Philomena

By Brian Eggert |

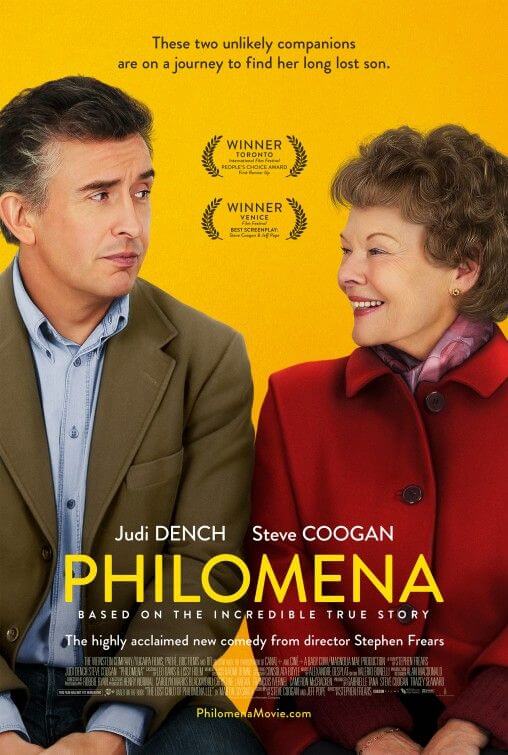

British comedian Steve Coogan has played a number of characters who are actors that wish to be taken seriously, but they rarely are. Art imitates life. In Hamlet II, Coogan played a failed drama teacher who writes a sequel to Shakespeare’s seminal work and delivers a musical about the meeting between Hamlet and Jesus. Coogan’s frequent collaborator Michael Winterbottom directed him in both Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story and The Trip, both in which he starred as a version of himself, and both in which he expressed a desire to get away from his famous Alan Partridge comic persona and break into dramatic Hollywood prestige films. Rather than trying to secure a part in an industry that has typecast him in humorous roles, Coogan resolved to produce, co-write alongside Jeff Pope, and star in Philomena, his own award-worthy production based on the true story told by journalist Martin Sixsmith in his 2009 book, The Lost Child of Philomena Lee.

Directed by Stephen Frears—versatile helmer of The Queen, Chéri, and Tamara Drewe—the script plays to Coogan’s strength for dry humor but also showcases his dramatic talents, incorporating a sobering dose of moral outrage: First, about the practice of Irish Catholic abbeys where thousands of young pregnant girls found homes and paid penance through slave labor, only to have their babies taken from them and sold to American buyers; second, to a lesser degree, about the Reagan administration’s refusal to fund AIDS research because of its moral stance on the naïvely perceived homosexual cause. Not since Peter Mullan’s The Magdalene Sisters (2002) has the Catholic Church’s sexual repression been so potently charged, whereas the recent Dallas Buyers Club offers a more thorough take on misconceptions about AIDS.

Here, the indomitable Judi Dench plays Philomena, who, as a pregnant teenager (Sophie Kennedy Clark in flashbacks) in the early 1950s, sought refuge at the Roscrea convent. She gives birth to her child under the watch of nuns, who refuse to offer an anesthetic during her breeched birth so that she might suffer for the lusty pleasure of her sins. Over the next few years, Philomena could see her young boy Anthony for just one hour a day while on break from her laundry duties. In 1955, the nuns at Roscrea sold Anthony to a wealthy American family, and Philomena was prevented from finding him, the nuns conspiring to keep the young mothers away from their children. Now elderly and filled with regret, Philomena wants to find Anthony and know what came of him, know if he ever thought about her, and let him know she thinks about him every day. Enter Sixsmith, played by Coogan, who has just been sacked from his prestigious position at the BBC. When he hears about Philomena’s search, he turns up his nose at reducing himself to a “human interest story” but takes the job nevertheless, if only to keep busy. Sixsmith’s investigation leads him to the United States with Philomena alongside him.

Together they learn her son was renamed Michael Hess and eventually became Chief Legal Counsel for Ronald Regan and George H.W. Bush. Michael, a closeted homosexual, died of AIDS in 1995. In addition to being a mystery of sorts, the film is a “road movie” with elements of “fish-out-of-water” and “mismatched-pair” story structures. At the center is the dynamic between Dench and Coogan. Dench’s Philomena is simple and good-hearted; she’s god-fearing and full of innocent charms and decent manners. Her delightfully inexperienced courtesy is paired alongside Sixsmith’s atheism and snooty elitism. Coogan excels at playing a snob, sarcastic, and is gradually affected more and more by Philomena’s heartrending search for her son. These characters also represent the audience’s potential reactions when we discover how fully the church exploited young girls for profit ($1,000 per child). Philomena’s humanity brings forgiveness and a surprising degree of tolerance, but Sixsmith responds to the unrepentant nuns and, serving up a small dose of catharsis, condemns the church.

And while the film tips toward Sixsmith’s standpoint, therefore leaving the audience with a sense of indignation toward the church and Republican Party, who later shunned Hess, the quiet acceptance practiced by Philomena in Dench’s ranged performance is astounding and thoughtful. Coogan, realizing his aspirations to become a credible actor, delivers a wittily comic performance with grave layers, as the treasured Dench somehow manages to capture sadness and anger and forgiveness all in a single expression. Although Philomena itself is a feature-length “human interest story” in odd-couple format, Frears brings an effective eloquence to the proceedings by refusing to over-emphasize the more dramatic or emotional components of the story. The restrained realism and depth of the melodrama are perfectly balanced, altogether avoiding what could have easily become schmaltzy, audience-friendly fare. Instead, Philomena is an engaging, funny, and challenging story about immeasurable cruelty and the search for closure.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

As the season turns toward gratitude, I’m reminded how fortunate I am to have readers who return week after week to engage with Deep Focus Review’s independent film criticism. When in-depth writing about cinema grows rarer each year, your time and attention mean more than ever.

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your moviegoing—whether it’s context, insight, or simply a deeper appreciation of the art form—I invite you to consider supporting it. Your contributions help sustain the reviews and essays you read here, and they keep this space independent.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review