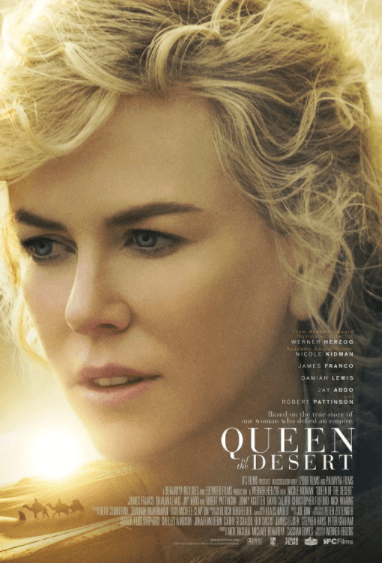

Queen of the Desert

By Brian Eggert |

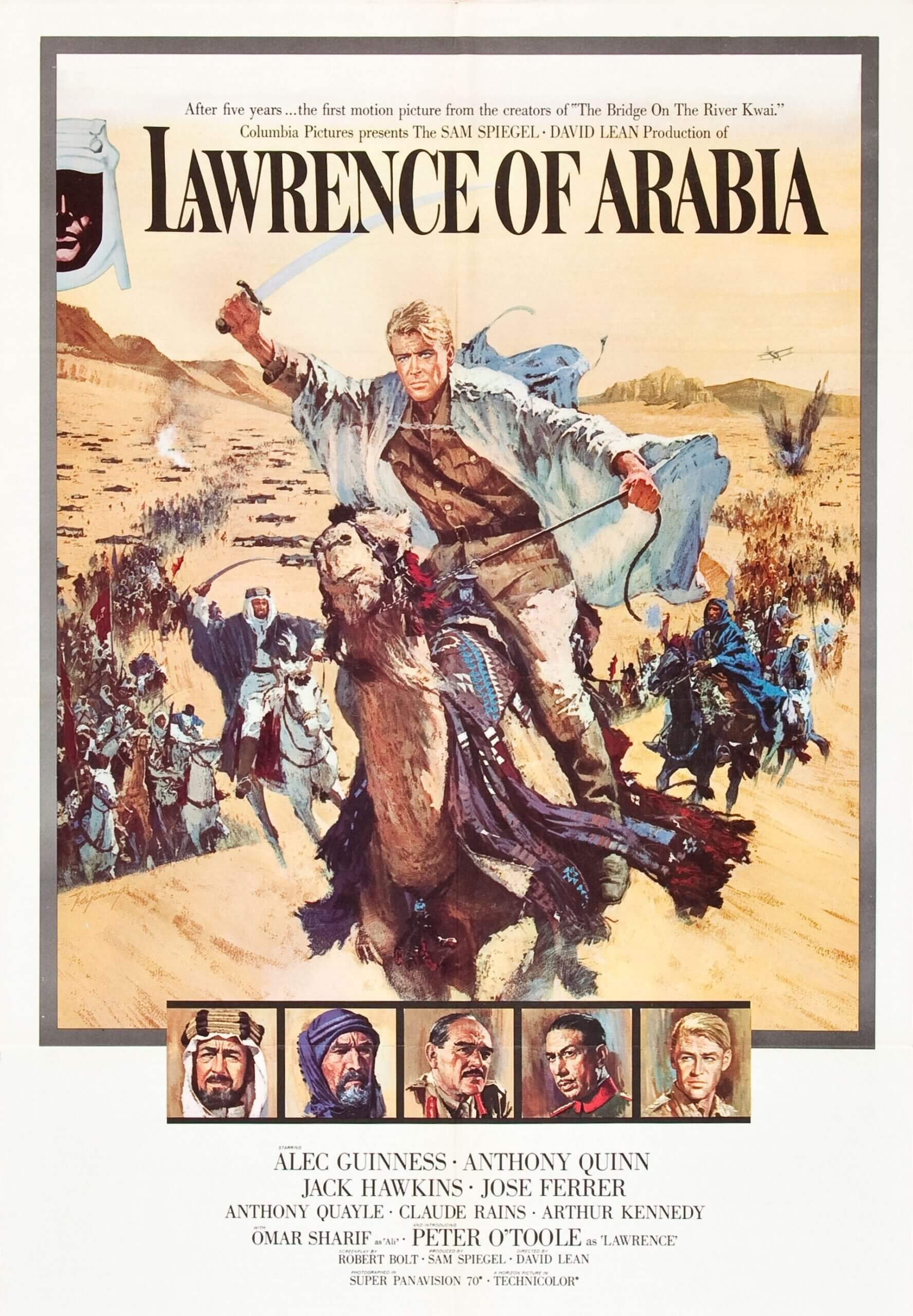

A scene in the middle of Queen of the Desert finds Gertrude Bell, the British explorer of the Ottoman Empire, being asked to eat the head of a lamb as the honored guest of the Sheikh. Undoubtedly, the real Bell would have observed the custom and felt honored to chomp into some lamb face-meat. And, in fact, the film’s version of Bell, as portrayed by Nicole Kidman, impliedly eats the lamb head in this scene, although the action occurs off-camera. One can suppose that Kidman refused to ingest actual lamb for the scene; then again, perhaps the lamb head was not actual food but rather a prop. Either way, the film does not show the meal, marking a rare moment of wanting authenticity from director Werner Herzog, one of today’s finest filmmakers. Queen of the Desert has been made not in the Herzogian tradition of mad people who venture into the wilds of Nature to face the sublime; rather, the German maverick tries something decidedly more Hollywood by evoking David Lean’s romantic epics, most palpably Lawrence of Arabia—albeit more conventional.

After years of making documentaries and fiction films about people reconciling their place in the natural world, it’s not difficult to understand why Herzog was drawn to his subject. Gertrude Lowthian Bell (1868-1926) carved out her own place in the world at an early age, being one of the first women allowed to attend Oxford to study history. Bored with the dull life of a British woman, she soon traveled to the former Ottoman Empire, visiting regions and cities across Arabia that few Western women of the time had ever experienced: Syria, Persia, Mesopotamia, and countless others. She became fluent in Arabic and other languages, earning a respected place among the divided tribes of the Arabian world, later earning her the relegated title of “the female Lawrence of Arabia”. During and after World War I, Bell worked alongside Churchill to construct British imperial policy in the Middle East and divvy up the Ottoman Empire. During her time in Arabia, she served as an author of archaeology, cartography, and documented her travels, focusing largely on the preservation of relics from the Babylonian Empire. Her influence was formative, above all in modern Iraq, where she reportedly stands as the example against which all western women are contrasted.

Herzog tells her story from an original screenplay. He was backed by several independent producers (Benaroya Pictures, H Films, Evolution Entertainment, and others) for a shoot in England, Jordan, and Morocco on a budget of around $36 million. The relatively brief shoot (December 2013 to March 2014) required few special FX or action sequences, and the finished film screened the following year at the 2015 Berlin Film Festival. After some unfavorable early reviews, the film’s several production companies kept Queen of the Desert languishing in distribution negotiations for over a year, until finally IFC picked up distribution rights for a limited theatrical release and VOD debut. A similar series of delays and finagling among producers and distributors found another recent Herzog film, Salt and Fire, long-delayed and finally released with a whimper just a week before Queen of the Desert. Neither film shows Herzog at his best, but even the worst efforts from great filmmakers are interesting failures.

The uneven quality of the film is apparent from the outset. Kidman seems oddly cast in early scenes where a restless, thirtysomething Bell pleads with her parents (David Calder, Jenny Agutter) to send her abroad. She ends up at the British embassy in Tehran, where she meets Henry Cadogan (James Franco), a playful huckster with a deep affection for Arab culture. Their endearing courtship unfolds in classical style with grand gestures—such as the two pieces of a halved coin of Alexander the Great shared between them as a remembrance—but it’s a doomed romance. In episodic fashion, Bell moves on to an encounter with T.E. Lawrence (Robert Pattinson) and later exchanges impassioned letters with Maj. Charles Doughty-Wylie (Damian Lewis). For the duration of the film, she must repeatedly defend her place as a woman among stodgy British men with low views of female independence, and moreover, among the Arab people who are equally surprised to find an intrepid and intelligent woman in their midst.

The uneven quality of the film is apparent from the outset. Kidman seems oddly cast in early scenes where a restless, thirtysomething Bell pleads with her parents (David Calder, Jenny Agutter) to send her abroad. She ends up at the British embassy in Tehran, where she meets Henry Cadogan (James Franco), a playful huckster with a deep affection for Arab culture. Their endearing courtship unfolds in classical style with grand gestures—such as the two pieces of a halved coin of Alexander the Great shared between them as a remembrance—but it’s a doomed romance. In episodic fashion, Bell moves on to an encounter with T.E. Lawrence (Robert Pattinson) and later exchanges impassioned letters with Maj. Charles Doughty-Wylie (Damian Lewis). For the duration of the film, she must repeatedly defend her place as a woman among stodgy British men with low views of female independence, and moreover, among the Arab people who are equally surprised to find an intrepid and intelligent woman in their midst.

Queen of the Desert resembles Lawrence of Arabia in many ways, including our questions about what drives the protagonist. Whereas David Lean weaved that enduring question (“Who are you?”) into the fabric of his nearly 4-hour masterpiece, Herzog leaves the answers to the audience, quite unsatisfyingly so. Without various kernels in the drama to help us understand Bell, Kidman’s performance feels lifeless. The character travels from one life event to the next without reason, her romances feeling basic and uncomplicated—a far cry from the love affairs in the similar setting of The English Patient. Somewhere between the script and the performance, the film fails to provide a way to understand Bell beyond her admiration for Arabia. Herzog also sidesteps any postcolonial commentary that may put the story into a more dynamic historical context. Of course, Lawrence of Arabia also avoided a critical postcolonial view; but in 1962, the outcome of the decisions made by the British imperialists and Arab leaders was less apparent than today. Then again, Herzog has never been about complicated political views—his films are existential and feeling.

All the while, the film’s conspicuous casting lingers after most scenes, as watching Kidman paired alongside Franco seems strange in this context. First, the age disparity is distracting onscreen, and by no fault of Kidman’s. To be sure, any preoccupations about Kidman’s age-appropriateness can be justified and corrected by biographical and Hollywood history. After all, Bell was well into her forties by the time of her romances with Cadogan and Doughty-Wylie, who were about her same age, so Kidman was an apt choice. It’s Franco who was miscast (he replaced a more fitting Jude Law). If anything, Herzog has reversed the usual trend of Hollywood’s youngest starlets getting the best roles by casting an age-appropriate performer in the lead; whereas Franco, with his effortlessly modern sensibilities, looks far too boyish and cartoonish to play a British romantic. And while it’s refreshing to see a May-December romance with an older woman and a younger man, Franco’s persona doesn’t fit this period setting.

The production looks epic-sized, with Herzog’s longtime cinematographer Peter Zeitlinger capturing the mystique and Orientalized allure of the desert in long, unbroken takes and pensive views of the landscape. Klaus Badelt’s score borrows more than a few cues from Maurice Jarre’s iconic score to Lawrence of Arabia, which is par for this otherwise conventional film from a director that is anything but. Indeed, it might be impossible for Herzog to make a normal film well, and so the result is rather slow and empty. With Queen of the Desert, the director fails to find a dramatic framework through which to view his subject. Admittedly, Bell’s life of wandering around the Middle East on various archeological pursuits does not have an inherently cinematic narrative. And what’s worse, Herzog rarely takes more than a week or so to write his screenplays. For all his attempts at embracing and paying homage to Hollywood convention here, the fit seems incongruous and the treatment oversimplified, despite the material containing themes ingrained in Herzog’s body of work.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review