Pitch Black

By Brian Eggert |

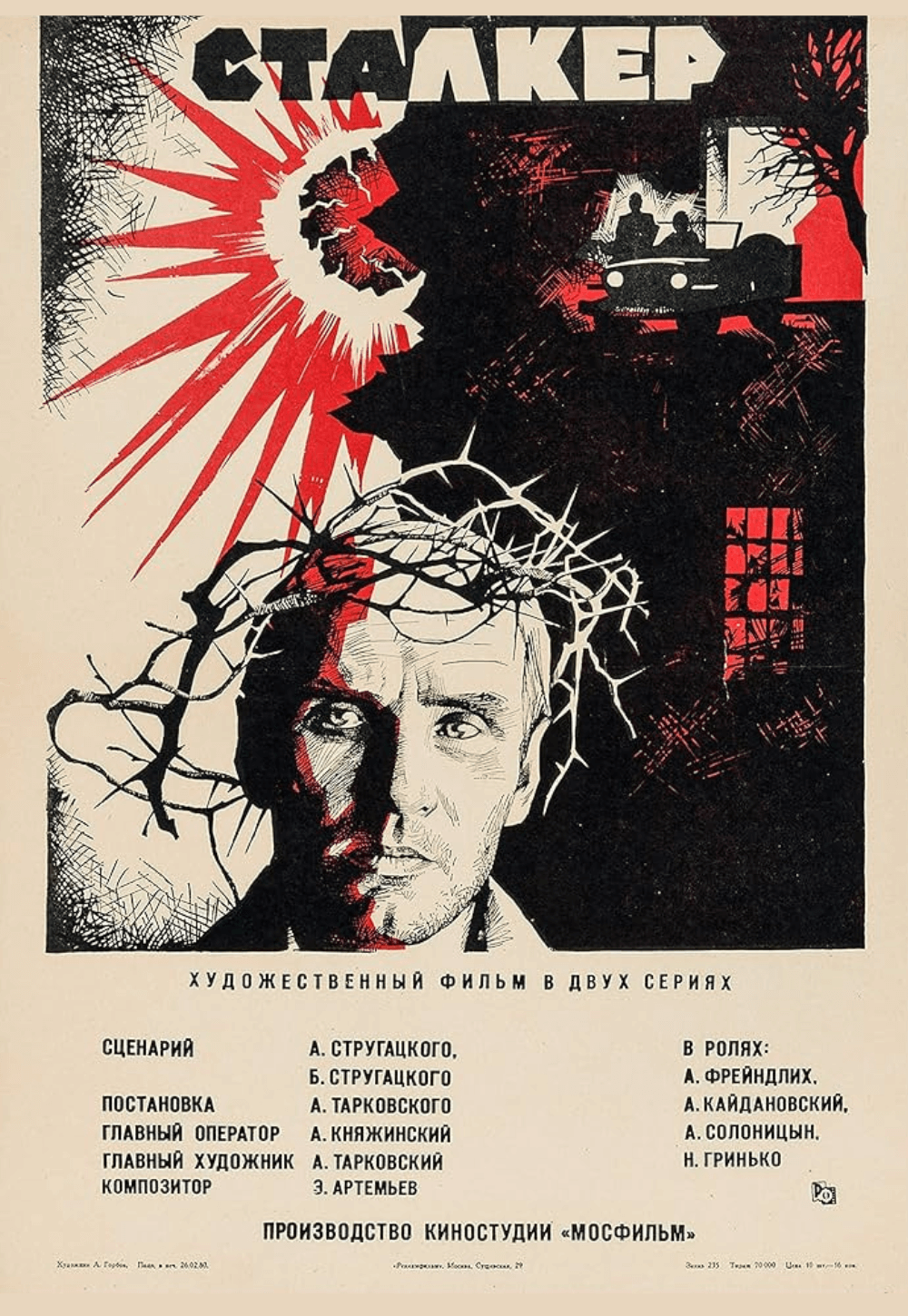

Practitioner of guilty pleasure B-movies—such as 1996’s underrated alien invasion yarn The Arrival—director David Twohy made Pitch Black in 2000, and it has since earned a cult following. The last film produced by PolyGram Filmed Entertainment, the production was completed for $23 million, and it more than doubled its returns at the worldwide box office. Its modest performance nonetheless announced the arrival of Vin Diesel’s action hero stardom; before this and Boiler Room (released on the same day as Pitch Black), Diesel’s notable credits consisted of only a small supporting role in Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1998) and voicework on Brad Bird’s animated gem The Iron Giant (1999). Twohy’s movie didn’t make Diesel a household name, but it’s something both he and his fans have returned to over the years. Many discovered Pitch Black on home video, while Diesel later teamed with Twohy to continue the adventures of the movie’s anti-hero, Riddick.

Jim and Ken Wheat wrote the screenplay along with Twohy, and the result derives influence from every notable sci-fi classic of the last fifty years. The movie opens with a spacecraft moving steadily through the blackness of space, recalling those iconic shots from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and later Star Wars (1977). Space debris penetrates the hull, and the craft begins to descend into the atmosphere of a nearby planet. With the captain killed in the chaos, pilot Carolyn Fry (Radha Mitchell) considers jettisoning some forty passengers in cryo-sleep so she might survive. She doesn’t, and in the ensuing crash, less than a dozen make it. Among the survivors are the Muslim Imam (Keith David), the would-be cop Johns (Cole Hauser), a boy named Jack (Rhiana Griffith), the antiquities dealer Ogilvie (Lewis Fitz-Gerald), and a detained killer named Richard B. Riddick (Diesel).

Stranded on a desert planet that has three suns and perpetual sunlight, the survivors pool their resources and head out into the surrounding nothingness to search for water. But the search becomes secondary after the escape of Riddick, a killer whose murderous ways are confirmed by Johns and never denied in Riddick’s monosyllabic retorts. Still, we know he’s the hero because he’s the one narrating. He’s eventually caught after one of the survivors mysteriously dies, although he insists he’s not responsible. “All you people are so scared of me.” Diesel’s character rumbles. “Most days, I’d take that as a compliment. But it ain’t me you gotta worry about now.” Indeed, traveling with Riddick as their captive, they come upon a leftover science camp in which they find no signs of human life—but they do find large, carnivorous, nocturnal batlike creatures that remain hidden in a web of underground tunnels. Worse, as the camp’s former geologists learned, they’re about to witness a planetary eclipse that only occurs every 22 years and lasts nearly a month, meaning the dark-dwelling creatures can finally emerge from their slumber to feed.

This nonsensical but otherwise intriguing idea comes with plenty of scientific questions, such as how do these creatures survive a 22-year hibernation period? In his review, Roger Ebert questions how such constant volcanic warmth from three suns would allow animals to survive on the planet at all. These questions are unavoidable but pointless for the material, as the setup is primarily a thorny series of potboiler circumstances designed to give the characters something to argue about. And what works best about Pitch Black are the characters—they’re actually interesting, or at least the actors are. The always reliable Mitchell was little-known in 2000, this being the first of her many B-movie appearances from Silent Hill to Rogue. Hauser swaggers in his brash arrogance, his villainous bounty hunter almost as hateful as his high-school bully roles from School Ties and Dazed and Confused. David is always solid in a genre movie supporter (see John Carpenter’s The Thing or They Live), and Griffith’s character comes with an unexpected surprise.

Pitch Black isn’t just a battle between baddies: Riddick vs. Aliens. Twohy and the Wheats make clear nods to Alien as their characters relate to one another while vile monsters take them down one-by-one. Mitchell’s character arc is a less compelling version of Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley; she’s a conflicted and involving character we care about. Still, this is Diesel’s show. Following other nihilistic anti-heroes such as Escape from New York’s Snake Plissken, the muscle-bound Riddick is always smarter, tougher, and badassier that anyone else onscreen. Of course, his larger-than-life character isn’t as evil as Johns suggests; instead, he’s the kind of incorrigible anti-hero who only exists in comic books and post-apocalyptic fiction. This human-franchise-in-the-making comes equipped with blades and goggles to protect his see-in-the-dark eyes—a feature Riddick opted for after his sentence in an underground prison, and which comes in handy once the eclipse beckons hordes of hissing creatures. Even the boy Jack thinks Riddick is immediately cool and, charmingly, adopts Riddick’s trademarked goggles and tough guy attitude for the remainder of the movie.

But no matter how many better movies Pitch Black borrows from, this entertaining little sci-fi/horror exercise is just good enough to keep its audience diverted for its runtime. Twohy has some impressive visuals in his bag, especially after the lights go out and the humans begin scrambling for a light source. Lame are the grayed alien POV images and Riddick’s purple night vision shots, both perspectives rendered using cheap-looking CGI. The alien creatures also look silly, the special FX having dated badly since the movie’s release. But then, this isn’t a movie about spatial science, aliens, or even the ever-increasing body count. Pitch Black is about how Twohy makes stereotypical characters come alive, in part because of his effective casting, and in part because he takes his time setting up the effective thrills. Another filmmaker wouldn’t have waited an hour to shut off the lights and start the killing. Twohy bides his time, develops his cast, and then unleashes hell upon them. Brainless though it may be, it’s the kind of guilty pleasure at which Twohy specializes.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review