Presence

By Brian Eggert |

Presence turns the ghost story inside out. Although most haunted house fare occupies the perspective of those who witness or become haunted by a specter, Steven Soderbergh’s film unfolds from the subjectivity of a ghost with unfinished business on this earthly plane. In a simple but sophisticated innovation on the haunted house genre, the director and his screenwriter, David Koepp, tell their story with the camera serving as the ghost’s point of view. Of course, it’s not without precedent to have a ghost as the main character, either as an open detail or late-movie reveal—see The Sixth Sense (1999), The Others (2001), and A Ghost Story (2017). But Soderbergh and Koepp conceived Presence with a harmony between its technical form and narrative function, resulting in an inspired and distinct approach: an entire film that uses the camera as a transparent character. Fortunately, besides its formal conceit, Presence is also a damn good thriller and mystery.

Having worked consistently since sex, lies, and videotape (1989)—apart from his short retirements—Soderbergh’s career has recently returned to a place of experimentation. In the years following his Palme d’Or-winning debut, he helmed several independent, sometimes avant-garde commercial failures, from Kafka (1991) to Schizopolis (1996), that explored the limits of film form. By the end of the 1990s, he resolved to play Hollywood’s game by his rules and became one of the most reliable filmmakers for turning out stylized and often socially conscious star-driven productions, such as Out of Sight (1998), Traffic (2000), the Ocean’s trilogy, and Contagion (2011). But since star power has dwindled in Hollywood in favor of IP, Soderbergh has returned to independent productions, such as shooting Unsane (2018) on an iPhone or making the Koepp-penned KIMI (2020) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Soderbergh and Koepp each tackle familiar territory in novel ways, and both are acutely aware of the supernatural horror genre’s usual trappings—the opening titles even have the same hollowed-out font as Poltergeist (1982), its outline cleverly suggesting an apparition. With Presence, Koepp’s screenplay offers a similar setup, complete with a family in a new suburban home inhabited by a spirit, and later, visited by a medium who senses the entity. But rather than a domestic blockbuster shocker akin to what director Tobe Hooper and producer-writer Steven Spielberg delivered, Soderbergh’s lower-key story balances its mischievous visual agenda with tense family dynamics and an unsettling reveal. Before ever getting to the story, however, Soderbergh’s first-person camera glides around the empty and unfurnished house, both establishing the spatial geography of the ensuing film and how the spirit remains trapped inside.

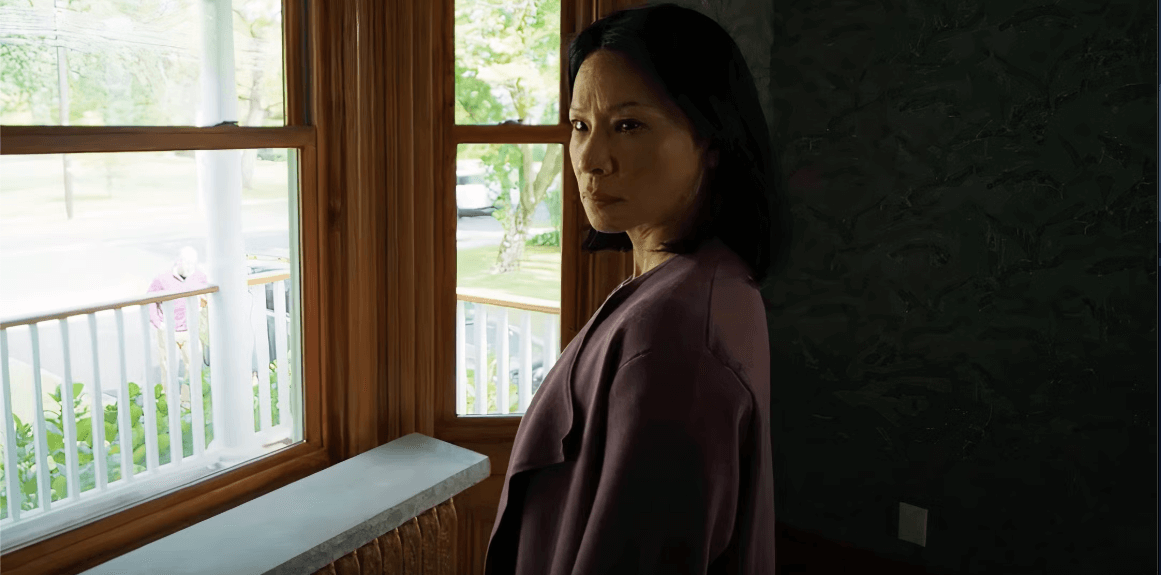

Along with its single location and modest $2 million budget, Presence boasts a limited cast of characters. There’s a brief appearance by a real estate agent named Cece (Julia Fox), who shows the house. Otherwise, the action centers on the family of four that moves in: the mother, Rebecca (Lucy Liu), has some shady business going on with a possible legal fallout ahead. Her husband, Chris (Chris Sullivan) knows something’s up, but communication isn’t their strong suit. Then again, Rebecca has no problem talking to their teen son, Tyler (Eddy Maday), her eldest and unabashedly favorite child. But Chris gravitates toward their daughter Chloe (Callina Liang), an inward teen who recently lost two friends to drug overdoses. Outside of the family, there’s also Ryan (West Mulholland), a popular kid at Tyler and Chloe’s high school, who hangs out with Tyler but has eyes for Chloe.

With Soderbergh operating the camera under his oft-used pseudonym Peter Andrews, every image is seen by the film’s metaphysical silent witness. The camera movements glide about the house in long, fluidly captured, searching sequences. Under his editing alter-ego, Mary Ann Bernard, Soderbergh breaks up the sequences by cutting to black, as though the entity has closed its eyes or faded out of time and space momentarily. This POV narrative technique recalls last year’s Nickel Boys, RaMell Ross’ adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s novel. But where Ross alternates between various characters’ perspectives, Soderbergh is far more committed and consistent. His ghost-camera follows characters, observes their conversations, and interacts at crucial moments. All the while, the viewer might pause to consider what’s going on behind the scenes—one imagines Soderbergh running around the house in socks, holding the camera gimbal and chasing after his actors. He even gives a performance with his camera, retreating into a closet or urgently trying to get a character’s attention.

All of this might register as a mere gimmick worthy of William Castle—the B-movie producer and huckster known for promotional devices such as Percepto (The Tingler, 1959), Emergo (House on Haunted Hill, 1959), and Illusion-O (13 Ghosts, 1960)—except Soderbergh and Koepp weave the visual device into the plot. No stranger to ghost stories, Koepp has written and directed similar supernatural-themed material with Ghost Town (2008) and You Should Have Left (2020). However, Presence most closely resembles his 1999 effort, Stir of Echoes, given their comparable revelations in the third act. Though known for scripting massive blockbusters such as Jurassic Park (1993), Mission: Impossible (1996), Spider-Man (2002), and the last two Indiana Jones adventures, Koepp has a penchant for claustrophobic stories in a single location, as evidenced by his scripts for Panic Room (2002) and Secret Window (2004).

The narrative and visual premise find an ideal form-follows-function pairing in the writer and director, which they support with a moving story and confronting themes. Every camera movement is a gesture, expressing an emotion or mood the way body language does. And while Presence is a worthy conceptual project, perhaps more importantly, it’s a good yarn. The plot drives our attention, piecing together a mystery with clues from a medium (Natalie Woolams-Torres) and a vintage silver-nitrate mirror, which lead to places best left for the viewer to discover. No matter how innovative Soderbergh’s camera may be, the story always comes first, establishing dimensional characters with efficient dialogue and complex family dynamics. The casting is especially effective, with newcomer Liang serving as a wounded conduit capable of sensing the ghost. Sullivan’s performance as the beleaguered father also shines.

Acquired by Neon at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival,- Presence is exceptional because it forces moviegoers to think about the camera and the narrative simultaneously. Most viewers rarely, if ever, consider what the camera is doing, much less what the camera thinks based on its movements. In most films, the camera is an apparatus that supplies the image—a conveyance or literal lens through which to view the story. By making the camera a character, Soderbergh and Koepp thoughtfully call their viewers’ attention to filmmaking in a way other movies seldom do. The effect is almost unconscious, since the formal strategy is guided by the story. But it’s a testament to Soderbergh’s continued willingness to stretch the limitations of commercial entertainment by rethinking formal solutions. That Presence is also chilling, resonant, and wholly immersive makes it that much more rewarding.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review