Public Enemies

By Brian Eggert |

Director Michael Mann’s Public Enemies reaches into the glamorous 1930s-era gangster genre to score another symphony of crime on par with his earlier work. Rather than creating his own characters, Mann meticulously recreates the lives of several iconic figures in true crime. Bryan Burrough’s text Public Enemies: America’s Greatest Crime Wave and the Birth of the FBI, 1933-34 provides historically accurate source material for Mann to reformat. Though Burrough’s book thoroughly examined the lives of several Depression-era criminals like Bonnie and Clyde, Baby Face Nelson, and Alvin Karpis, Mann streamlines and cleverly dramatizes the episodic tome into a tale primarily about bank robber John Dillinger.

As he did with Heat, Mann explores a saga-sized cops and robbers scenario with two grand actors filling the principal roles. Johnny Depp plays Dillinger, the folk hero criminal of the 1930s. Christian Bale plays Melvin Purvis, poster child for the Chicago-based FBI task force dispensed by J. Edgar Hoover (Billy Crudup) to catch Dillinger. In the first scenes, Purvis guns down Pretty Boy Floyd (Channing Tatum) and earns his Chicago appointment in consideration of his kill. Hoover wants Dillinger dead and instructs Purvis to “take off the white gloves” to get him. Backed by men inexperienced in such tactics, Purvis stumbles after Dillinger, who, on his raid of bank robberies, gathers public support and glorification.

The dialogue says it all, exuding airs of James Cagney gangster pictures, like, of course, Public Enemy and White Heat: “I want everything. Right now.” Dillinger says these words to a pretty coat-check girl, Billie Frechette, who doubts her suitor’s fancy. “I like baseball, movies, good clothes, fast cars… and you,” he says. “What else you need to know?” Somehow, never mind why, she’s wisped away by Dillinger despite his well-publicized crime spree, and they become star-crossed lovers destined to be brief but immaculate. Knowing full well going into the picture that Dillinger is eventually shot to death by FBI agents makes their impulsive affair all the more passionate for the viewer, yet it’s also shrouded in fatalism.

Mann utilizes digital photography to shoot and edit as fast-and-loose as Dillinger lived, and for a lower cost than traditional film stock. Using this time-efficient and budget-friendly choice in his previous films Collateral and Miami Vice gave those contemporary-set stories an appropriate real-time experience, grainy like a home video, supplying his audience the sense that they’re observers in the moment. Here, in a 1930s period piece, Mann’s choice of digital works against the dramatic consistency of his film. Handheld camerawork on digital loses the gloss and visual smoothness of what more refined cinematography can bring. Instead, faster camera movements in digital go blurry, and action sequences have that incomprehensible shakycam look. The whole production feels faux cinematic, certainly too post-modern for an otherwise classical narrative.

Mann wants to tell a modern story, since Dillinger and Billie are timeless character archetypes, and reflect that with his camerawork. But leaving them in their chosen era suggests a classicism that Mann’s occasionally haphazard digital photography fails to capture. Perhaps he’s trying to imbue a sense of realism into this heavily romanticized world of gangsters and Tommy Guns, punctuated by his signature of deafeningly loud and exhilarating shootouts. After all, Dillinger is gunned down just after watching the Golden Age hit Manhattan Melodrama, a cinematic production of Dillinger’s gangster reality, suggesting that the Gable-Powell-Loy film is less real than Mann’s. So, if the director’s intent is realism as it compares to melodrama, perhaps the digital photography captures that feeling. Unfortunately, any sense of period realism goes further unsupported every time Otis Taylor’s modern electric banjo-rock tune “Ten Thousand Slaves” curiously plays on a soundtrack otherwise comprised of old-timey hits.

Mann wants to tell a modern story, since Dillinger and Billie are timeless character archetypes, and reflect that with his camerawork. But leaving them in their chosen era suggests a classicism that Mann’s occasionally haphazard digital photography fails to capture. Perhaps he’s trying to imbue a sense of realism into this heavily romanticized world of gangsters and Tommy Guns, punctuated by his signature of deafeningly loud and exhilarating shootouts. After all, Dillinger is gunned down just after watching the Golden Age hit Manhattan Melodrama, a cinematic production of Dillinger’s gangster reality, suggesting that the Gable-Powell-Loy film is less real than Mann’s. So, if the director’s intent is realism as it compares to melodrama, perhaps the digital photography captures that feeling. Unfortunately, any sense of period realism goes further unsupported every time Otis Taylor’s modern electric banjo-rock tune “Ten Thousand Slaves” curiously plays on a soundtrack otherwise comprised of old-timey hits.

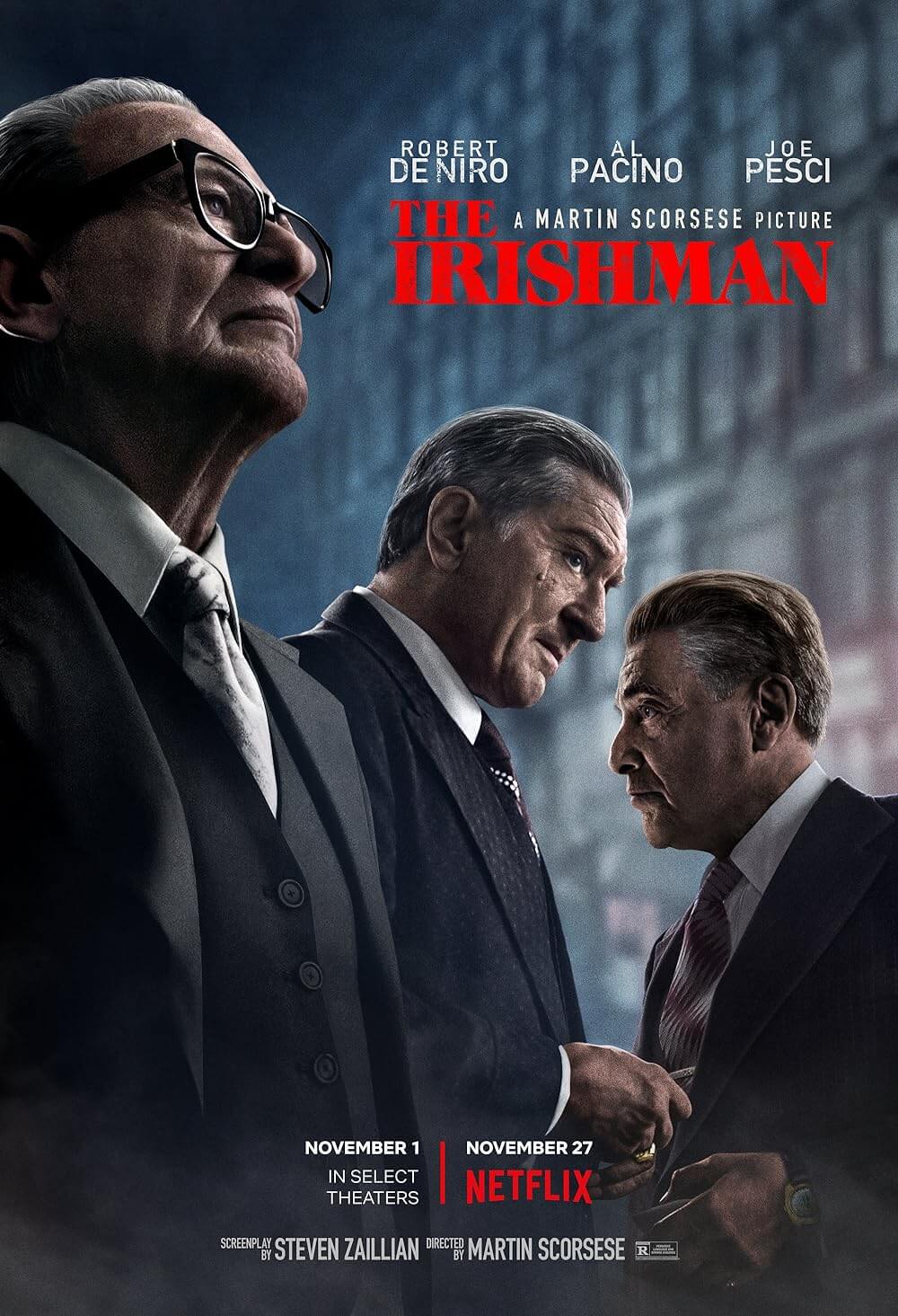

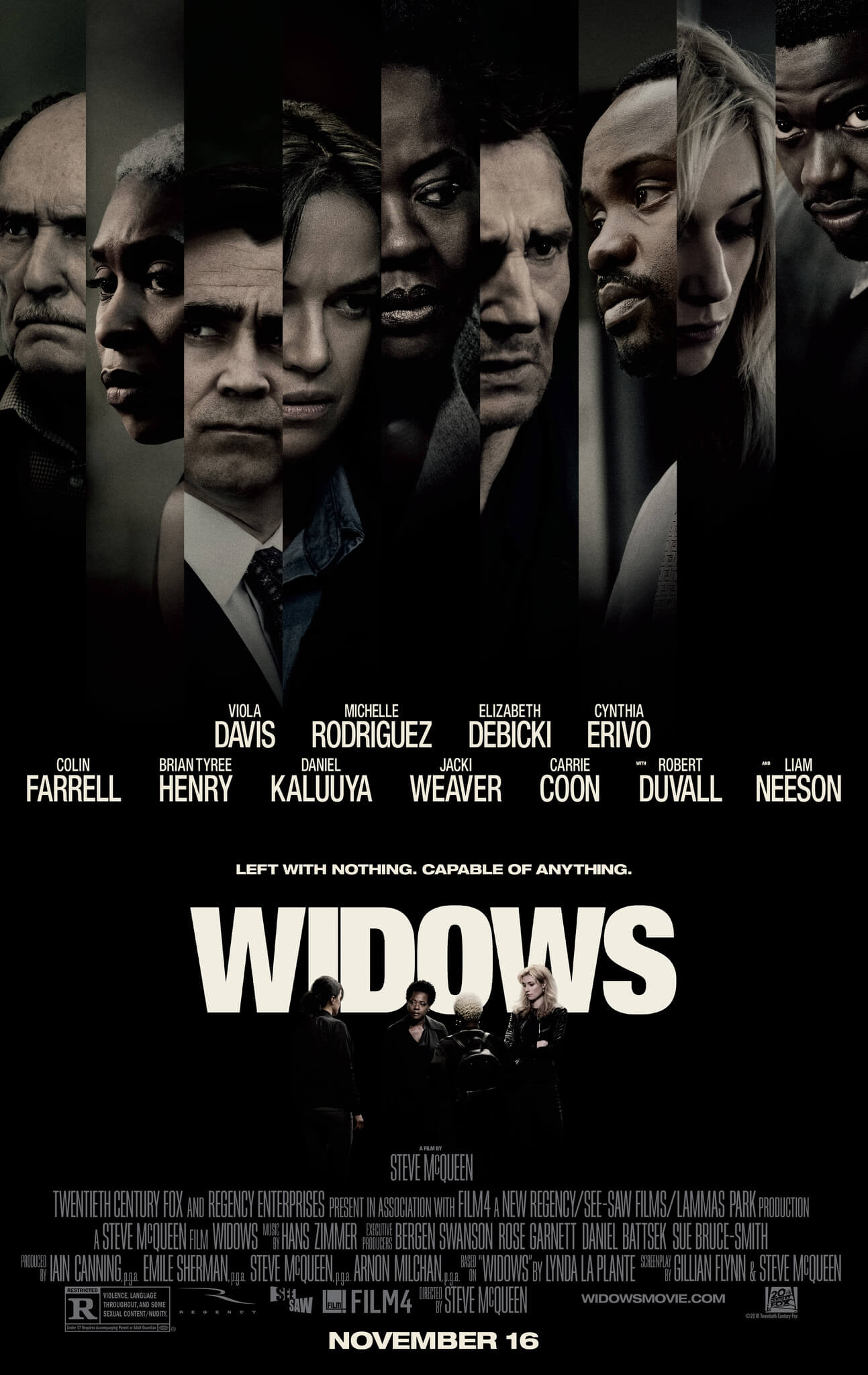

It’s a small tragedy that such stylistic flourishes prevent Public Enemies from being the great crime epic it should be, nearing on par with Mann’s own De Niro-Pacino coupling Heat. Like that film, cop and crook share barely any screen time here, save for a single poignant meeting in the second act. Depp and Bale give excellent performances both, particularly Depp’s somewhat understated rambunctiousness as Dillinger, a man the audience wholeheartedly empathizes with by the finale. Bale has less to do, however, because any motivation beyond merely catching the criminal is absent from the script by Mann, Ann Biderman, and Ronan Bennett. Just before the end credits, titles tell us Purvis committed suicide in 1960; perhaps Mann should have hinted at Purvis’ eventual outcome, delved into his background, or given the character some shades beyond your typical duty-bound G-Man. Had Bale’s character been fleshed out to match his costar, this film might’ve been a diptych instead of a portrait.

And so, Depp carries the film on his shoulders; his one-man band plays all those charming notes, and his devilish smile evokes how being bad can be so good. Though, it could be argued that he underplays the role—his Dillinger is certainly no Hunter S. Thompson or Jack Sparrow. Alongside him, Cotillard proves her Best Actress Oscar for La Vie en Rose wasn’t a fluke, that her acting chops extend beyond a single excellent performance. Her presence humanizes Depp’s Dillinger, and together they have wonderful onscreen chemistry. Until their characters meet and their relationship begins to flourish, Dillinger remains a wild child running free without purpose, leaving us detached. Only when they come together, about a third of the way in, does the film pick up, set clear stakes, and start to engage us.

Though Public Enemies spins a moving gangster yarn, the picture never transports us into the period. Sleek costumes, vintage cars, and original or reconstructed architecture add to the authenticity of Mann’s mise-en-scène; however, his technical choices, specifically the digital camerawork, distance us from the era. The approach eases how we relate to the characters because the effect is visually modern, but these choices leave cinematic and historic traditionalists craving a more polished, romantic look. Regardless, the merits of the production are sound, the performances interesting, and the broad strokes of the storyline involving. What remains impressive is that there’s no need to fictionalize actual events much beyond what Burrough chronicled in his history—they’re all thrilling enough on their own to keep us engaged.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review