Prometheus

By Brian Eggert |

In 1979, director Ridley Scott released his visionary film Alien and introduced audiences to an iconic movie monster and an unparalleled blend of science-fiction and horror. A number of sequels followed, but none of them, aside from James Cameron’s 1986 continuation Aliens, even came close to the sense of tension and visual majesty in Scott’s original. 20th Century Fox’s assorted line of troubled follow-ups and lazy spinoffs almost overshadowed the spectacular foundation boasted by this franchise. Several decades later, in an attempt to return the series to its original splendor, Scott has now made the pseudo-prequel (but more accurately labeled tangential spinoff) Prometheus, and with it demonstrates why his reputation as a master visualist has remained entrenched since he began making films more than thirty-five years ago. This work of epic-sized science-fiction contains moments of such incredible visual marvel that one cannot help but feel disappointed because its busy script, written by Jon Spaihts and Lost co-creator Damon Lindelof, has existential ambitions but none of the same grandeur as the formal presentation.

The film’s basic theme is a question humankind has asked throughout recorded history: Where do we come from? The writers attempt a cerebral exploration of this question, but they overreach by also trying to juggle too many characters and attain maximum accessibility within its commercial genre. The result feels unfocused and prone to multiple detours, which stray away from the central narrative highway into bumpy dirt roads and ultimately digress until they reach dead ends. Similarly themed large-scale productions, such as 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Tree of Life, conduct their existential investigations in a style where the audience is left questioning in ways that inform our curiosity. Both of those films are also profound works of art. First and foremost, Prometheus is a piece of Hollywood cinema meant to entertain us with neat sci-fi ideas and scary monsters, and there’s nothing wrong with that. But its admirable ambitions are undone by its conflicted filmic identity. The writers sidetrack the existential exploration to provide the audience with cheap thrills by way of dull humans being slaughtered by ugly things. In the end, we’re left with more questions than when we began. (Note: Many of these leftover questions and key plot elements will be discussed in detail within this review. Consider yourself forewarned.)

The film takes a moment from the 1979 original, when the crew of Sigourney Weaver’s ship, the Nostromo, locates an alien craft manned by an alien “Space Jockey,” and ponders who these intergalactic pilots are. Scott has said he didn’t want Prometheus to be a direct prequel to Alien; rather, it would just “share DNA” with the previous films. Fair enough. Appropriately then, the film opens with a scene involving the introduction of DNA into what is presumably a primordial Earth setting. The scenario of Prometheus would make Erich von Däniken proud, as it proposes an alien race created humanity. The first scene shows a humanoid alien set down by a flying saucer to spread genetic building blocks into the environment and inevitably create life. Cut to 2093, when the film’s human characters, following a star map left on prehistoric writings in ancient caves, set out into space on the titular craft to meet their makers. On the ship, the humans sleep in cryogenic chambers while David (Michael Fassbender), an android with more than a few similarities to HAL-9000, monitors the ship and creates a justified sense of unease and suspicion toward his character. He, too, wants to understand creation and has a maniacal curiosity to produce life.

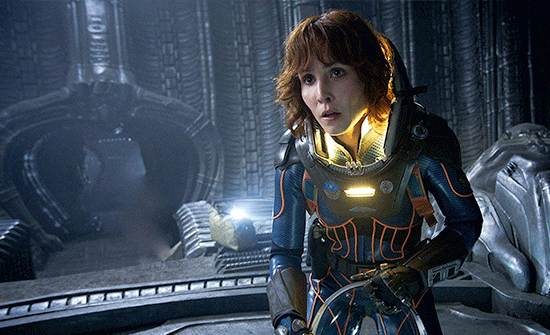

The mission has been funded by the Alien franchise’s malevolent corporate entity: Weyland Industries founder Peter Weyland (Guy Pearce), an elderly trillionaire who takes an interest when archeologist Elizabeth Shaw (Noomi Rapace) and her boyfriend Charlie Holloway (Logan Marshall-Green) locate what they believe to be an invitation from humanity’s “Engineers.” Overseeing the mission is Meredith Vickers (Charlize Theron), an icy figure obsessed with self-preservation, but her authority is often challenged by the ship’s captain, blue-collar everyman Janek (Idris Elba). Also along for the ride are a dozen or so scientists and medical officers who supply a body count once the film’s horrors unfold. But before any of that happens, the crew awakes from their cryo-sleep, and the ship sets down at their destination, where they quickly locate a structure built by the Engineers. They explore inside and find an abandoned series of tunnels and passages containing very old but advanced technologies. They find dead Engineer bodies piled up next to a door, having run away from something. What they were running from, we never learn. But once the humans enter this environment, it begins to react to their presence. Metallic vase-like cases ooze deadly black organic matter, and the gloppy stuff produces wormlike things that enter the body and cause disease or, in one case, mutate a victim into an extremely violent attacker. There’s not much rhyme or reason to the ooze and how it affects its victims; it’s a far cry from the clear life cycle and biological workings of Alien’s xenomorph. But don’t get any on you, and certainly don’t swallow any.

The mission has been funded by the Alien franchise’s malevolent corporate entity: Weyland Industries founder Peter Weyland (Guy Pearce), an elderly trillionaire who takes an interest when archeologist Elizabeth Shaw (Noomi Rapace) and her boyfriend Charlie Holloway (Logan Marshall-Green) locate what they believe to be an invitation from humanity’s “Engineers.” Overseeing the mission is Meredith Vickers (Charlize Theron), an icy figure obsessed with self-preservation, but her authority is often challenged by the ship’s captain, blue-collar everyman Janek (Idris Elba). Also along for the ride are a dozen or so scientists and medical officers who supply a body count once the film’s horrors unfold. But before any of that happens, the crew awakes from their cryo-sleep, and the ship sets down at their destination, where they quickly locate a structure built by the Engineers. They explore inside and find an abandoned series of tunnels and passages containing very old but advanced technologies. They find dead Engineer bodies piled up next to a door, having run away from something. What they were running from, we never learn. But once the humans enter this environment, it begins to react to their presence. Metallic vase-like cases ooze deadly black organic matter, and the gloppy stuff produces wormlike things that enter the body and cause disease or, in one case, mutate a victim into an extremely violent attacker. There’s not much rhyme or reason to the ooze and how it affects its victims; it’s a far cry from the clear life cycle and biological workings of Alien’s xenomorph. But don’t get any on you, and certainly don’t swallow any.

As the crew attempts to understand their discovery and what it means, we try to figure out the crew, whose motivations meander about and provide many inconsistencies. The film’s heroine, the blindly hopeful Shaw, somehow remains a stringent Christian despite what she’s found out about our origins and clings to a cross around her neck because it reminds her of her late father (Patrick Wilson, in a cameo), who appears in a needless dream sequence. More disenchanted, Charlie wants to ask the Engineers why they created human life and why they abandoned us, but he feels even more abandoned when the Engineers aren’t there to greet him. Vickers has no interest in humanity’s origins; she wants only to return home safe and sound. David’s motivations are more perplexing. He has secret personal ambitions to experiment with the black ooze and return to Earth with it for study—perhaps to destroy humanity?—but his service to Weyland, who has secretly come along for the ride in search of immortality, never allows us to find out what David is up to. When these characters learn the Engineers’ lair is, in fact, a flying arsenal designed to destroy the human race, the questions about the order of the universe only intensify. Meanwhile, none of these characters realize a fulfilling dramatic arc, while some (like Charlie and Vickers) are disposed of in silly ways, and so our involvement in their philosophizing leads nowhere.

Worse, most of the peripheral “body count” characters suffer from underdevelopment, while in some cases, the main characters are inelegantly overwritten. For the supporting cast, Spaihts and Lindelof embed a surprising and off-putting amount of pop-culture references, superfluous banter, and comic relief for a film with lofty existential aspirations. Elsewhere, the writers inject moments of forced character development to add needless emphasis. These are characters who ask questions about their origins by literally asking them aloud. Indeed, the writing is not what someone might call subtle. Consider a scene inside Elizabeth and Charlie’s quarters after their initial excursion to the Engineer’s ship; they debate about the significance of their discovery, and then suddenly, Charlie says the wrong thing about the power of creation. Elizabeth begins to cry because, as she reminds him (and thus informs the audience), she cannot have children. This scene unfolds ineptly, as its sole purpose is to foreshadow her imminent and ironic pregnancy with an alien organism, which leads to the film’s nastiest horror sequence when she commits a self-guided Caesarian section. Another scene has Vickers all but bowing to Weyland as she kisses his hand, and then the scene twists when she melodramatically calls him “father” with such an awkward pause afterward that we expect a commercial break to follow. Next week on Days of Our Lives…

Of course, Scott’s craftsmanship behind the camera supplies no end of visual wonders to counteract the humdrum story. To be sure, the director has never been accused of delivering a picture with deficient technical elements. Shooting in Iceland during the recent volcanic activity, he captures the primordial atmosphere for the prologue sequence. Later, his aerial camerawork glides over beautiful landscapes that appear untouched by civilization. The future technologies, such as the Prometheus spaceship, are flawless looking. There hasn’t been a science-fiction film of this scope in theaters for some time. The CGI used to render the Engineers and the flight of their spaceship looks downright amazing, but the design of the various slimy creatures and Engineers themselves lacks the iconographic edge H.R. Giger brought to the original designs. If there’s anything keeping the audience involved, it’s Scott’s immersive grandiosity and its support by a fine cast of actors. Rapace, Fassbender, Elba, and Theron each lend their characters more presence than the script affords, with Fassbender as the standout in a devious and carefully nuanced performance.

Of course, Scott’s craftsmanship behind the camera supplies no end of visual wonders to counteract the humdrum story. To be sure, the director has never been accused of delivering a picture with deficient technical elements. Shooting in Iceland during the recent volcanic activity, he captures the primordial atmosphere for the prologue sequence. Later, his aerial camerawork glides over beautiful landscapes that appear untouched by civilization. The future technologies, such as the Prometheus spaceship, are flawless looking. There hasn’t been a science-fiction film of this scope in theaters for some time. The CGI used to render the Engineers and the flight of their spaceship looks downright amazing, but the design of the various slimy creatures and Engineers themselves lacks the iconographic edge H.R. Giger brought to the original designs. If there’s anything keeping the audience involved, it’s Scott’s immersive grandiosity and its support by a fine cast of actors. Rapace, Fassbender, Elba, and Theron each lend their characters more presence than the script affords, with Fassbender as the standout in a devious and carefully nuanced performance.

It’s necessary to view Prometheus as a totally separate entity from the Alien franchise; it doesn’t make sense otherwise. When the film ends, there’s no obvious lead-in to Alien, but the ending does hint at a sequel featuring Shaw, the sole survivor who escapes on an Engineer spaceship determined to find the Engineer homeworld, where, I suppose, she plans to confront them for answers. Although she’s on an alien ship, she somehow records a final log entry mirroring the one Ripley makes at the end of Alien; there are other likenesses to the original film, all faint and unnecessary if Scott’s intention was not to connect this film to the earlier one. After Shaw blasts off, we see how one of the Engineers has become victim to an octopi-esque black ooze creature—a xenomorph-shaped monster, but not like one we know, bursts from the Engineer’s chest and evokes a strong sense of HUH?! and incites unintentional laughter. It had none of the mystery or fear of Giger’s original alien design. It should also be noted that the moon setting of Prometheus is called LV-223, whereas the planetoid in the Alien films was LV-426. This illustrates how disconnected Prometheus is from the previous films, and it should supply devotees to those films ample ammunition with which to apologize for this one’s disparities. However, no matter how far Scott attempts to distance this work from the other films, its script still lacks interesting characters or any kind of dramatic closure.

For fans of the Alien series, this highly publicized, highly anticipated film will feel like an incredible letdown. It doesn’t work as a prequel, but then it doesn’t necessarily need or want to. As a result, you might conclude that Prometheus would work best for fans of the sci-fi/horror subgenre not yet familiar with the previous Alien films. Though it’s unbelievable any such a person could exist, this hypothetical moviegoer would nonetheless find themselves taken aback by the film’s open-ended conclusion and its inability to satisfy on any emotional level. The flaws in the screenplay undo even Ridley Scott’s profound level of visual brilliance, which is on considerable display here. This is unfortunate, as there are great ambitions and great filmmaking at the root of Prometheus. But more prominent is the cluttered writing from Spaihts (whose sole credit is 2011’s post-apocalyptic dud The Darkest Hour) and a conclusion whose severe level of discontent should feel familiar to those who remember Lindelof’s convoluted ending to Lost.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review