Phantom Thread

By Brian Eggert |

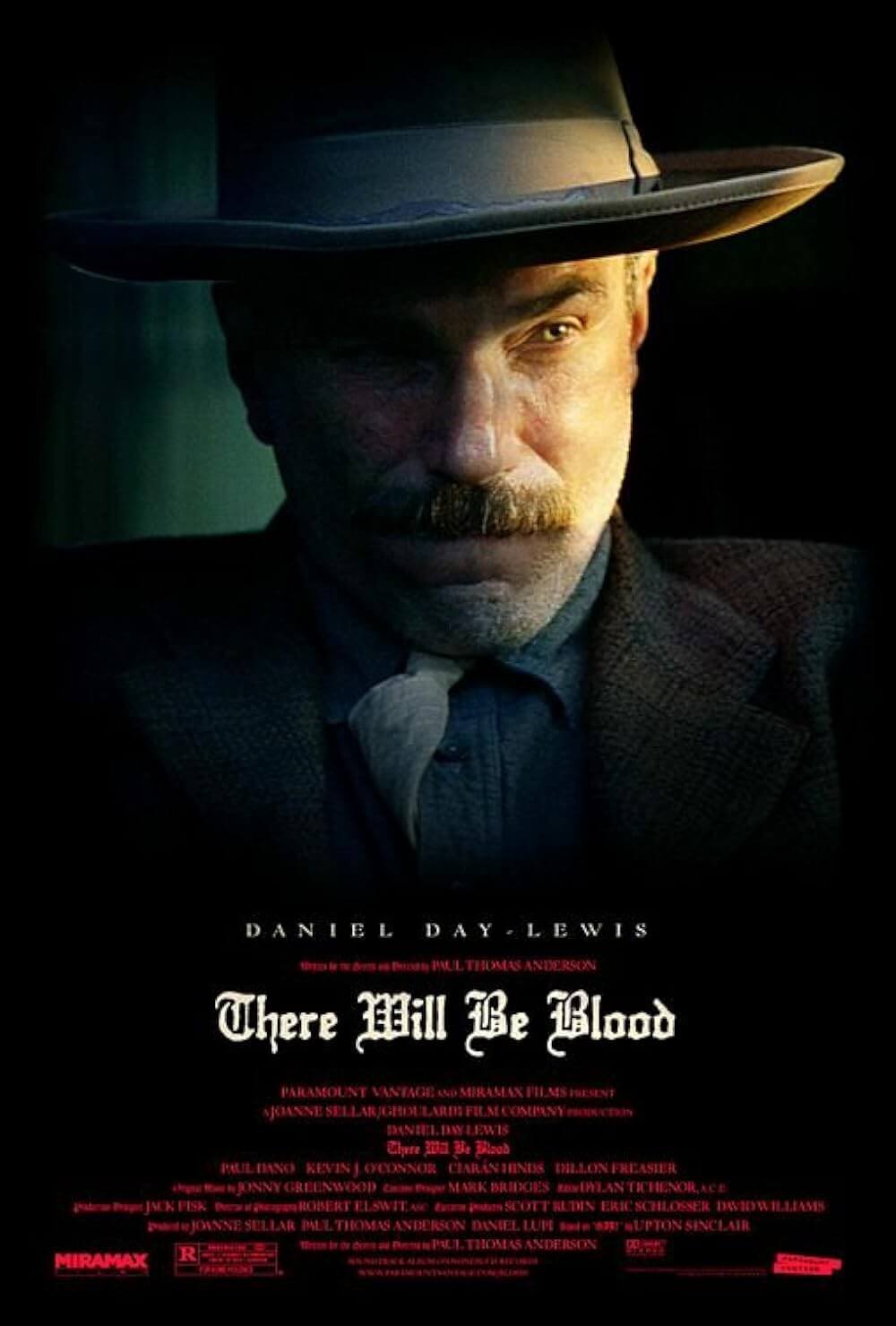

To master dressmaking, a designer must understand not only fashion but the practicalities of creating a garment, many of them unseen to the naked eye yet no less imperative. An untold number of fabrics each have a history, common uses, measured tenacity, and sheens. Each must be cut a particular way, then sewn together using a pattern that responds to the wearer’s mobility. The shape of the dress depends on the subject, their measurements, and body type. Color combinations, and whether they complement the wearer’s skin pallet, influence the look. Style is an entirely different matter, full of virtuosity and inspiration that cannot be taught. Such fine points require a meticulous personality and obsessive precision—characteristics that will, inevitably, emerge in the personal life and behaviors of the designer. Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread is a character study about a London dressmaker in 1955, whose exacting approach to his trade, while establishing his unparalleled reputation in European high couture, also fosters a hypercontrolled lifestyle. Reteaming with his There Will Be Blood (2007) star Daniel Day-Lewis, reportedly the actor’s final onscreen appearance, Anderson delivers a film in the hermetically sealed and paranoid world constructed by its designer. But even while deconstructing aspects of the designer’s life and his devotion to creating immaculate garments, Anderson’s film develops into a strange and complex, even unresolvable, love story.

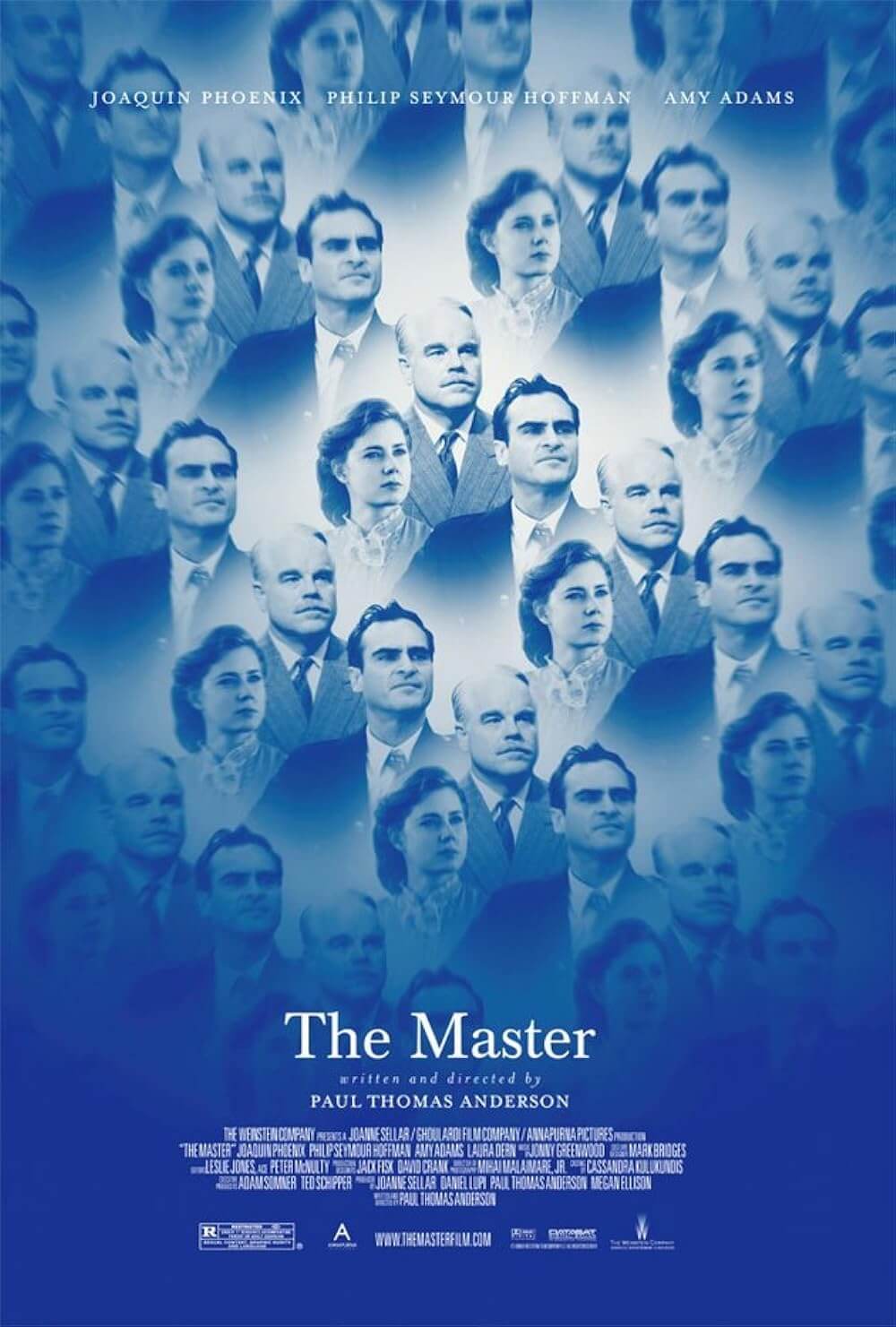

Inspired by both British-born couturier Charles James and Spanish designer Cristóbal Balenciaga (called “the master of us all” by Christian Dior), Anderson and an uncredited Day-Lewis worked together on the script for years, exchanging ideas about the central character, his obsessions and peculiarities. Day-Lewis came up with his character’s winking name, Reynolds Woodcock, whose regimented existence overcompensates almost as much as his eponym. He’s another cracked genius on par with Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood or Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Lancaster Dodd in Anderson’s 2012 film, The Master (and this film is as much of an accomplishment as those). Great beauty requires concentration, and his days are systematized to a routine that accommodates his clear head. Every morning his team of seamstresses arrives at his London home and studio to carry out his designs. His sister, Cyril (Lesley Manville), whom he refers to as “my old so-and-so,” manages his affairs, including his romances, shielding him from any unpleasantness or distractions. Any break in his routine causes him great ill. A mere annoyance early in the morning could put his entire day off-track. In one scene, unrequested tea arrives in his workroom; he demands its removal, and while the tea may be gone, he shouts, “The interruption is staying right here with me!” In cinema, unmovable men of this sort are usually destabilized and returned to reality by love.

Enter Alma (Vicky Krieps), a blushing young woman who serves Reynolds at a seaside hotel. Catching his eye with her “ideal” body type, Alma is amused by Reynolds’ voracious appetite. She agrees to dinner with the “hungry boy,” which may be the strangest first date in history: Reynolds insists on taking her measurements for a dress. What begins as a private moment becomes even more awkward as Cyril enters and begins to record her measurements, clearly as part of a routine that has been carried out with other women before. “You have no breasts,” he tells Alma. But before any embarrassment sets in, he adds, “You’re perfect.” The scene might suggest a thematic parallel with Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958)—which won’t be the last Hitchcock evocation in Phantom Thread—in which a private detective (Jimmy Stewart) grows fixated with recreating the object of his affection in another woman (both played by Kim Novak). Given how Reynolds obsesses over the particular look of a woman to satisfy his visual pleasure, Alma, proud of her ability to stand as long as Reynolds requires to complete a fitting, transforms into a willing muse.

Enter Alma (Vicky Krieps), a blushing young woman who serves Reynolds at a seaside hotel. Catching his eye with her “ideal” body type, Alma is amused by Reynolds’ voracious appetite. She agrees to dinner with the “hungry boy,” which may be the strangest first date in history: Reynolds insists on taking her measurements for a dress. What begins as a private moment becomes even more awkward as Cyril enters and begins to record her measurements, clearly as part of a routine that has been carried out with other women before. “You have no breasts,” he tells Alma. But before any embarrassment sets in, he adds, “You’re perfect.” The scene might suggest a thematic parallel with Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958)—which won’t be the last Hitchcock evocation in Phantom Thread—in which a private detective (Jimmy Stewart) grows fixated with recreating the object of his affection in another woman (both played by Kim Novak). Given how Reynolds obsesses over the particular look of a woman to satisfy his visual pleasure, Alma, proud of her ability to stand as long as Reynolds requires to complete a fitting, transforms into a willing muse.

Cyril, meanwhile, watches their romance develop, confident that she will once again be required to end her brother’s relationship. A hardened and controlled presence, Cyril makes her brother, ever the beleaguered and put-upon artist, look almost silly by comparison. She remains in the backdrop of most scenes, a keen presence who ensures everything goes according to her brother’s precise expectations and tastes, protecting his sensitive state of tranquility. It’s their livelihood, after all. She also humors her brother’s more eccentric whims because of his talent, but her devotion has limits. Take the scene where Reynolds snaps at her, and Cyril flatly states, “Don’t pick a fight with me, you certainly won’t come out alive. I’ll go right through you, and it’ll be you who ends up on the floor.” Altogether, the Woodcock siblings and Alma soon form a curious family that Anderson has openly admitted germinated with Hitchcock’s Rebecca. In that Gothic romance from 1940, Joan Fontaine plays the new wife of widower Laurence Olivier, whose domineering house matron, Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson), never allows the naïve young woman forget that she’s nothing more than an inadequate number two.

Regardless, Alma is not a passive figure, as Fontaine was. While the Woodcocks are seen from her perspective, she is more than a narrative device or entry-point into Reynolds’ world. She is deceptively complex, just not as overt as her counterparts. Consider how she seems determined to give Reynolds what he wants, but not in a doting way. Rather, she observes, tries to predict his needs, and proves unwavering to shocking extremes. She begins their relationship by remaining quiet, studying, and taking orders—yet she refuses to be a doormat. When Reynolds is rude or berating, as he often can be, she stands up for herself and willingly contradicts him. “I am trying to love him the way I want to,” she tells Cyril, refusing to fully submit to the Woodcocks’ demands. Alma may seem to be ornamentation to Reynolds in the beginning, but gradually Anderson reveals that Phantom Thread is her story—one that occupies the familiar tale of a woman who melts the icy heart of a devoted professional. She enjoys looking beautiful in Reynolds’ dresses and reveres his work, and she feels protective when other, admiring young women try to draw his gaze. At the same time, she refuses to bend to his stringent demands when they reach beyond her tolerance and, in due course, forces both Reynolds and Cyril to change to her demands.

Though much of the film involves Reynolds’ petulant behavior, this gives way to scenes of stunning theatricality in which the cast flourishes. Day-Lewis’ performance requires a self-seriousness that also captures the often hilarious absurdity of his character. His fastidiousness materializes in outbursts of peculiarity and cruelty, and while searing, his insults are also intentionally ridiculous, like those of a child, comically so. Watch Day-Lewis’ irritated face as Alma clinks her teen against a metal spoon. His anger over such a small annoyance has an over-the-top quality that emerges in other areas of the film as well. Manville performs in a state of restrained British discipline, often seen in her many collaborations with Mike Leigh. Krieps, the relative unknown, delivers the most mysterious turn of the three. Her Alma is compassionate, in some ways vulnerable, but capable of more than the others realize at first. Cyril begins to recognize, with some resentment, her edge early on, whereas Reynolds sees her genuine devotion in a sequence when a drunken benefactor (Harriet Sansom Harris) makes the error of behaving foolishly in one of his dresses. The entire two-hour-and-ten-minute runtime crescendos to the eventual union of Alma and Reynolds, but the route to this destination is indirect and never goes where the viewer expects.

Though much of the film involves Reynolds’ petulant behavior, this gives way to scenes of stunning theatricality in which the cast flourishes. Day-Lewis’ performance requires a self-seriousness that also captures the often hilarious absurdity of his character. His fastidiousness materializes in outbursts of peculiarity and cruelty, and while searing, his insults are also intentionally ridiculous, like those of a child, comically so. Watch Day-Lewis’ irritated face as Alma clinks her teen against a metal spoon. His anger over such a small annoyance has an over-the-top quality that emerges in other areas of the film as well. Manville performs in a state of restrained British discipline, often seen in her many collaborations with Mike Leigh. Krieps, the relative unknown, delivers the most mysterious turn of the three. Her Alma is compassionate, in some ways vulnerable, but capable of more than the others realize at first. Cyril begins to recognize, with some resentment, her edge early on, whereas Reynolds sees her genuine devotion in a sequence when a drunken benefactor (Harriet Sansom Harris) makes the error of behaving foolishly in one of his dresses. The entire two-hour-and-ten-minute runtime crescendos to the eventual union of Alma and Reynolds, but the route to this destination is indirect and never goes where the viewer expects.

Beneath the surface text, questions linger about Reynolds’ sexuality. His sexual appetites are relatively unexplored next to his demands as an eater. A scene in which Reynolds and Alma disappear behind his bedroom door represents their single onscreen sexual encounter, implied or otherwise. Still, a fashion designer is almost required to have a case of scopophilia, the love of looking. He looks at beautiful people adorned with gorgeous fabrics all day long, stopping for only a few short hours of sleep. For Reynolds, the height of eroticism comes during a private fashion show in his home. Alma models one of his gowns, while he remains behind closed doors, always away from his public, peering at her through a peephole. The shot mirrors one in Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), as the light through the opening illuminates Reynolds’ eye, just as it did for Norman Bates. Although voyeuristic elements inhabit Phantom Thread, Anderson never makes the material exploitative or turns it into a thriller. The film inhabits a romantic tradition, though its characters and narrative trajectory are uncommon, often signaled as such by Jonny Greenwood’s score, which has a way of accenting the characters, implanting them with an urgent undercurrent.

However unlikely it may seem at this point, the film also contains a lot of humor and romance. The hard-won conclusion is achieved in an unpredictable turn, revealing another nod to Psycho‘s Norman Bates, except oddly tender. Reynolds is a man haunted by the memory of his mother and, in a stroke of Freudian logic, may harbor an Oedipal fixation. In an early scene, before Alma invades their home, he admits to Cyril that their late mother has dominated his dreams. “I have an unsettled feeling based on nothing I can put my finger on,” he says. Reynolds continues to be a mama’s boy, a supremely talented man-child devoted to his mother’s ideal. (Note how, when he speaks of his childhood nanny, he calls the woman ugly and attacks her appearance. We cannot help but assume Reynolds’ nanny was the disciplinarian who refused to satiate the boy’s every wish, while his mother coddled him.) As a result, he does not want love from a romantic suitor. And so, the lengths to which Alma goes to finally capture Reynolds’ heart has a morbid, psychosexual edge with implications that reach far beyond what the film shows. In these cases, what is not shown is even more compelling than the full story denied to us. This is not to suggest that Phantom Thread is in any way incomplete or wanting; just that when an undeniably romantic, contented feeling occurs as these two find their rhythm, Anderson gives us only a brief, curious taste.

While Anderson borrows several strains from classic Hollywood, including the above-referenced Hitchcock nods and grandiose acting styles, the richness of his formal aesthetic is something else altogether. Serving as his own cinematographer, the director shoots his chamber drama in cramped spaces, where every footstep on the wooden floorboard is pronounced, and the scraping of butter on toast is “as if you rode a horse across the room.” Shooting on grainy 35mm, which has an incomparable, tactile appearance, Anderson uses soft, mostly natural light. His attention to detail reflects that of Reynolds, as he immerses the viewer in luscious sensory notes. Working in a visual style that he’s carried on both The Master and Inherent Vice (2014), he fills the frame with his characters’ pained and layered expressions during intimate scenes. At other times, in particular with scenes involving more than the three main characters or, later on, during a lively New Year’s Eve celebration, his camerawork echoes that of Max Ophüls, roving about the scene in unbroken shots that never draw attention to their considerable length. On formal terms, few modern filmmakers can match Anderson’s combination of assuredness and purpose.

While Anderson borrows several strains from classic Hollywood, including the above-referenced Hitchcock nods and grandiose acting styles, the richness of his formal aesthetic is something else altogether. Serving as his own cinematographer, the director shoots his chamber drama in cramped spaces, where every footstep on the wooden floorboard is pronounced, and the scraping of butter on toast is “as if you rode a horse across the room.” Shooting on grainy 35mm, which has an incomparable, tactile appearance, Anderson uses soft, mostly natural light. His attention to detail reflects that of Reynolds, as he immerses the viewer in luscious sensory notes. Working in a visual style that he’s carried on both The Master and Inherent Vice (2014), he fills the frame with his characters’ pained and layered expressions during intimate scenes. At other times, in particular with scenes involving more than the three main characters or, later on, during a lively New Year’s Eve celebration, his camerawork echoes that of Max Ophüls, roving about the scene in unbroken shots that never draw attention to their considerable length. On formal terms, few modern filmmakers can match Anderson’s combination of assuredness and purpose.

Returning to the dresses that began this review, Phantom Thread contains a surface level beauty that will excite fashion enthusiasts (knowing nothing about such things, this critic was still enthralled). Costume designer Mark Bridges has made gowns worthy of James and Balenciaga, while production designer Mark Tildesley creates interiors that look lived-in but no less extravagant. The brilliant performances are just as intricate and considered. Anderson’s filmmaking is exquisite and sumptuous, even as the ending will no doubt bewilder those who find Anderson’s characters and narrative structure too thorny, too impenetrable, or too unconventional. And yet, Phantom Thread has more feeling and emotional range in its restrained drama than some of his other works—this is certainly the most raw emotion he’s produced since Punch Drunk Love (2002). But requiring the viewer to mine for and decipher hidden emotions makes appreciating his distinctive brand of filmmaking all the more satisfying. The rewards will keep revealing themselves in future viewings to be sure, where the film will continue to grow—the sign of any lasting, essential work of cinema.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review