Phoenix

By Brian Eggert |

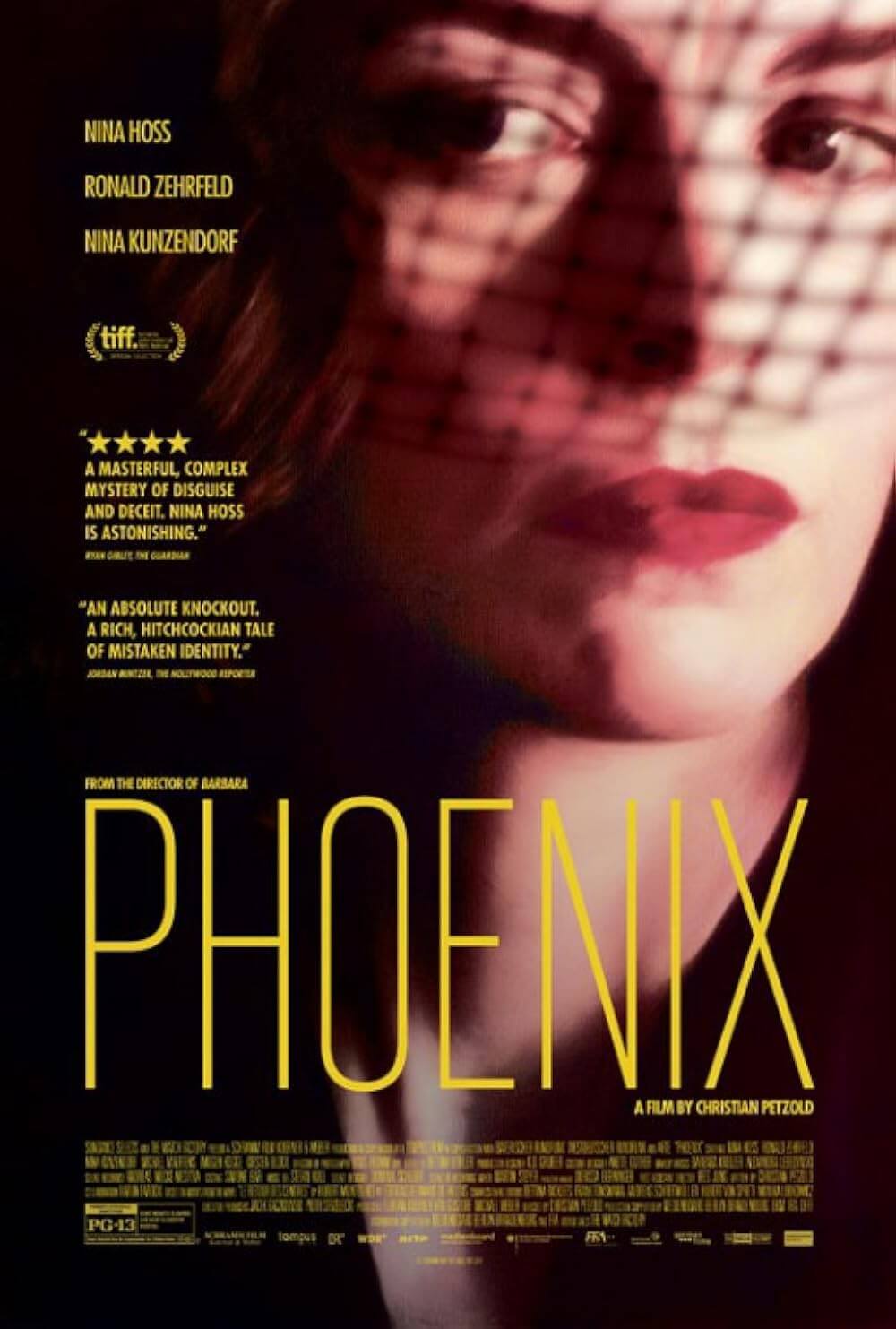

Phoenix opens as a car approaches an American border patrol in Germany after the end of World War II. Inside, an employee of the Hall of Jewish Records drives a mysterious passenger. The passenger’s face is hidden, wrapped up like the Invisible Man except for the blood that has soaked through the bandages. The driver explains to the suspicious soldier, who’s looking for Nazis trying to cross the border, that she’s an Auschwitz survivor. The soldier’s face goes blank and he lets them pass. And now we look again at the passenger and can only imagine what horrors she’s seen and endured. In Christian Petzold’s film, wartime atrocity changes people and leaves an inescapable mark. This enduring metaphor shapes and informs the film, which has earned comparisons to Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) and John Frankenheimer’s Seconds (1966) for its haunting representation of the relationship between physical and psychological identity.

Petzold collaborated with Harun Farocki on the script, based on the 1961 novel Le retour des cendres by French author Hubert Monteilhet. If the setup sounds familiar, director J. Lee Thompson (The Guns of Navarone and the original Cape Fear) helmed an adaptation of Monteilhet’s novel in 1965 called Return From the Ashes, starring Maximilian Schell, Ingrid Thulin, and a young Samantha Eggar. Thompson’s film was a melodramatic Hollywood picture of its era and hardly contained the raw emotion of Petzold’s film. The German filmmaker allows quiet, interior scenes to grow, and the viewer cannot help but saturate into the interior life of the protagonist, Nelly (Nina Hoss), whose disfigured face was shaped by a Nazi gunshot wound in Auschwitz. Her friend Lene (Nina Kunzendorf) takes her to a clinic where her face will be reconstructed. Though doctors advise her to pick a new face, just in case they cannot make her look exactly like her former self, Nelly was once a famous singer who depended on her looks and doesn’t want to be anyone else.

Just as the doctor warned, Nelly doesn’t look exactly like herself after her surgery wounds heal and her bandages come off. She looks off to herself somehow and feels that she’s ugly, that she can no longer be herself. She returns with Lene to Germany, hoping to reconnect with her former husband Johnny (Ronald Zehrfeld). Lene does not approve; after all, when Nelly was captured during the war, Johnny divorced her in order to keep in favor with the Gestapo. There’s also some question as to Johnny’s role in Nelly’s capture. Lene wants Nelly to come along with her to Palestine, where many Jewish survivors went after WWII, but Nelly believes there must be some good reason for Johnny’s actions and resolves to stay. She soon finds him working as a busboy in a club called “Phoenix” where, after she calls his name, he looks right through her and doesn’t recognize her. With her voice frail from the surgeries, her face different now, her hair color natural and face without makeup, she looks nothing like Johnny’s Nelly.

All at once, Johnny grabs her, assuming she’s a street urchin, and asks if she needs a job. He explains he’s after his dead wife’s inheritance and he wants her to play the role of Nelly to help him recover what he’s due. Johnny will teach her to walk, talk, write, and dress like his Nelly once did. As if in shock, she agrees to play this role for Johnny, who demands that he be called Johannes. Hoss’ performance is brilliant in these scenes, occupying the role of a damaged concentration camp survivor, betrayed wife, and unaware third party, all yearning for Johnny’s attention to varying degrees. When Nelly performs well, such as capturing her own signature, he’s impressed. But his behavior toward her appearance is very particular and she keeps getting things “wrong”—which speaks to Johnny’s image of Nelly. The implications of the scenes where he reshapes her say so much about the levels of their relationship before and after the war, as well as the faux relationship between Johnny and the person he believes is a willing participant in fraud. And each level on which their relationship operates has an important, metaphoric meaning.

All at once, Johnny grabs her, assuming she’s a street urchin, and asks if she needs a job. He explains he’s after his dead wife’s inheritance and he wants her to play the role of Nelly to help him recover what he’s due. Johnny will teach her to walk, talk, write, and dress like his Nelly once did. As if in shock, she agrees to play this role for Johnny, who demands that he be called Johannes. Hoss’ performance is brilliant in these scenes, occupying the role of a damaged concentration camp survivor, betrayed wife, and unaware third party, all yearning for Johnny’s attention to varying degrees. When Nelly performs well, such as capturing her own signature, he’s impressed. But his behavior toward her appearance is very particular and she keeps getting things “wrong”—which speaks to Johnny’s image of Nelly. The implications of the scenes where he reshapes her say so much about the levels of their relationship before and after the war, as well as the faux relationship between Johnny and the person he believes is a willing participant in fraud. And each level on which their relationship operates has an important, metaphoric meaning.

Films set amid the Black Markets and desperation of postwar Germany often find shady characters pushed to immoral limits. Petzold’s film doesn’t lose itself in the historical context or explore the crumbling postwar setting in detail outside of the narrative surrounding Nelly and Johnny. His rather economic runtime (98 minutes) concentrates on the characters and, for every frame, feels vital, not a moment wasted. The film builds to an incredible conclusion where Nelly asks Johnny to perform for some old friends—specifically, “Swing Low” with music by Kurt Weill and lyrics by Ogden Nash. This moment was not planned by Johnny and he seems apprehensive to start, seemingly because this woman cannot at first imitate his former wife’s voice. But then, quite symbolically, she finds her voice and, along with seeing her Auschwitz tattoo at this moment, Johnny realizes that the Nelly he’s constructed is the real Nelly. His look of utter shock, betrayal, fear, and shame is only matched by the wounded song of the film’s protagonist.

Hoss has starred in four of Petzold’s films, most recently 2012’s Barbara, in which Hoss and Zehrfeld also starred opposite each other. For that film, Petzold won the Silver Bear for Best Director at the Berlin Film Festival. Hoss also starred in Jerichow (2008) and Yella (2007) for Petzold, each time giving a performance of an emotionally punished character. She’s perfect as Nelly, a character whose identity has been stripped away literally and figuratively. She’s a shattered soul in early scenes after her recovery, broken and trying to find some way of putting herself back together. When she finds Johnny again, she’s forced to rebuild herself to realize his scheme. And as she becomes more like the old Nelly, she realizes not only how Johnny viewed her, but how much of a construction her former identity was. Moreover, she sees Johnny for what he is—which is just how Lene described him. Lene is a fascinating character too, and most haunted by the war; her psychological scar may be far deeper than Nelly’s physical ones.

Petzold’s direction is simple and natural, far removed from the expressive formal styles of Hitchcock and Frankenheimer in their respective films about a facial transmigration. In some ways, Phoenix could be described as a thriller, but there’s much more here that Petzold has to say about identity, how we see people, how people see us, and how time changes perspective. Critics who’ve been describing the film in conjunction with Vertigo latch on to the idea of a man shaping a woman’s appearance. But Petzold is less concerned about the fetishization of women than accessing the wounded, tragic emotional state of the film’s characters. This is a lean, affecting master class in classical filmmaking that somehow captures postwar shock in the first few scenes and continues on from there, delivering a perceptive and heartbreaking story that the viewer will want to watch again the instant it’s over. Distributed by IFC under its Sundance Selects label, Phoenix stands as one of 2015’s very best releases.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review