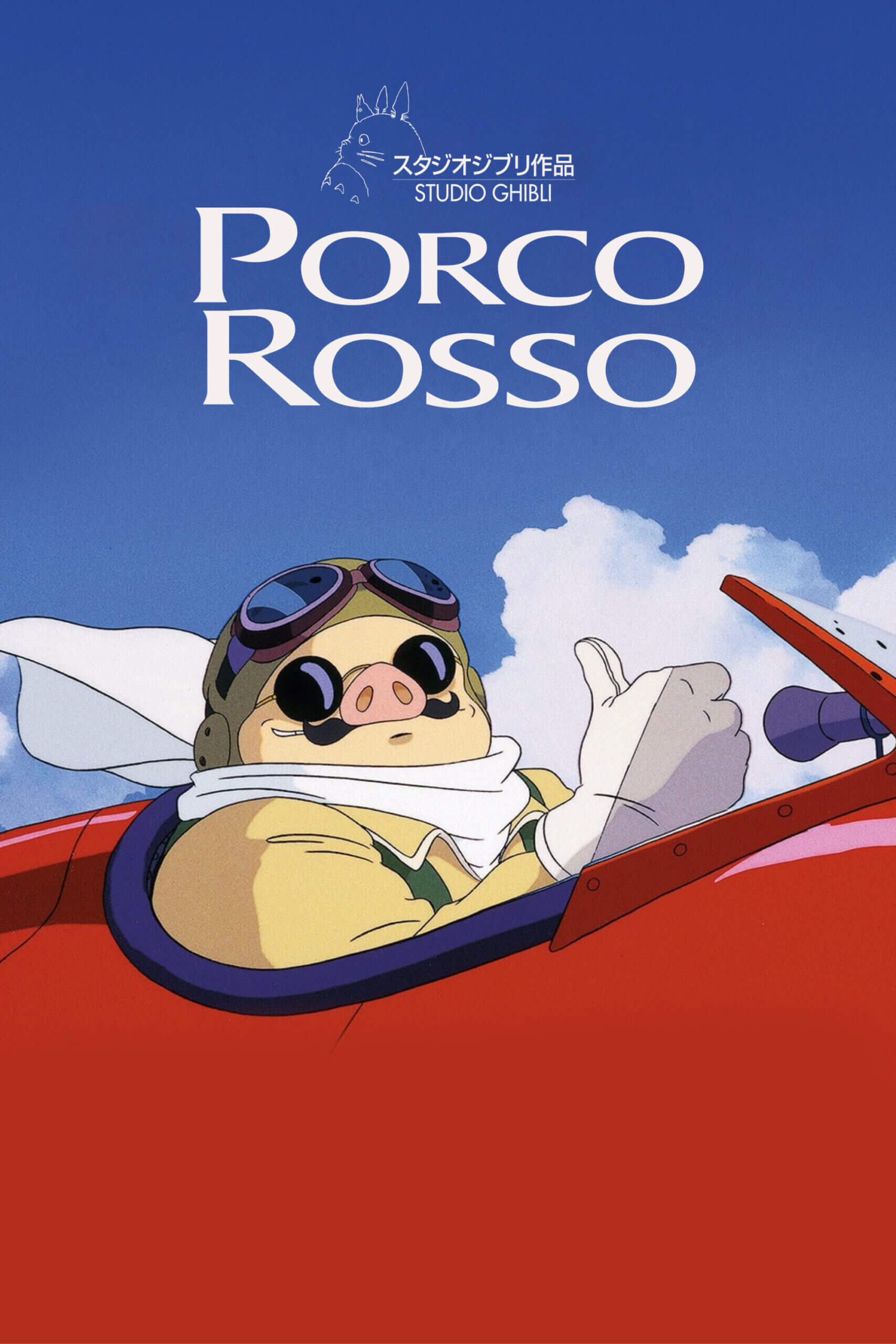

Porco Rosso

By Brian Eggert |

A celebration of his own fascination with aviation, director Hayao Miyazaki’s Porco Rosso stands out among the Japanese animator’s films. Where normally his settings remain somewhat ambiguously placed in time, here the story takes place in a definite period of history, adhering to the rules of those surroundings completely. Of course, Miyazaki’s sense of fantasy still emerges, but only as a device to further describe his intriguing protagonist, a pilot-cum-pig. The surrounding details of the scenario provide a high-flying adventure with conflicts to resolve but no sense of perilous danger. It’s colorful, innocent, bright, and most importantly romantic in the most expansive capacity of the word.

What a strange and exciting adventure this is; though it was originally meant for blind escapism, it has ironically become more elegant for its straightforward approach. Miyazaki wrote in his brainstorming notes that he envisioned the project to be so effortless that businessmen exhausted from international flights could enjoy it “even if their minds have been dulled from lack of oxygen.” Japan Airlines floated the bill for his proposed 45-minute minute in-flight film, which consisted mostly of airplane dogfights, romance, and humor akin to more popularized realms of Japanese anime. The final product, however, evolved into something much more substantial.

Indulging himself through varying flourishes of genre and seaplane fanaticism, Miyazaki constructs period realism and B-movie finesse in the vein of 1930s serials—high adventure and low brows, except Miyazaki manages to raise those limitations. Miyazaki doubled the runtime to insert a weighty interlude ripe with his usual feminist social commentary as a break from the film’s action. His expanded treatment, still backed by the airline, ended up a full-length feature when the script was completed, though his film was no longer for an exclusively adult audience. Porco Rosso may challenge some children with its period details and instill heavier themes into the subtext than one might expect, but Miyazaki treats his audience with respect no matter the age—a trademark of the director’s approach to storytelling, and something he could not circumvent even when trying to conceive a grown-up picture.

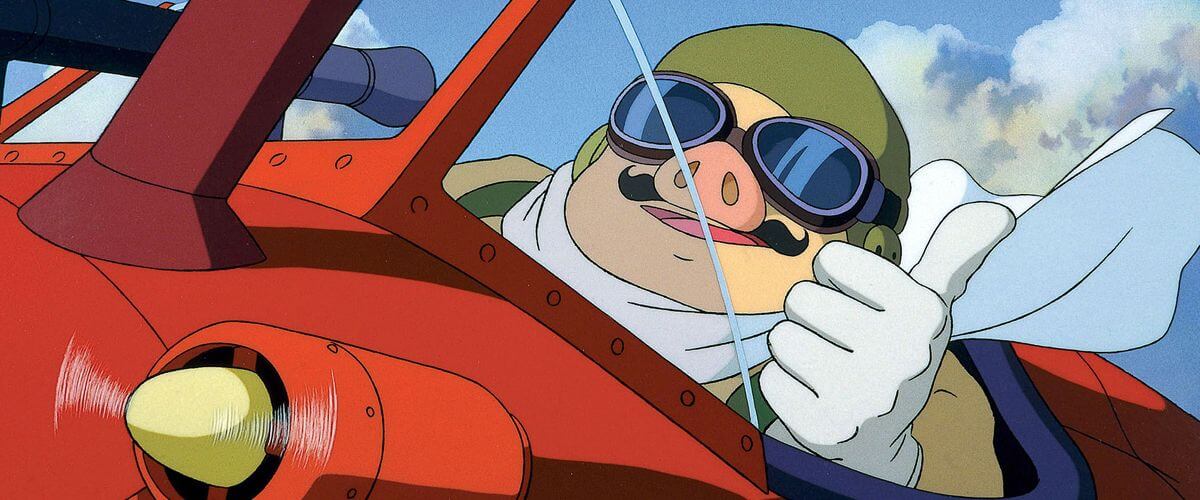

The story takes place between the two World Wars, around the early 1930s. A mysterious spell transformed Italian flying ace Porco Rosso, whose name means “Crimson Pig”, into a mixed creature. He’s filled out with a round middle-aged body and the face of a swine, and the look is completed with a Red Baron mustache. Even though he’s of the porcine persuasion, he’s no Porky Pig; this pilot smokes cigarettes, drinks wine, and lightly swears, pushing the PG-rated envelope. Had Errol Flynn been Italian instead of Tasmanian, much shorter, eighty pounds heavier, and a pig, then you might have something like Porco, an adventurous romantic at heart no matter how stubborn he may seem. Since Porco’s transformation, he’s given up working for one side; he makes his living collecting bounties on sky pirates in the region of the Adriatic Sea, maneuvering his unique red plane through exciting mid-air combat. When off duty, he takes leave on a picturesque secluded isle.

The story takes place between the two World Wars, around the early 1930s. A mysterious spell transformed Italian flying ace Porco Rosso, whose name means “Crimson Pig”, into a mixed creature. He’s filled out with a round middle-aged body and the face of a swine, and the look is completed with a Red Baron mustache. Even though he’s of the porcine persuasion, he’s no Porky Pig; this pilot smokes cigarettes, drinks wine, and lightly swears, pushing the PG-rated envelope. Had Errol Flynn been Italian instead of Tasmanian, much shorter, eighty pounds heavier, and a pig, then you might have something like Porco, an adventurous romantic at heart no matter how stubborn he may seem. Since Porco’s transformation, he’s given up working for one side; he makes his living collecting bounties on sky pirates in the region of the Adriatic Sea, maneuvering his unique red plane through exciting mid-air combat. When off duty, he takes leave on a picturesque secluded isle.

After clipping the wings of the Mamma Aiuto gang, a crusty sky pirate clan, Porco visits his favorite nightspot, the Hotel Adriano, home of the dishy Gina. She doubles as Rick from Casablanca with her mysterious nightclub owner airs, only instead of a plucky piano player, she sings sexy French ballads. Having watched plenty of good pilots take nosedives into the sea, she watches over Porco, hoping for an unlikely love to spring. Meanwhile, the various pirate gangs band together as the Pirates of the Adriatic, joining with Curtis, a cocky Texan determined to take Porco down and marry Gina. Indeed, Curtis shoots Porco’s plane out of the sky, sending the now-in-hiding pig pilot to Milan, where his mechanic will reassemble what’s left of the bird. There, Porco’s longtime mechanic Piccolo insists that a young girl, Fio, design and assemble the new plane. Fio is Miyazaki’s strong-headed tomboy who surprises everyone with her skills in aircraft engineering. These Milan scenes are the most autobiographical in the film. Miyazaki’s father oversaw operations at Miyazaki Airplane, a parts factory owned by the director’s uncle; his childhood was filled with imagined aviation devices sketched onto paper, particularly the A6M Zero fighter. He drew human flight or flying machines because, unlike his three brothers, he was sickly and made to remain home with his mother, to whom he bonded and later reflected in his female protagonists.

Piccolo S.P.A., where Porco takes his plane, constructs airplanes in a small neighborhood workshop, a family business, versus a factory of mindless automatons without an inkling of imagination. “Well, then,” Piccolo announces, “Let’s load up on the grub so we can work like bees.” This mirrors Miyazaki’s own approach toward animation: Studio Ghibli was the parallel where hard work was mandatory, and where Miyazaki was a confirmed workaholic (it’s no wonder Porco’s new engine is a “Ghibli” brand). Because their husbands are working in far-off cities, the plane is assembled by local women, all underestimated by Porco—none more than his designer Fio. But what can you expect from a pig? “All middle-aged men are pigs,” Porco warns young Fio, who’s developed something of a crush on him. Porco’s cynical characterization presents a deceptively simple metaphor, which Miyazaki no doubt hoped would sink into the collective unconscious of those tired businessmen on the flight home. The hero reminds people “I’m a pig” as if explaining away his character flaws, by both identifying his obvious physical malady and also saying something about himself. He’s a sexist in his attitude toward women, expressing his chauvinism when he says no to women building his plane. And yet, he’s clearly conflicted. As a bounty hunter, he’s unpatriotic and apolitical; however, he claims he’d rather be a pig than a fascist. And then there’s his curse—there’s no explanation as to who put it on him or why; just a general feeling that once he does something honorable again he’ll cease to look like a pig.

The finale plays out in very traditional cartoon language. Conflicts are resolved through a head-to-head dogfight competition between Porco and Curtis, wherein the rewards are either Fio’s hand in marriage or a bundle of cash (complete with a dollar sign on the bag). These touches emphasize Miyazaki’s fun-loving intentions, leaving the audience wrapped up in a seemingly effortless conflict that’s resolved through blithe and comedic exploits. It’s all animated with the filmmaker’s singular touch, clean lines stylized for the period, and boasting incredible European details throughout.

The finale plays out in very traditional cartoon language. Conflicts are resolved through a head-to-head dogfight competition between Porco and Curtis, wherein the rewards are either Fio’s hand in marriage or a bundle of cash (complete with a dollar sign on the bag). These touches emphasize Miyazaki’s fun-loving intentions, leaving the audience wrapped up in a seemingly effortless conflict that’s resolved through blithe and comedic exploits. It’s all animated with the filmmaker’s singular touch, clean lines stylized for the period, and boasting incredible European details throughout.

Released in 1992, like most Miyazaki films Porco Rosso did splendidly in Japan. For the French release, Studio Canal hired rugged-voiced actor Jean Reno to bring life to their Porco, whereas Walt Disney’s 2003 dub gave Michael Keaton the job. Keaton perfectly captures the character, giving Porco deep and human flourishes. Other voicework in the U.S. dub includes actors Cary Elwes as Curtis, Brad Garrett as the pirate boss, Susan Egan as Gina, and Kimberly Williams-Paisley as Fio. Not as straightforward or family oriented as Miyazaki’s other works, the film has been regrettably overlooked by U.S. audiences in favor of more popular titles like Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away. Porco Rosso remains Miyazaki’s most undervalued work. Comprised of engaging period aesthetics and dashing adventure, the film is often considered peculiar for the bizarre mixture of setting and pig-centric concept. Even Miyazaki admitted, “Why kids love it is a mystery to me.” But its presentation remains as purely enjoyable as anything bearing the director’s name. The characters, though distant in the same illusory way that the characters from Casablanca attempt to disguise their feelings, come alive by the finale in crowd-pleasing form, whereas the thrilling dogfight sequences recall those from Hell’s Angels. Providing the most plainly escapist effort in Miyazaki’s filmography, this joyous film never ceases to entertain.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review