Promising Young Woman

By Brian Eggert |

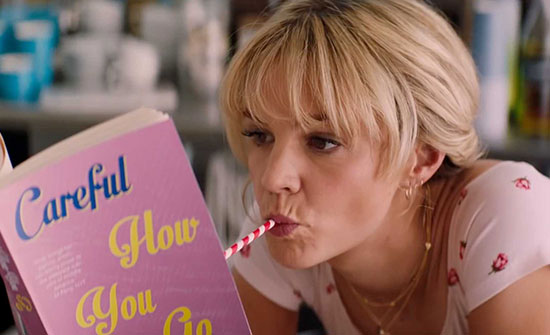

An early scene in Promising Young Woman finds Cassie, played by Carey Mulligan, faking drunkenness inside a yuppie businessman’s apartment. Thinking she’s barely coherent, he has lured her back to his bedroom, where she mumbles, “What are you doing?” He reassures her, “You’re safe”—even as he slips off her underwear. Then her sober voice asks the same question, “What are you doing?” as if to say, “Gotcha.” Every week, Cassie does some variation of this routine. She feigns intoxication at a nightspot, waits for some so-called nice guy, who doesn’t even know her name, to offer her a ride home. And when he inevitably tries to rape her, she turns the tables on him. She keeps the name of each perpetrator in her notebook, and there several pages of names. It’s a scheme designed to avenge her late best friend, the unseen Nina, who dropped out of medical school after a student raped her as others watched and laughed. Cassie, angry and grieving for her friend, has spent years confirming her worst beliefs about men while teaching them lessons in predatory behavior.

The film, written and directed by Emerald Fennell, offers a germane look at #MeToo movement issues through a wild array of tonal shifts, reflecting how such trauma creates a broken, unpredictable person. But ultimately, its resonant heroine feels undercut by the film’s playfulness, leaving its indictment of sexual violence against women and those who allow it to continue to take precedence over the emotional weight of the narrative. (Because the story’s tonal leaps prove so essential to the experience, it will be discussed in detail. Consider yourself warned.) It opens with a comically grotesque dance floor montage of yuppie businessmen in khakis and pale blue button-down shirts, gyrating their soft bodies in thrusts and pantomimed booty slaps. Later, an attorney played by Alfred Molina falls to his knees in a sobering scene, confessing that he will never forgive himself for defending Nina’s rapist and numerous others. At any moment, you might laugh at Cassie’s creative revenge scheme or feel shaken by the emotional toll. But rarely does it feel as if a version of Cassie exists outside the shadow of her friend’s experience.

Throughout the middle of the film, we follow Cassie, who dropped out of medical school with Nina and now works in a coffee shop, as she exacts revenge from a Kill Bill-like list in her notebook—each announced onscreen with pink Roman numeral titles. Besides her long register of night club predators, she targets enablers such as the classmate (Allison Brie) who refused to speak up about Nina’s rape or the college dean (Connie Britton) who still normalizes college rape culture. The method of Cassie’s revenge against these individuals is criminal, but no less point-making. At the same time, Cassie finds herself drawn to Ryan (Bo Burnham), a pediatrician and former classmate who seems down-to-earth. It takes a while for Cassie to let her guard down with Ryan, and once she does—cue falling in love montage—we see a glimpse of what she might be like if she was allowed to heal. But when Ryan reveals that Nina’s rapist is back in town after a long stint abroad, she’s forced to decide whether her life will be defined by her planned revenge or new happiness alongside Ryan. Alas, he makes the choice easy for her.

Throughout the film, I kept wondering about Nina. We get some impression of what she was like in life during anecdotes told by her mother (Molly Shannon), and in the climactic scene when Cassie confronts Nina’s rapist, but not much else. We learn she was fiercely independent and “fully formed from day one,” but no details about her treatment after her rape. The incident consumed her, just as it has consumed Cassie. Promising Young Woman suggests there’s no chance to heal after an experience like that; the only appropriate response is vengeance. Fennell leaps into the familiar rape-revenge movie logic that adopts an eye-for-an-eye morality. And just when you think the story might take the viewer in a more nuanced direction by emphasizing that revenge might be self-destructive—and that our society has designed itself to protect privileged white men from having to atone for their crimes—Cassie comes back with a last-minute jab that undercuts a more sophisticated message.

Throughout the film, I kept wondering about Nina. We get some impression of what she was like in life during anecdotes told by her mother (Molly Shannon), and in the climactic scene when Cassie confronts Nina’s rapist, but not much else. We learn she was fiercely independent and “fully formed from day one,” but no details about her treatment after her rape. The incident consumed her, just as it has consumed Cassie. Promising Young Woman suggests there’s no chance to heal after an experience like that; the only appropriate response is vengeance. Fennell leaps into the familiar rape-revenge movie logic that adopts an eye-for-an-eye morality. And just when you think the story might take the viewer in a more nuanced direction by emphasizing that revenge might be self-destructive—and that our society has designed itself to protect privileged white men from having to atone for their crimes—Cassie comes back with a last-minute jab that undercuts a more sophisticated message.

Catharsis certainly has its place in the movies. In Sophia Takal’s underrated remake of Black Christmas from 2019, the heroine, played by Imogen Poots, relies on sisterhood to get her through the trauma of rape. Eventually, her friends band together to fight back against the supernaturally inclined masculine cult. That film worked with its balance of social commentary and horror movie tone, whereas Promising Young Woman has the emotional weight of something more elevated, until it doesn’t. Cassie attempts to exact revenge on Nina’s rapist in the final scenes, but in a turn worthy of Michael Haneke, he gets the upper hand and kills her. It’s a shocking and deflating moment that reminds the audience about how movies often treat women victims (think Very Bad Things, 1998) and how men often get away with their actions. Had the movie ended there, I would have felt floored by its boldness. Instead, a final coda reveals how Cassie’s revenge plot isn’t over yet, and the men responsible finally receive their comeuppance.

While a commanding presence here, Mulligan appears in a fugue state, stricken by her trauma and the constant push and pull between grief, anger, and her suppressed desire for healing. She tells Nina’s mom that she’s “just trying to fix it,” but as Promising Young Woman progresses, it becomes apparent that there’s no way to repair this kind of damage. There’s only a capacity to live with what happened and find some measure of peace. By way of Fennell, Mulligan captures the fractured personality on display and how the easiest way for Cassie to define herself in the wake of Nina’s loss is revenge, no matter how much it consumes her. I only wish the film treated that choice as tragic rather than vindicating in the last seconds. Similarly, Fennell’s choice of loud pop songs on the soundtrack, from Paris Hilton to Charli XCX’s “Boys,” underscores the emotional complexity at work throughout the film—albeit with layers of irony that feel somewhat too winking for my taste.

While the final moments have a sense of belated relief, they diminish the shock of Cassie’s death. Catharsis feels too easy for a character as complicated as Cassie and too simple for a film as richly made as this. Fennell seems to argue that as women search for justice in a patriarchal world, they may not find it, not unless they keep at dismantling it. That’s easier said than done. No matter how many times Cassie logs another name in her notebook, there’s always another “nice guy,” another enabler, another denier who perpetuates the system. Even as Promising Young Woman acknowledges this, it delivers an ending that feels prankish instead of disquieting. But with its tonal imbalance and provocative choices, it’s an experience designed to incite debate among viewers, supplying a vital prompt and discussion about rape and the culture that perpetuates it. Even if I’m uncertain about whether I liked where the story goes, I remain moved and appreciative of Fennell’s willingness to try something unquestionably ambitious and admirably provocative.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review