Poor Things

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published on November 15, 2023, for DFR’s Patreon community.

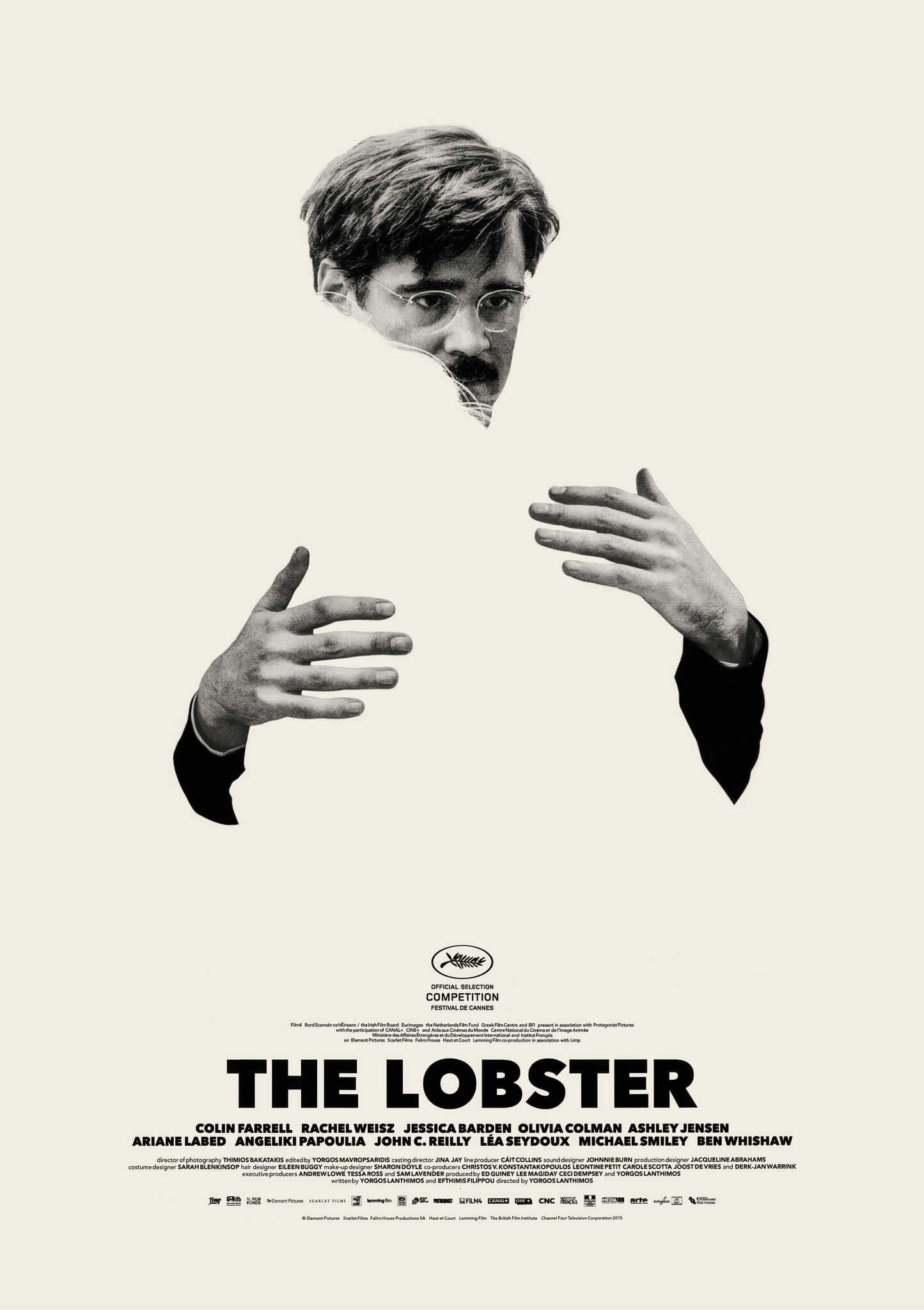

Yorgos Lanthimos chisels away at the artifice of polite society in Poor Things, an uninhibited and delightfully grotesque feature about how the civilizing process stifles personal freedoms, introduces shame, and suppresses natural bodily processes and desires. Set in an alternate Victorian London, the film begins with notes of Georges Méliès’ fantastical silent-era cinema blended with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, but soon it resembles a steampunk dreamscape visualized by Terry Gilliam and thematically loaded with female empowerment. At the center is Emma Stone, giving a liberated, primal performance as the reanimated creation of the resident mad scientist, who took the brain of a pregnant suicide victim’s unborn baby and placed it inside the mother’s adult body. From this launchpad, Lanthimos shoots for the moon, exploring the many pleasures and degradations that make us human, even though the culture at large may consider them taboo to discuss or depict. Similar to his efforts in Dogtooth (2009) and The Lobster (2015), the Greek writer-director considers how society conditions people, especially women, over the course of youth and adolescence, to curb innate responses and curiosities. Wildly funny, visually inspired, and thematically ambitious enough to warrant a sensory overload, Poor Things is a virtuosic and sensational wonder.

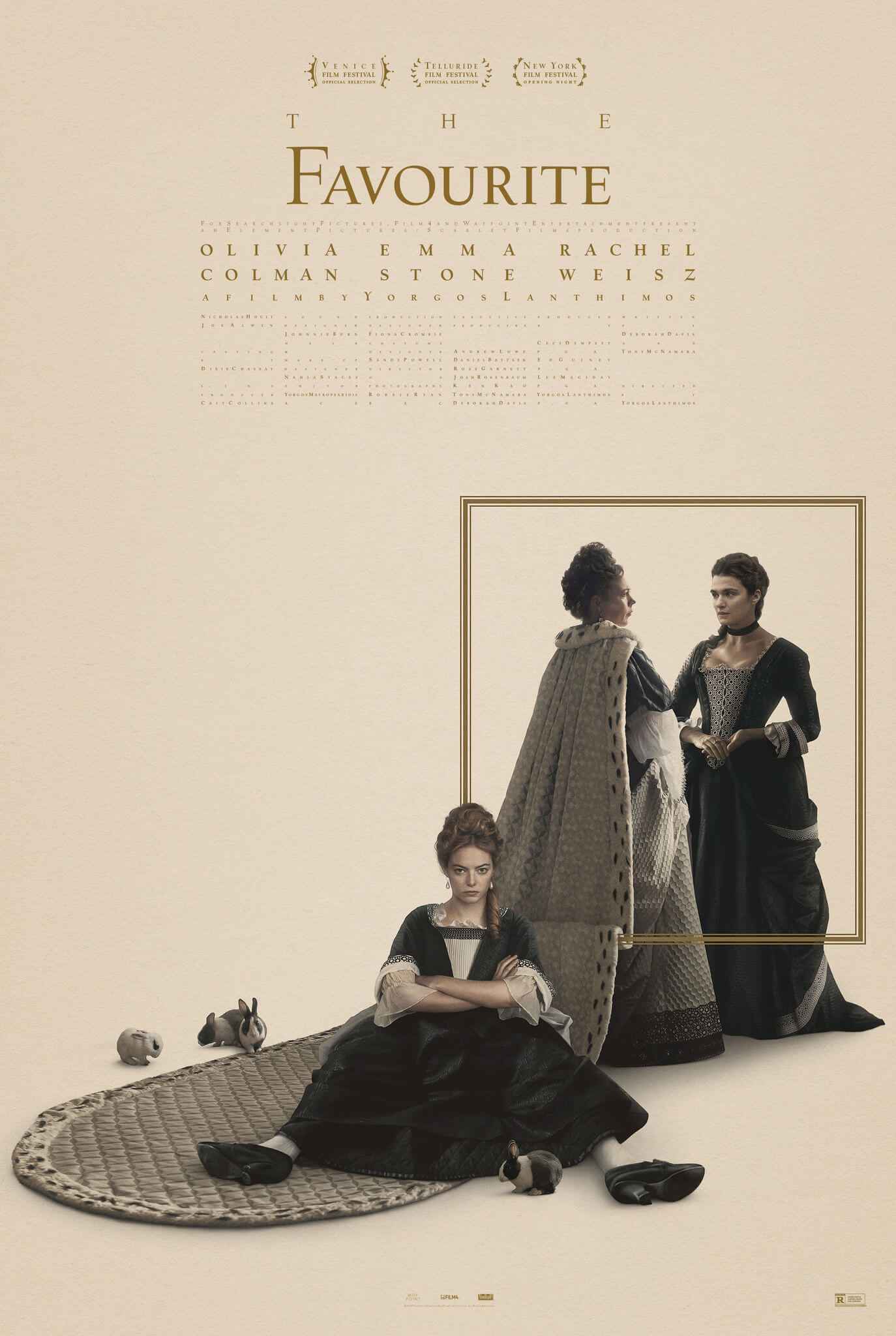

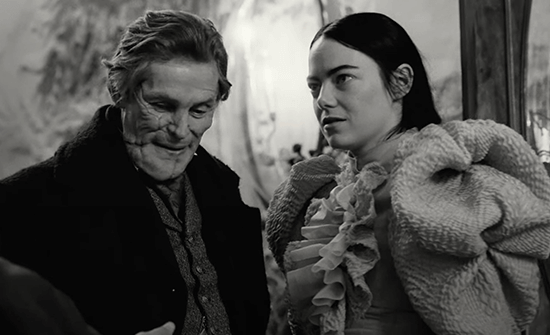

Reteaming with screenwriter Tony McNamara, co-writer of The Favourite (2018), Lanthimos adapts Alasdair Gray’s 1992 book Poor Things: Episodes from the Early Life of Archibald McCandless M.D., Scottish Public Health Officer. From the outset, those versed in the director’s recent work, including The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017), will recognize the familiar use of wide-angle lenses and probing camerawork by cinematographer Robbie Ryan. But that’s about where the visual comparisons end; Lanthimos has never been so explicit in visualizing his parables in expressive terms. In his earlier work, no matter how surreal his subject matter or the behaviors of his characters become, their surroundings appear relatively normal. Not so in Poor Things. Situated in a fictional version of London with nineteenth-century costumes, the film’s candy-colored world boasts zeppelins, elevated trams, and a steam-operated carriage with a horse head mounted on the front. Outside, the architecture looks like Antoni Gaudí by way of Robert Wiene, with organic shapes and expressionistic angles. Inside the estate of the resident Dr. Frankenstein, known as Dr. Baxter (Willem Dafoe), the grounds are populated by his twisted animal experiments, such as a goose head sewn onto a dog’s body and vice versa. Nothing appears natural in this world that desperately tries to suppress natural feelings.

This is true of Bella Baxter (Stone) as well, the creation of Dr. Baxter, whose students call him a “monster,” but he prefers “God,” short for Godwin. Baxter is a curious case; he has been visibly scarred by his surgeon father. Now he looks like Mason Verger from Hannibal (2000) and has a mind full of disturbing memories about his father’s many abuses—besides being turned into a eunuch, he also has a gastronomical malady that requires him to belch a floating bubble out of his throat mid-meal—and he casually doles out descriptions of his trauma matter-of-factly to his young apprentice, Max McCandles (Ramy Youssef). When Max arrives in Baxter’s employ, he sees Bella as a simpleton, smashing plates, urinating on the floor, and masturbating without reserve. “What a very lovely retard,” he observes, before Baxter explains that he fished Bella, formerly Victoria, out of the river and replaced her brain with that of her baby’s. “She’s an experiment,” Baxter explains, “and I must control the conditions, or the results will not be pure.”

This is true of Bella Baxter (Stone) as well, the creation of Dr. Baxter, whose students call him a “monster,” but he prefers “God,” short for Godwin. Baxter is a curious case; he has been visibly scarred by his surgeon father. Now he looks like Mason Verger from Hannibal (2000) and has a mind full of disturbing memories about his father’s many abuses—besides being turned into a eunuch, he also has a gastronomical malady that requires him to belch a floating bubble out of his throat mid-meal—and he casually doles out descriptions of his trauma matter-of-factly to his young apprentice, Max McCandles (Ramy Youssef). When Max arrives in Baxter’s employ, he sees Bella as a simpleton, smashing plates, urinating on the floor, and masturbating without reserve. “What a very lovely retard,” he observes, before Baxter explains that he fished Bella, formerly Victoria, out of the river and replaced her brain with that of her baby’s. “She’s an experiment,” Baxter explains, “and I must control the conditions, or the results will not be pure.”

But Bella has no problem with purity. She’s driven, like an infant, by pure id—an agent of unfiltered instinct and desire usually contained within a small, immobile body. Put those drives into a mature adult body, and the result becomes disturbing, hilarious, and a sharp commentary on social learning. At first, Bella, who has a toddler’s understanding of speech, is a destructive, violent presence. She pushes a dinner plate off the table just to hear it shatter. When Max shows her a frog, her first instinct is to smash it. She wanders around Dr. Baxter’s laboratory, where he conducts dubious experiments on cadavers, and she takes a scalpel to the eyes of one, announcing with maniacal glee, “Squish, squish, squish!” Despite having the brain of a child, she is not a baby’s mind in an adult body. She’s an aberration, a literary monster, allowing her mind, language skills, emotions, and intellect to advance quickly, perhaps mirrored by her rapid two-inches-a-day hair growth—recalling what Tyrell tells Roy in Blade Runner (1982): “The light that burns twice as bright burns half as long.”

But after discovering how to masturbate, her preoccupation is sexual gratification. She grabs at the maid’s “hairy business” to demonstrate the genuine pleasure of self-gratification for her, but Dr. Baxter tells her, “In polite society, this is not done.” She would prefer to spend her days “working on myself to achieve happiness,” and she can’t understand why she should suppress or deny those feelings. Take when she dances later, and she moves with wild gyrations, following how her body responds to the music, not according to some prudish dance with steps that adhere to decorum—she is unfiltered by the limitations of civilization. Meanwhile, Baxter attempts to arrange a marriage between Bella and Max. However, Duncan Wedderburn, an absurd gentleman and “pretty moron,” woos her into bed and warns her that marriage may imprison her, so he convinces her to run away with him to Lisbon. He is played by a lusty Mark Ruffalo, who is riotous as a foppish example of the enlightened class, his hangups pathetic, petty, and absurdist.

Gradually, the initial shock of Poor Things’ setup and unbridled raunchiness gives way to a fairy tale about Bella’s personal growth. Arranged in chapters, such as “The Ship” or “Paris,” Lanthimos constructs an adventure of self-discovery and actualization. It’s like a storybook wherein, instead of contending with three bears or seven dwarfs, the female protagonist learns the art of “furious jumping,” works in a Parisian brothel, reads voraciously, and later considers marriage before learning about her original identity. A key encounter happens on the ship from Lisbon to Paris, where Bella meets Martha (Hanna Schygulla, the German legend and muse of Rainer Werner Fassbinder), who reads philosophy and encourages Bella to do the same. Joined by cynical thinker Harry Astley (Jerrod Carmichael), Martha instills an independent streak in Bella, prompting her to ask questions. For example, if Duncan has money and homeless people do not, why shouldn’t he give them what he has? Her fissure with Duncan over such questions soon finds Bella looking for work in a Parisian brothel, where she learns the sex that she so enjoys can earn her a living but isn’t always good. Still, she resolves to become her own means of production, which she tells Duncan, and then finds herself in a romance with a fellow sex worker, Toinette (Suzy Bemba).

Gradually, the initial shock of Poor Things’ setup and unbridled raunchiness gives way to a fairy tale about Bella’s personal growth. Arranged in chapters, such as “The Ship” or “Paris,” Lanthimos constructs an adventure of self-discovery and actualization. It’s like a storybook wherein, instead of contending with three bears or seven dwarfs, the female protagonist learns the art of “furious jumping,” works in a Parisian brothel, reads voraciously, and later considers marriage before learning about her original identity. A key encounter happens on the ship from Lisbon to Paris, where Bella meets Martha (Hanna Schygulla, the German legend and muse of Rainer Werner Fassbinder), who reads philosophy and encourages Bella to do the same. Joined by cynical thinker Harry Astley (Jerrod Carmichael), Martha instills an independent streak in Bella, prompting her to ask questions. For example, if Duncan has money and homeless people do not, why shouldn’t he give them what he has? Her fissure with Duncan over such questions soon finds Bella looking for work in a Parisian brothel, where she learns the sex that she so enjoys can earn her a living but isn’t always good. Still, she resolves to become her own means of production, which she tells Duncan, and then finds herself in a romance with a fellow sex worker, Toinette (Suzy Bemba).

In every visual choice, Lanthimos avoids characterizing Poor Things as a mere period piece or sci-fi escapade; instead, he dreams up a symbolically loaded psychosexual awakening. If The Favourite had a modern bent stemming from its occasional offbeat behaviors, Poor Things’ anachronisms remain a constant source of wonder, oddity, and befuddled hilarity. The costumes designed by Holly Waddington blend Victorian styles with artificial components, such as latex, creating a look not only out of time but also reminiscent of genitalia and prophylactics. Musician Jerskin Fendrix supplies his first film score, an array of almost discordant strings that nonetheless feel harmonious in this context. Production designers Shona Heath and James Price create retrofuturist spaces that borrow from classical paintings, historic interiors, and the imaginations of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. Even the CGI avoids any attempt at naturalism, distorting reality so that the skies resemble the evocative backdrops from The City of Lost Children (1995) or Life of Pi (2012), suggesting the whole world is seen through Bella’s eyes—enhanced by the subjectivity of someone newly processing everything around her. As a result, watching Poor Things feels like a cinematic deluge in the most sublime ways.

Maybe it’s her so-called father’s influence, but Bella’s curiosity about experience, economic disparity, and sex in all its forms, ranging from ecstasy to discomfort to appease her customers, becomes tantamount to scientific curiosity. Beyond the film’s graphic but often funny sex scenes—which never attempt sheer eroticism, only an appropriately detached quality, as though the viewer is watching Bella as a case study—the narrative becomes one of fulfillment in the face of societal limitations. Duncan and other patriarchal men attempt to keep Bella under their control and exploit her, whereas Dr. Baxter and even her brief fiancé Max encourage her inquisitiveness. Max’s openness to Bella’s personal freedom extends to offering no complaints when she runs off with her body’s former husband, General Alfie Blessington (Christopher Abbott), a cruel man who torments his staff with a pistol and intends to circumcise Bella into submission. As both her original identity and the mother-daughter amalgam that is Bella, she experiences oppression from characters such as Duncan and Blessington. Her arch reaches a point of rebellion when she finally becomes an experimenter—like her sickly, mangled creator—who’s not opposed to playing mix-n-match with cranial organs to disturbingly hilarious effect.

Given the film’s nineteenth-century setting and formal arrangement, it’s worth considering to what extent Lanthimos intends Poor Things as a metaphor that equates Bella’s existential journey to the development of motion pictures over time. Consider the earliest scenes in black-and-white, with images and irises typical for the silent era. What initially feels like a throwback soon begins to expand stylistically as Bella’s personhood blooms, accenting Ryan’s use of wide angles and fluid camera movements with heightened colors. Bella’s experience begins as simplistic and rooted in base desire, but gradually, she becomes interested in more than sex or momentary pleasures. This echoes how cinema went from peep-show kinetoscopes in the late 1890s to vaudeville and nickelodeon theaters in the early twentieth century. Soon, they developed into full-fledged features in movie houses across the world, with a studio infrastructure that told increasingly sophisticated narratives beyond momentary delights, incorporating new technologies such as sound and color. By the end of Poor Things, Bella has matured and claimed her independence, grown more worldly, and yet she remains curious. Perhaps this is Lanthimos’ dream for contemporary cinema as well.

Given the film’s nineteenth-century setting and formal arrangement, it’s worth considering to what extent Lanthimos intends Poor Things as a metaphor that equates Bella’s existential journey to the development of motion pictures over time. Consider the earliest scenes in black-and-white, with images and irises typical for the silent era. What initially feels like a throwback soon begins to expand stylistically as Bella’s personhood blooms, accenting Ryan’s use of wide angles and fluid camera movements with heightened colors. Bella’s experience begins as simplistic and rooted in base desire, but gradually, she becomes interested in more than sex or momentary pleasures. This echoes how cinema went from peep-show kinetoscopes in the late 1890s to vaudeville and nickelodeon theaters in the early twentieth century. Soon, they developed into full-fledged features in movie houses across the world, with a studio infrastructure that told increasingly sophisticated narratives beyond momentary delights, incorporating new technologies such as sound and color. By the end of Poor Things, Bella has matured and claimed her independence, grown more worldly, and yet she remains curious. Perhaps this is Lanthimos’ dream for contemporary cinema as well.

Poor Things is Lanthimos’ best film, and given his superb output since breaking out with Dogtooth, that’s no minor accomplishment. Wacky but smart, and assembled with inspired filmmaking that makes every scene worth pouring over its details, the film is a marvel. As Dr. Baxter, aka God, observes when he dies, “It’s all very interesting.” That’s an understatement. A committed performance from Stone, her best yet, enriches this world in a ceaselessly funny role that defies shame, the capitalistic push to accumulate and preserve wealth, and the social need to conform. Ever questioning the internal dynamics of families, romantic relationships, and social hierarchies, the director’s latest targets the pretense of civilization, which attempts to constrain and limit personal freedoms, especially for women, and creative drives according to its narrow limitations. (“Polite society will destroy you,” warns Astley. “We are a fucked species.”) However serious this theme may be, it’s contained within an unforced film of delightful excess that leaves the viewer exhausted, if not light-headed, from so much laughter. It’s an exaggerated film that grapples with heavy themes in heightened, decidedly surreal metaphorical terms that will test not only a viewer’s limits but also their ability to negotiate between what is represented and its intended meaning. But the greatest cinema challenges us, and Lanthimos never hesitates to confront his audience.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review