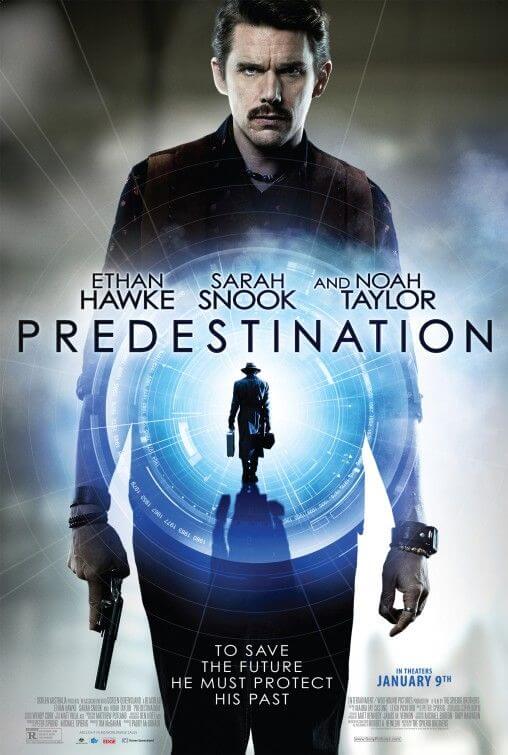

Predestination

By Brian Eggert |

A guy walks into a bar and tells the bartender that his life story is unlike anything the bartender has ever heard. Accustomed to people telling him their stories, the chatty bartender bets the guy a bottle of bourbon that his story isn’t anything he hasn’t heard before. And so, the guy proceeds to tell the story of his life, involving allusions to an ongoing identity crisis, a sex change, a stolen baby, and an aspiration for space travel. The bartender gives the guy the bottle of bourbon. And this is even before the guy’s story delves into time travel, temporal paradoxes, or the many other plot twists found in the smart sci-fi feature Predestination. What begins as a story relayed in flashbacks becomes a mind-boggling series of plot turns that maneuver the narrative into a puzzle. And while time travel films usually employ large-scale sci-fi action to distract from the holes, this film prefers the audience carefully consider the tightly wound events right along with the characters and what’s happening to them.

Written and directed by the Spierig brothers, Mike and Peter, the film closely follows their source, Robert Heinlein’s short story “All You Zombies.” Heinlein’s story was written in 1959, and looking back now, the technology and settings may seem dated; for example, he wrote that time travel was invented far in the future… in the 1980s. Quite refreshingly, the Spierigs follow Heinlein’s text in detail, setting their film in what amounts to an alternate timeline where the events after 1959 are nothing like what’s written in our history books with events that jump around to various points between 1945 and 1993. In Heinlein’s and therein the Spierigs’ version of the mid-to-late twentieth century, a terrorist who the media has dubbed the “Fizzle Bomber” destroys targets every few years without cause or discrimination, and investigators are left baffled. An agency called The Temporal Bureau sends an agent, played by Ethan Hawke, back to 1970 to stop the bomber, using a portable time machine he carries in a violin case.

But “man travels back in time to catch a terrorist” is just the trailer-ized plot synopsis. About half the film plays out in flashback, relayed to Hawke’s character, who has disguised himself as a bartender in 1970. As mentioned above, the male patron (Sarah Snook) tells his story on the aforementioned bet—how he came to write magazine confessional stories under the byline “an Unmarried Mother”. And yet, the patron’s story begins as a newborn baby named Jane is delivered to an orphanage. As she grows up, Jane notices that she’s different from her fellow orphans. She’s smarter, particularly in math and physics, and she’s tougher too, often finding herself the victor in schoolyard rumbles. When she reaches womanhood, Jane hopes to travel to the stars for a company called Space Corp., where she’s recruited by the secretive Mr. Robertson (Noah Taylor), but only as a diversion to the male astronauts. Robertson knows she has more potential, however. Meanwhile, Jane has fallen for a mysterious man (whose face never appears onscreen) who beds her, disappears, and leaves her with a baby.

Her story continues to grow stranger and more complex when, after giving birth, she learns that she was born with both male and female sexual organs, and the male organs were virtually hidden inside her. As she goes through a forced series of operations for sexual reassignment, her story reconnects with Mr. Robertson and his newly formed agency based in time travel. A sense of Ouroboros sets in, with Jane’s story looping back and somehow interconnecting with that of Hawke’s character. The viewer spends much of the film simply trying to understand how these connections are made and what could possibly come next. How do Snook and Hawke’s characters relate to one another? What, if anything, do they have to do with the “Fizzle Bomber”? Ultimately, the journey there is much more satisfying than the destination, and the viewer should almost watch the movie from start to finish twice, back to back, to fully appreciate and identify the filmmakers’ clues within the plot.

(NOTE: A major plot twist exists near the end of Predestination that may lose some viewers. Skip to the last paragraph if you chose to remain unspoiled. This paragraph will discuss it in detail.) If there’s a significant problem with the film, it’s the treatment of the twist at the very end, where it’s revealed that Hawke and Snook’s characters are actually the same person. At some point after the sex change, the male Jane went back in time and became the faceless lover of her younger, female self. What’s more, excessive time travelling has caused Hawke’s version of the character to go mad and in due course become the Fizzle Bomber. Only after a horrible fire and facial reconstruction surgery does Snook’s version become Hawke’s version. However, the two actors look nothing alike, and the greatest leap we’re expected to take in following this temporal causality paradox is that Snook could somehow transform into Hawke, whereas believing that Snook’s attractive female self and androgynous-looking male self are the same is no stretch at all. This visual inconsistency is enough to take a viewer out of the experience.

That visual hangup aside, Predestination has been carefully executed and constructed by the Spierigs, and it makes great use of the song “I’m My Own Grandpa” too. The film moves at a deliberate pace, carried along by Peter Spierig’s downtrodden score and the consistent, detailed sets by production designer Matthew Putland, and sharp widescreen lensing by Ben Nott, which subtly differentiates each of the various periods. Far removed from their cultish first film, Undead from 2003, and their slick and somewhat elevated second effort, Daybreakers from 2010, their latest shows a maturation of talent and content. Because the material is so complex, it would have benefitted from more screentime devoted to the characters themselves. Essentially, Predestination is a plot-oriented exploration into a causality loop that leaves the viewer with a problem to work out in their heads. Allowing more time with these characters and their emotional consequence could have resulted in something superior, more akin to Looper. And while the resulting film may prove somewhat cold and not completely satisfying on a dramatic level, it’s a fascinating investigation into the major science-fiction theme of time travel and the sometimes mindbending possibilities therein.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review