’s bread. “We’re fine with them if they stay in their country,” says one vocal detractor. Those opposed to the workers appeal to the local reverend, who, while claiming to Csilla that he’s not taking sides, defends their point of view, arguing, in most un-Christian terms, “Everyone has their own place in the word.” At the same time, townspeople prepare a petition to force out the Sri Lankan workers, who feel unsafe after death threats appear on a hate-fuelled Facebook group. Csilla tries to calm them by securing a place to stay and having dinner with them one night, but their modest moment of peace is interrupted by a sudden burst of intolerance.

Historically, Transylvania is a region that has shifted borders and national identities many times, making nationalism a sticky notion. One character in the film notes that Romania has been “squeezed” at all sides but survives, its borders fluctuating. Doubtless, Mungiu chose the region to emphasize the illusory and shifting nature of nationalistic identity and, therein, its impermanence and the futility of attempting to preserve it. The dynamics of ethnicity in Romania underscore the theme, apparent in the various languages represented (Romanian, Hungarian, German, English, and French). Although these languages were reportedly distinguished in some festival screenings by different subtitle colors, the US version distributed by IFC Films uses white subtitles, requiring either an ear for languages or the acceptance that some of these details will be lost. For instance, with Hungarian representing a minority in Romania, Hungarian characters opposed to the migrant workers might denote a hypocrisy over their fervor, just as both groups rally against the nomadic peoples of Europe.

As with most of Mungiu’s work, his R.M.N. script can seem opaque, especially in the beginning, when he’s establishing characters and detailing the overarching conflicts in the unnamed town (actually Rimetea, a Transylvanian commune). But his method of ratcheting suspense is patient, a familiar trait of his previous work. The film arrives seven years after Mungiu’s last film, Graduation (2016), which earned him the Best Director Award at the Cannes Film Festival. And like that film, the director once again teams with cinematographer Tudor Vladimir Panduru, whose spare, probing camerawork never overemphasizes or underlines; instead, the frame maintains an observational distance, with visual flourishes denoted in the stark compositions and gray-blue color palette that evokes the bleak sociopolitical backdrop. Mungiu and editor Mircea Olteanu keep a deliberate pace, never resorting to hyperbolic thrills for their own sake. R.M.N. is sharp and strategic in its execution. If the film rarely has the emotional immediacy of Mungiu’s Palme d’Or-winning masterpiece 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007), it contains rich intertextual and symbolic underpinnings that will reward a second and third viewing.

As with most of Mungiu’s work, his R.M.N. script can seem opaque, especially in the beginning, when he’s establishing characters and detailing the overarching conflicts in the unnamed town (actually Rimetea, a Transylvanian commune). But his method of ratcheting suspense is patient, a familiar trait of his previous work. The film arrives seven years after Mungiu’s last film, Graduation (2016), which earned him the Best Director Award at the Cannes Film Festival. And like that film, the director once again teams with cinematographer Tudor Vladimir Panduru, whose spare, probing camerawork never overemphasizes or underlines; instead, the frame maintains an observational distance, with visual flourishes denoted in the stark compositions and gray-blue color palette that evokes the bleak sociopolitical backdrop. Mungiu and editor Mircea Olteanu keep a deliberate pace, never resorting to hyperbolic thrills for their own sake. R.M.N. is sharp and strategic in its execution. If the film rarely has the emotional immediacy of Mungiu’s Palme d’Or-winning masterpiece 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007), it contains rich intertextual and symbolic underpinnings that will reward a second and third viewing.

Indeed, Mungiu plays a clever game with what he shows and conceals. R.M.N. is a film where the viewer must question the visual information given to us more than in any Mungiu film. For example, when Matthias attempts to convince Rudi that the woods are safe, he points out a bear in the distance and fires his shotgun in that direction. Mungiu never reveals whether there’s really a bear or Matthias wanted to demonstrate to his son the power of humanity over Nature with a loud boom. He also teaches Rudi how to fight (“It’s easy. Just don’t feel pity.”) and boil fresh water at a campsite. However, Mungiu is well-versed in visual symbolism, despite his stripped-down aesthetic and outward appearance of realism, as evidenced in the fish tank imagery throughout 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days. This is also true of R.M.N., which explores the relationship between humans and animals as a parallel for how people discriminate against others, seeing them as sub-human. From the opening moments with Matthias in the slaughterhouse to his greeting at the Romanian village by a sign that reads “Beware the Wild Animals,” to the French environmental worker there to monitor the bear population, Mungiu’s film considers animals’ role in the local population.

Long before so-called civilization was around, wild animals occupied the land freely. But now they’re farmed, butchered, or hunted when seen on cultivated property with the same discrimination applied to the Sri Lankan workers. Mungiu goes even further to emphasize this point, and its extended metaphor, with the uncanny last shot, which finds him breaking from reality altogether in an eerie sight ripe for multiple interpretations. Viewers will be looking for parallels and meaning, like Matthias scanning through the results of Papa Otto’s MRI on his phone, trying to put together how each image connects with the next. Of course, Mungiu isn’t speaking exclusively about ethnic conflict in Romania; he’s making broader observations about human short-sightedness and bigotry that could be compared to any ethnic confrontation throughout the world. Chances are, watching the film will bring to mind countless specific cases of intolerance and groupthink that reveal people’s capacity to exclude and become violent toward difference on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender identification, or any number of arbitrary reasons. With discerning observations and intricately conceived analogies involving atoms and Animalia, R.M.N., one of the year’s best films, uses specific ethnic divides to expose raw and universal truths about humanity.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review