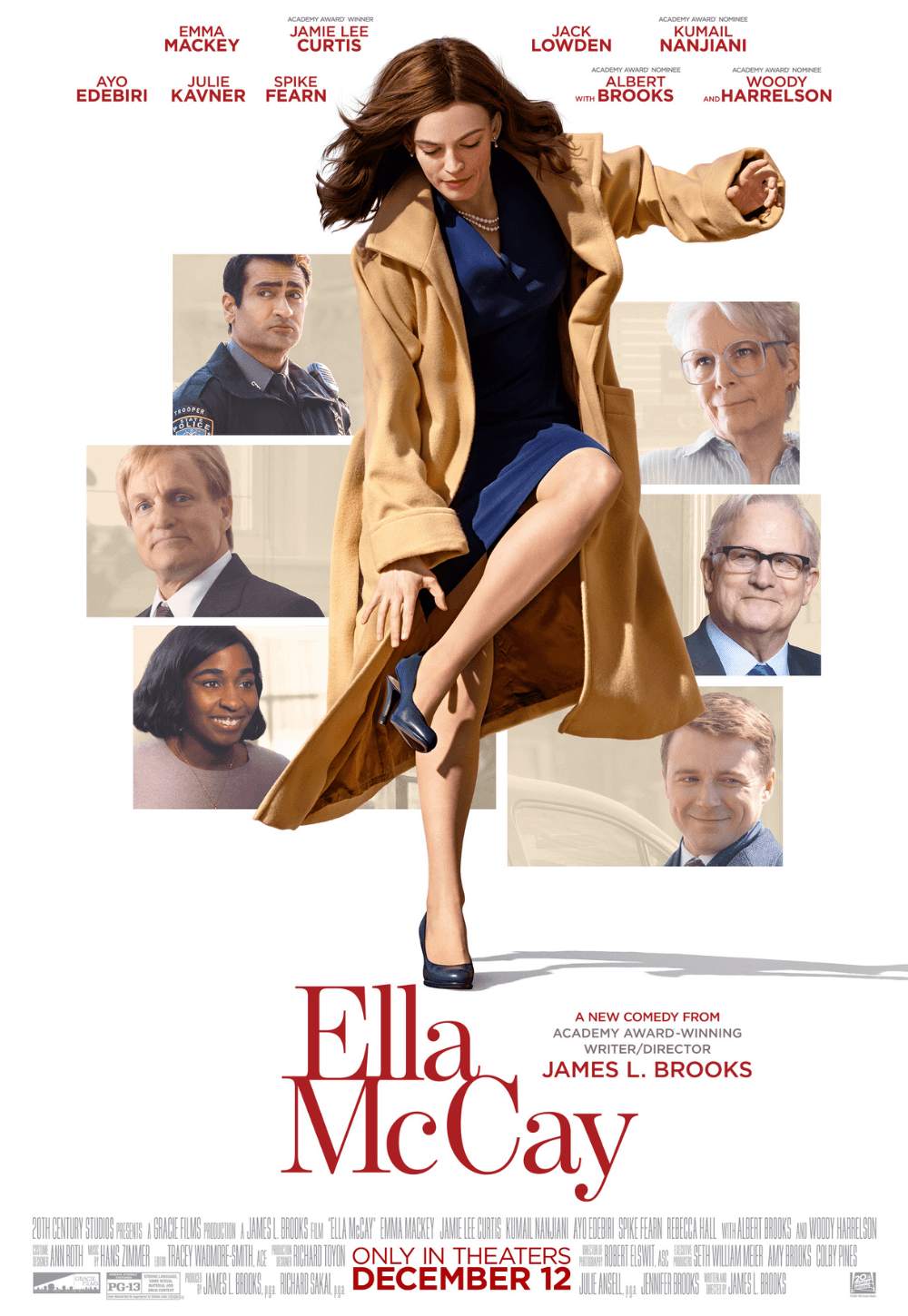

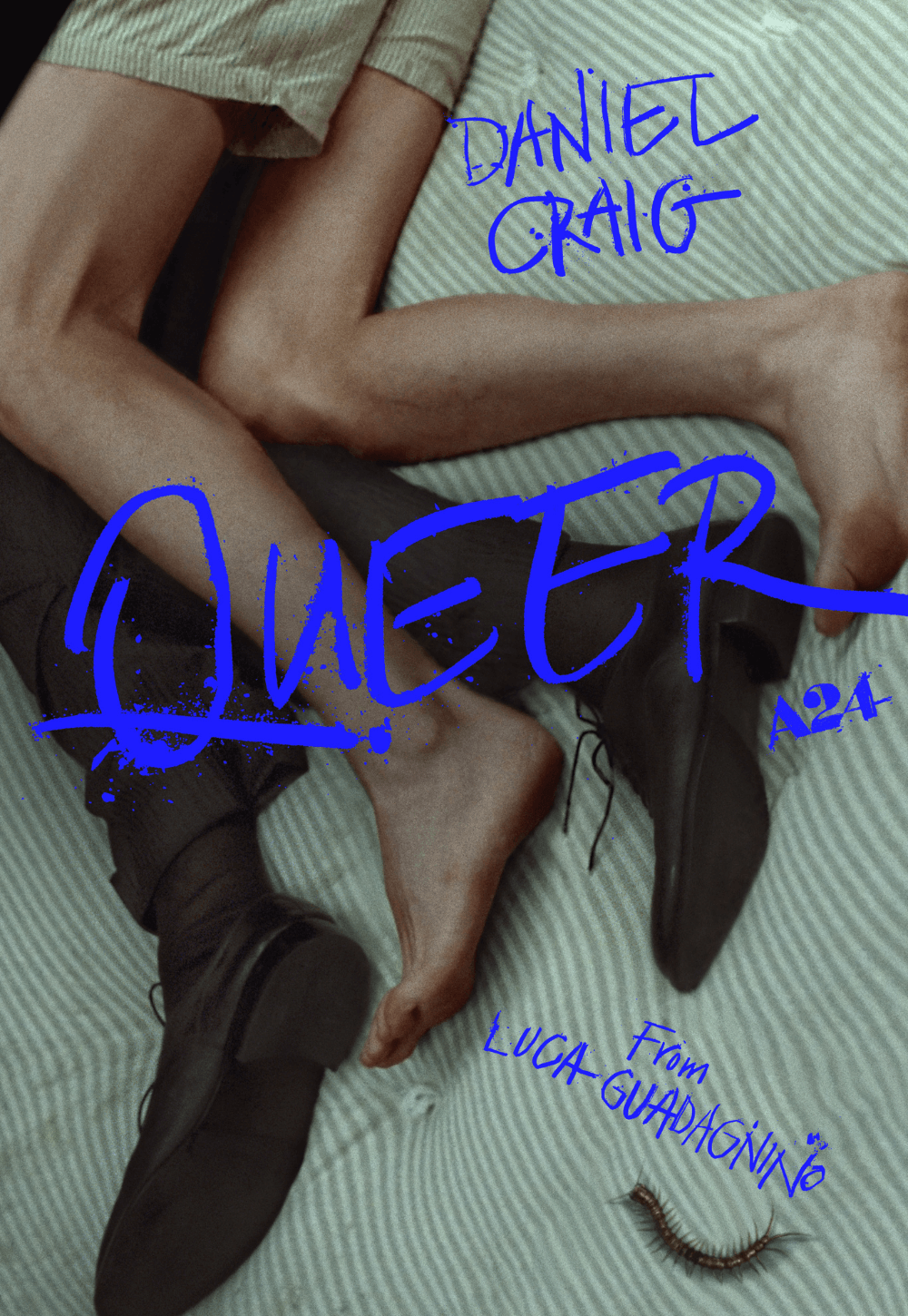

Queer

By Brian Eggert |

An expatriate in Mexico City, the perpetually displaced Bill Lee sits at a bar, downing shots and muttering to himself. The revolver tucked into his belt is hidden by the dingy white linen suit he’s been wearing for days. A layer of sweat covers his skin. His eyes appear glassy and tired. Most people take one look at him and immediately recognize he’s a junkie. Although Bill drinks relentlessly and maintains a heroin addiction, he needs a different kind of fix, rooted in desire. His reckless yearning has left him desperate and searching. This is not how we’re used to seeing Daniel Craig, who sets aside his popular James Bond and Benoit Blanc personas to remind us that he’s an actor of incredible range. In Queer, Craig plays the fictional counterpart of William S. Burroughs, author of the 1985 novella that director Luca Guadagnino has wanted to bring to the screen since his youth. From casting Craig against type to layering the film with anachronistic music and surreal hallucinations informed by Burroughs’ later work, Guadagnino’s dreamlike adaptation, along with Craig’s outstanding performance, capture the wanton desire fueling one of Burroughs’ most personal characters.

Burroughs wrote Queer under extreme emotional strain. He had lived in Mexico City since 1949, having fled there to escape legal trouble over a drug possession rap in Louisiana. During his time in Mexico, the Beat Generation writer lost himself to drugs and drink. His life took a further downswing in 1951 when he accidentally shot his common-law wife, Joan Vollmer, in the head during their usual “William Tell” routine for parties. Sometime later, Burroughs met and fell in love with Lewis Marker, a former Navy man. The two bummed around the capital city for months before, in 1953, they took an expedition to South America. Burroughs sought to explore the hallucinogenic plant yagé (ayahuasca), which the locals used in their rituals for its rumored telepathic properties. He documented this journey in letters to his friend Allen Ginsberg, published in the 1963 book The Yage Letters. But Marker soon grew tired of Burroughs’ addiction, along with his erratic and obsessive behavior; he abandoned Burroughs in the Amazon. Reeling from his losses, Burroughs wrote Queer, though it went unpublished for thirty years and, even then, remained unfinished.

In the book and Guadagnino’s film, Burroughs is presented as William Lee, the unabashedly autobiographical alter ego he uses in many novels. The thin disguise has led scholars and readers to search for links between the two, and the connections aren’t difficult to find. And Guadagnino’s film wouldn’t be the first to explore how Burroughs blended his life and fiction. Most famously in David Cronenberg’s adaptation of Naked Lunch (1991), the writer-director wove aspects of Burroughs’ life into the film, intermingling the author and avatar. For Queer, Guadagnino and screenwriter Justin Kuritzkes hew closer to the source material. Guadagnino had been fascinated by the book since his teen years. While already exploring themes of maddening desire during Challengers, he encouraged Kuritzkes to adapt the book and complete the story as Burroughs never did—the text ends with Lee and the fictionalized version of Marker, Eugene Allerton, in the jungle, unable to get their hands on the yagé plant. Kuritzkes fills in the ending of Queer with notes and flourishes from Burroughs’ life and work; otherwise, the film remains focused on its theme of almost irrational desire.

Even while the uninitiated viewer could watch Queer and appreciate Bill’s acute yearning, racing from one bar to the next, looking for a hookup or a hit, Guadagnino’s film rewards those with some context about the author, his work, and his life. It might be downright impenetrable for some. The film finds Bill in a routine at various Mexican nightspots, where he need not worry about the sociopolitical risks of picking up anonymous men and accompanying them to hotels. In a sequence set to “Come As You Are”—the second Nirvana song in Queer after Sinéad O’Connor’s “All Apologies” cover over the opening credits—he spies Eugene (Drew Starkey) during a cock fight. Despite his infatuation, this ravenous character looks bashful in Eugene’s presence. After spotting him, Bill launches into a tenuous courtship with Eugene, who can seem aloof and uninterested, which, of course, makes him all the more desirable. Their eventual affair unfolds in intimate encounters, where not even Eugene’s recent vomiting will dissuade Bill. But he never quite manages to get Eugene for himself; despite regular encounters with Bill, Eugene can be distant. This is maddening to Bill, whose adoration is tantamount to covetousness.

Segmented into three chapters, followed by an epilogue set two years later, Queer finds Bill looking to unleash his telepathic sensitivities with yagé—perhaps to understand Eugene, perhaps to understand himself. His desire to know himself and Eugene is central to the film, evidenced when Bill and Eugene see Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus (1950) together in the cinema—a film tied up in the notion of an artist’s introspection, signified by a motif of mirrors and reflections. When Bill convinces Eugene to join him in South America to find some ayahuasca, he isn’t hoping for another recreational drug but to unlock his mind and make a deeper connection with Eugene. When they finally locate their source in the jungle—Dr. Cotter, played by Leslie Manville, whose character is a man in the book—they find her under a layer of grime, with greasy hair and rotten teeth. She carries a gun, points it unsparingly, and keeps a pet sloth. It’s an incredible transformation by Manville. Despite her haggard appearance, she sizes up Bill and Eugene quickly. They are both afraid. The former fears his open-hearted desire; the latter dreads exposure in a world that doesn’t accept him and compels him to repress his feelings.

Craig captures Bill’s internal struggle beautifully, using his swaggering masculinity as Bill’s defense against a world that has notions about how a man should be. This armor comes with specific terminology: “I’m not queer,” Bill claims. “I’m disembodied.” Bill even deems his proclivities a “curse” that makes him a “pervert” and a “sex monster,” embracing the terms society might give him to ironic effect. Burroughs, too, rebelled against labels. Still, Bill cannot deny his desire. Quiet scenes of Bill and Eugene together find him imagining his hands, shown as transparent phantoms, reaching to brush back Eugene’s hair or caress his face. Their intercourse alternates between passion and carnality, yet it allows for moments of laughter in their pleasure. If Bill cannot accept being called gay, his love of Eugene writhes like a loose electrical wire in his brain, leaving him almost panicked with raw feelings and the need to have them returned—in the same way he needs a fix. It’s an all-consuming obsession to maintain that love. While Starkey plays guarded uncertainty well, Craig’s performance is a complete embodiment, informed by both Burroughs’ severe exterior and William Lee’s vulnerability.

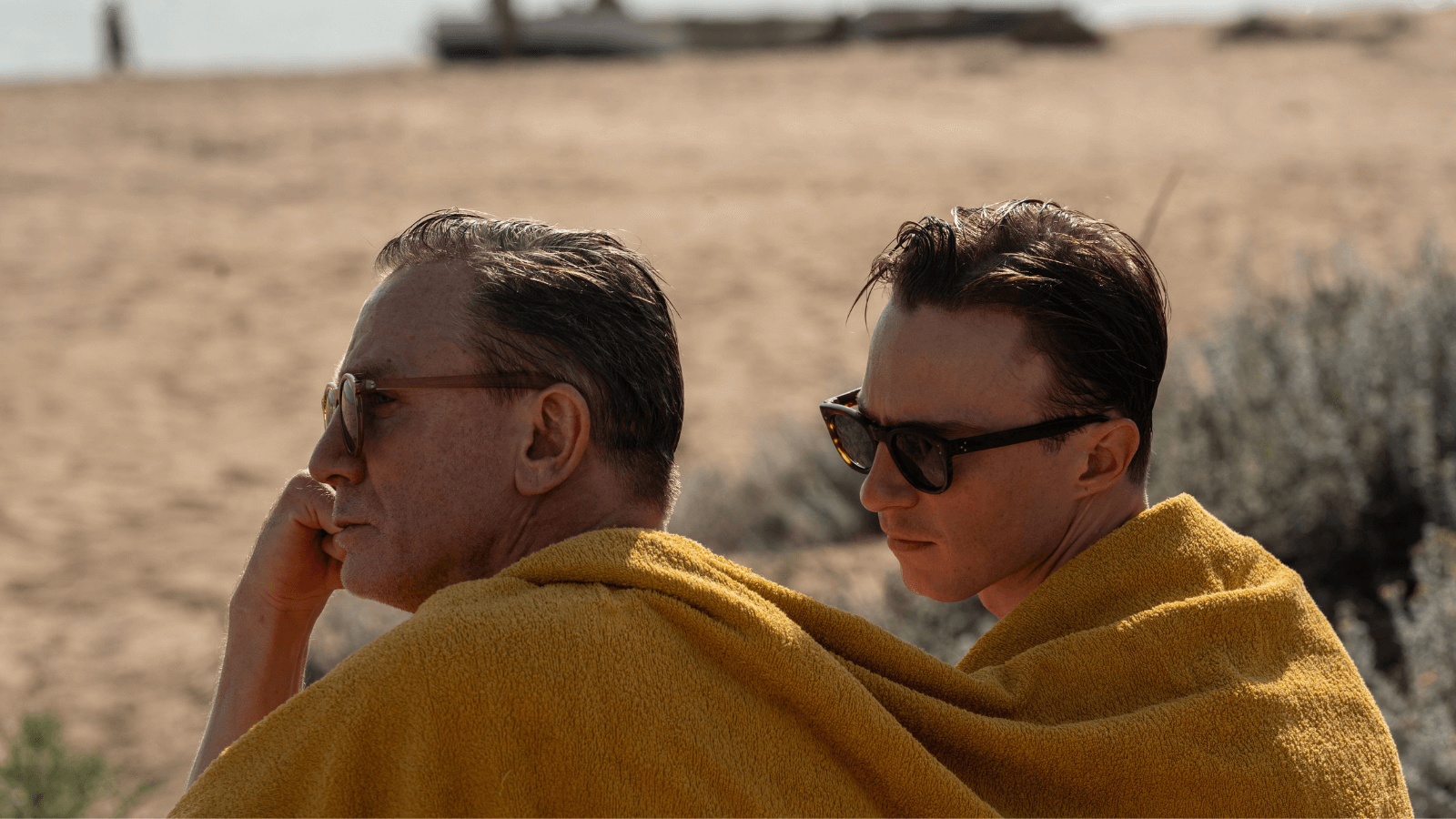

Guadagnino echoes this interplay of artificial surfaces and outsiders in his execution. Note his soundtrack, populated by nonconformist, defiantly independent artists whose music and personas align with the film’s so-called social misfits: O’Connor, Nirvana, Prince, and New Order. Much like Cronenberg’s approach to Naked Lunch, Guadagnino presents his Burroughs adaptation in a false, closed-off world, mostly shot at Cinecittà Studios in Rome. There, production designer Stefano Baisi built versions of Mexico City, Quito, and the South American jungle. Guadagnino embraces this conspicuous artifice to show that society is just a surface. When Bill and Eugene travel, the cars and planes look like die-cast models; backdrops appear rendered with CGI, lending the setting a painterly yet intentionally faux quality. Likewise, Jason Schwartzman plays Joe Guidry, the fictionalized version of Alan Ginsberg, in an unconvincing suit that puffs the actor up to resemble Ginsberg. More earnest but leaning into Bill’s emotional state is the score of mysterious, winding notes by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross.

Few filmmakers portray sensory experiences as thoughtfully and passionately as Guadagnino. His treatment of bodies and sensations often results in phantom perceptions, from the mouth-watering cuisine and lovemaking in I Am Love (2010) and Call Me By Your Name (2017) to the curious blend of young love and cannibalistic hunger driving Bones and All (2022). No one working today quite understands involuntary physical responses better. He ties these feelings into Queer through cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom’s fluid camerawork that captures the physical aura of these characters, while zipping through Bill’s life with ever-moving bravado and dexterous energy. We can almost smell their essence, but instead of a rank aroma, Guadagnino sees the appeal for Bill and captures it for the audience. After Bill and Eugene take ayahuasca, the ensuing hallucinations have the same physicality, albeit torn from deep in their subconscious. And while Marco Costa’s calculated, efficient editing often has a staccato effect to minimize transitional moments, Guadagnino knows when to hold a shot. Consider how he pans to windows to look outside during love scenes, underscoring how two people have connected in a vast world.

One unforgettable, extended shot finds Bill cooking heroin and preparing the needle. After shooting up, the camera lingers on Bill in his solitude, which plagues him. Craig conveys his character’s restlessness and disquiet with perfect fidelity. In this and other moments like it, the star and Guadagnino deliver a character who feels so much yet struggles to articulate or satisfy those emotions, leaving him unresolved. Similarly, the filmmakers had to invent a conclusion to Burroughs’ book. Guadagnino and Kuritzkes take the material to its natural outcome, informed by the author’s mind-altered imagery—an ayahuasca odyssey of what-the-fuck visuals, leading to a head-spinning finale that veers into psychedelia. It’s all obscure, but somehow it’s also readable. The final section might lose some viewers by venturing into Lynchian dream imagery, but Queer’s ending reveals that this episode of Bill’s life, and therein Burroughs’, never led to closure. That lasting love and desire remained with him until his final days, like a wound that never healed into a scar. Queer captures this dreadful ache with one of Craig’s best performances yet, while Guadagnino’s raw, audacious, exposed-nerve filmmaking reminds us why he’s among today’s greatest directors.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review