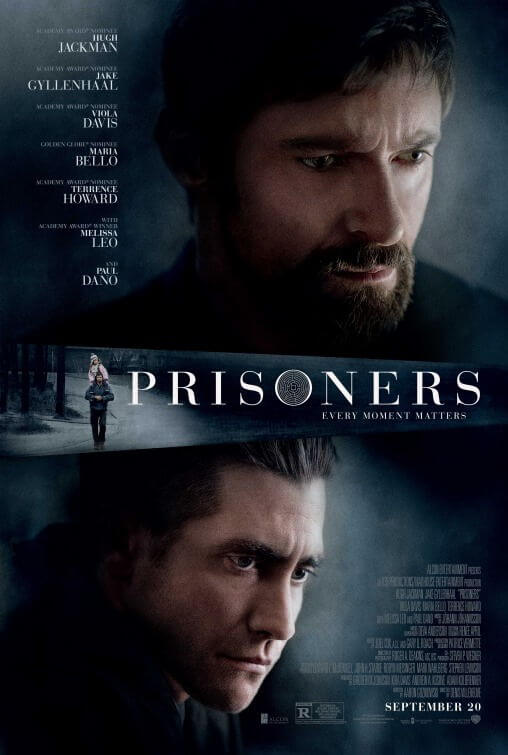

Prisoners

By Brian Eggert |

A gravely told drama for adults revolving around the abductions of two children, Prisoners centers on the families and investigating detective related to the crime through measured, confident direction by Quebecois director Denis Villeneuve. Impelled by staggeringly good performances from its ensemble cast, the film rises above its genre picture roots to become not only an effective mystery and intense thriller, but also an intricate consideration of vengeance, faith, justice, and loss. Inside a two-and-a-half-hour runtime, Villeneuve and his prestige-level players develop and deepen Aaron Guzikowski’s screenplay, its complex characters and situations held captive by an ever-present sense of dread. And while talk of the film’s Oscar-worthiness may perhaps be overstated, the film belongs on the same list as similar award-worthy dramas as Clint Eastwood’s Mystic River and The Changeling or David Fincher’s Se7en and Zodiac.

As their families engage in post-Thanksgiving meal conversion and sleepy television viewing, two young girls from neighboring suburban Pennsylvania families disappear. The Dovers, headed by paterfamilias Keller (Hugh Jackman) and dependent mother Grace (Maria Bello), search for the girls frantically alongside their friends, the Birches, father Franklin (Terrence Howard) and mother Nancy (Viola Davis). The missing girls, Anna (Erin Gerasimovich) and Joy (Kyla Drew Simmons), have vanished on a walk, and their older siblings, Ralph (Dylan Minnette) and Eliza (Zoe Borde), remember them playing near a creepy RV earlier in the day. On this case, Det. Loki (Jake Gyllenhaal) quickly tracks down the suspect, whom he’s soon forced to release as no physical evidence is found in his RV. A child in the body of a man, the eerie suspect Alex (Paul Dano) is mentally impaired and can’t, or won’t, answer Loki’s questions. Convinced Alex is guilty, Keller resolves to kidnap the now-free believed kidnapper and violently interrogate him to determine the girls’ location.

Challenging in its treatment of vigilantism, the film’s characters never become simple creatures driven to extremes of cathartic violence. Keller—a god-fearing, all-American hunter, carpenter, and survivalist, whose motto “be prepared” is expounded by his basement stocked with emergency provisions—would seem to be purely fanatical, except his piety forces him to question his resolve more than once. Franklin goes along with Keller’s plan at first, until his conscience begins to weigh on him; but Nancy would rather let Keller do what he must, just in case his suspicions are correct. Grace cannot cope at all and loses herself in prescription narcotics to numb the pain. Even Loki, who has never left a case unsolved, is more than your usual determined cop; his tattoos and heavy blinking show signs of a detective haunted by stress and the feeling that something is wrong with this case. Each of the performances on display here is just as multifaceted as their characters, with particular emphasis on Jackman and Gyllenhaal, who deliver the film’s most impressive turns (Gyllenhaal mined similar territory in Zodiac, though the characters are very much different). Melissa Leo also appears as Alex’s aunt, a quiet loner who’s convinced her nephew is innocent.

The film’s vigilante subplot soon gives way to a tragic narrative, and Guzikowski’s script veers in unexpected directions, later proving to be an elaborate, tightly knit canvas where no detail is meaningless. If a fault must be found in Prisoners, it’s that Villeneuve allows the keen viewer to notice certain details and realize their connections to the mystery before some of the onscreen characters do. This happens more than once in the film, most notably in the last scene, and such a quality may weaken the film’s overall suspense for some. However, the film is less a whodunit than a densely packed drama about how people cope, or refuse to cope, with a tragic situation. Villeneuve’s formal treatment is fitting as a result, enhanced by Roger Deakins’ gorgeous cinematography of earthy, autumnal colors, overcast skies, rain, and snow. The visual solemnity is in perfect balance with the film’s bleak atmosphere and somberness. Editors Joel Cox and Gary Roach, Eastwood’s longtime collaborators, never cut too fast, and in fact, hold onto a number of Deakins’ shots until the audience is forced to look further into the scene.

Being Villeneuve’s first Hollywood picture, Prisoners shows all the attention to character and mood as one of his independent foreign-language projects, yet with the scale and sheer star power you might expect from a larger Warner Bros. production. But this kind of dark material is rarely seen in Hollywood anymore—except directors such as the aforementioned Eastwood and Fincher—whereas Villeneuve is no stranger to grim subject matter. His Oscar-nominated Incendies (2010) involved incestuous rape and religious identity, so a kidnapping may seem like a walk in the park by comparison. Still, this is no easy experience and may leave the viewer disturbed, but nevertheless, with something of dramatic substance to talk about afterward. The weight imbued into the characters is engrossing, and the story itself leaves us equally intrigued and shocked, every emotion along the way flawlessly realized by the wonderful cast. At times a predictable mystery and a familiar plot, Prisoners remains an absorbing, skillfully made drama.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review