Prince Avalanche

By Brian Eggert |

Prince Avalanche might just be the perfect metaphor for writer-director David Gordon Green’s career thus far. Since his debut in 2000 with his rural realist piece George Washington, Green has helmed some of American independent cinema’s finest samples. There’s the gentle romance All the Real Girls from 2003, his foray into Southern Gothic with 2004’s Undertow, and the wintry tale of tragedy in Snow Angels (2007). In recent years, Green has “gone Hollywood” with a number of increasingly stupid comedies starring his friend Danny McBride, beginning with HBO’s Eastbound & Down, then segueing into the hilarious Pineapple Express (2008), and his two unfortunate releases from 2011, Your Highness and The Sitter.

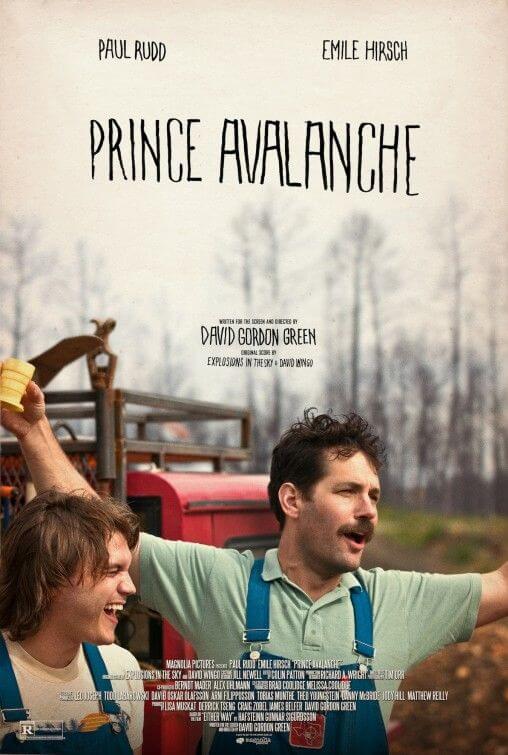

Based on the 2011’s Icelandic film Either Way by Hafsteinn Gunnar Sigurðsson, Prince Avalanche combines the peaceful, restrained approach of Green’s earlier indie dramas and populates it with the kind of aimless heroes that fill his commercial comedies. In limited release by indie label Magnolia Pictures, the film takes place in Texas in 1988, not long after fires consumed 750,000 forest acres and destroyed a number of homes in the process. On a stretch of highway rolling through the recuperating woodlands, the two-man road crew of Alvin (Paul Rudd) and Lance (Emile Hirsch) paint yellow divider lines on the highway and hammer reflectors into the roadside. They’re completely isolated in their work in an era without cell phones or portable computers, just two men in the woods, scenery abound, and without much of anything to say to one another.

During the day, they paint miles of yellow dashes, and each night they make camp on the side of the road. Alvin, an uptight guy who enjoys Nature, seclusion, and self-improvement (he listens to German language lessons on tape), has been on the job since the spring. Only for the summer has Alvin secured the job for Lance as a favor, Lance being the brother of Alvin’s offscreen girlfriend. By contrast, Lance is an average clod who struggles to get through the week with no one but Alvin for company. Desperate for a woman, Lance takes to quietly masturbating in their tent as Alvin sleeps. Their sole break from one another comes in the form of a local trucker (Lance LeGault), who provides them with homemade moonshine and offers them strange life lessons, only to disappear again. One day after receiving a letter from his girlfriend, Alvin goes quiet. To find out why, Lance sneaks a peek at the letter and learns Alvin has been dumped by his sister.

What ensues is a surprisingly touching display of male bonding between two characters with whom Green is clearly fascinated, yet doesn’t need to explore beyond their simplicity. Rudd is pricelessly awkward in his eccentric body language, delivering his lines with sincerity behind a mustache and persnickety mannerisms. During a weekend when Lance is away, Alvin wanders onto a property ruined by the recent fires and finds an elderly victim (Joyce Payne) sifting through the ashen leftovers. Rudd is so achingly empathic with this broken woman, but in the next minute, he finds the skeleton of another burned house and mimes a coming-home-to-the-family routine in a wryly comic moment. Hirsch’s charm is less contained; he’s playing a nicer, redeemable version of his vile hillbilly from Killer Joe, but just as dimwitted. Costume designer Jill Newell has them both dressed in official Texas roadside overalls and varying degrees of silly Eighties clothing.

Filmed in the Bastrop State Park after the 2011 Bastrop County Complex fire, the most destructive wildfire in Texas history, Prince Avalanche looks beautiful. Green’s recurring cinematographer Tim Orr captures natural beauty in the area’s flora and fauna, while Green himself lingers on everything in the frame, from the tedious work performed by the two protagonists to the inching crawl of a caterpillar on a fallen log. The film—whose title has no particular meaning whatsoever, according to the director—ruminates on the steady, slow pace of its character’s emotional states and compares this visually to the gradual healing of the surrounding woodlands. The experience isn’t about following through with a plot; rather, it’s about immersing us in a state of recovery. It’s quietly enjoyable, sort of infectious even, and a welcomed return to independent cinema for this filmmaker.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review