Personal Shopper

By Brian Eggert |

Enigmatic and haunting, Olivier Assayas’ Personal Shopper tells a kind of ghost story, though the title suggests anything but, as does the resulting picture. Several scenes take place in a spooky old house, the poorly lit sort with wooden floors that creak with every step; ethereal figures float, spewing ectoplasm and alluding to an ominous secret; a gruesome murder sends chills up the spine; and a playful game of cat-and-mouse via text turns frightening. Regardless of such tropes from an otherwise conventional thriller, Assayas incorporates them, along with a rather brilliant and engaging structure, into a puzzling drama whose emotional resonance pulls the viewer through several stages of misdirection. With an elusive spiritualism that reflects the nature of the drama, Personal Shopper will not offer definite answers, although its clues remain fulfilling enough for audiences that need not be catered to.

A former critic for the famed Cahiers du cinéma, Assayas has been directing since the late 1980s. Ever film-savvy, he often defies our expectations of genres and blends them in fascinating, unexpected ways. His films never end up where they initially seem to be going. For instance, his 1996 breakout Irma Vep followed a filmmaker (none other than Jean-Pierre Léaud) trying to complete a Hong Kong-styled remake of the silent crime serial Les vampires within the broken French film industry of the time. Perhaps it’s needless to say that Assayas’ multilayered and unpredictable approach does not speak to the majority of most western moviegoers who, generally speaking, are adverse to the mental work required to penetrate an Assayas viewing experience. Relegated to arthouses where his beautiful films remain underseen, Assayas has developed into the cerebral director of Summer Hours (2008) and the epic miniseries Carlos (2010). His most recent film, The Clouds of Sils Maria (2014), marked his first collaboration with Kristen Stewart.

Playing an assistant opposite Juliette Binoche’s actress-employer in that film, Stewart demonstrated an artistic prowess and command of her talents that almost completely buried any lingering associations with vampires or werewolves. (After all, Stewart held her own with Binoche, which is saying something.) The performance earned Stewart a César, France’s equivalent to an Oscar, marking the first time an American performer had won for Best Supporting Actress. She has gravitated toward independent productions in recent years, avoiding the usual blockbusters (she passed on a sequel to her Snow White and the Huntsman) in favor of titles like Camp X-Ray and Certain Women. She might be the best young actress working today. And if The Clouds of Sils Maria was the beginning of an ongoing collaboration between Assayas and Stewart, then Personal Shopper presents a more internalized, albeit superior outcome.

Stewart plays Maureen, an assistant to Kyra (Nora von Waldstatten), a tabloid diva located in Paris. Maureen runs errands for the helpless celeb, everything from updating Kyra’s laptop to hand-selecting pieces of haute couture from Paris’ top designers for Kyra to wear. Most people would kill for a job driving around the City of Lights and shopping with someone else’s money, but Maureen has been barred from ever trying on Kyra’s clothes. Worse, Kyra remains an insufferable prima donna, putting Maureen in an awkward position when she refuses to return the designer clothes she’s rented for a night. Maureen only endures her thankless career because her stay in Paris is temporary. “I’m waiting,” she explains. You see, her brother died a couple of months earlier. In addition to being twins, Maureen and her brother, Lewis, shared the heart defect that killed him and the ability to sense the supernatural.

Stewart plays Maureen, an assistant to Kyra (Nora von Waldstatten), a tabloid diva located in Paris. Maureen runs errands for the helpless celeb, everything from updating Kyra’s laptop to hand-selecting pieces of haute couture from Paris’ top designers for Kyra to wear. Most people would kill for a job driving around the City of Lights and shopping with someone else’s money, but Maureen has been barred from ever trying on Kyra’s clothes. Worse, Kyra remains an insufferable prima donna, putting Maureen in an awkward position when she refuses to return the designer clothes she’s rented for a night. Maureen only endures her thankless career because her stay in Paris is temporary. “I’m waiting,” she explains. You see, her brother died a couple of months earlier. In addition to being twins, Maureen and her brother, Lewis, shared the heart defect that killed him and the ability to sense the supernatural.

A self-described medium, Maureen does not conduct séances or read palms; she’s not even sure if she believes in the afterlife. She’s capable of sensing vague, otherworldly presences. As for Paris, Maureen and Lewis made a pact: whoever departs first, the surviving sibling would wait around the area where the death occurred for a sign from the other. And so, Maureen spends nights alone at the French estate where he used to live, hoping for a sign that proves the existence of the afterlife, and what’s more, proves Lewis is at peace. Meanwhile, she despises Kyra and never sees her boyfriend, who’s working overseas in Oman. She seems caught in multiple states of limbo at once—between her role as a personal shopper and the rest of her life, between her former life and a new one, between life and death. Her unsettled state breeds restlessness that Stewart portrays through her character’s perpetual disorientation and unease, and her declining inhibitions.

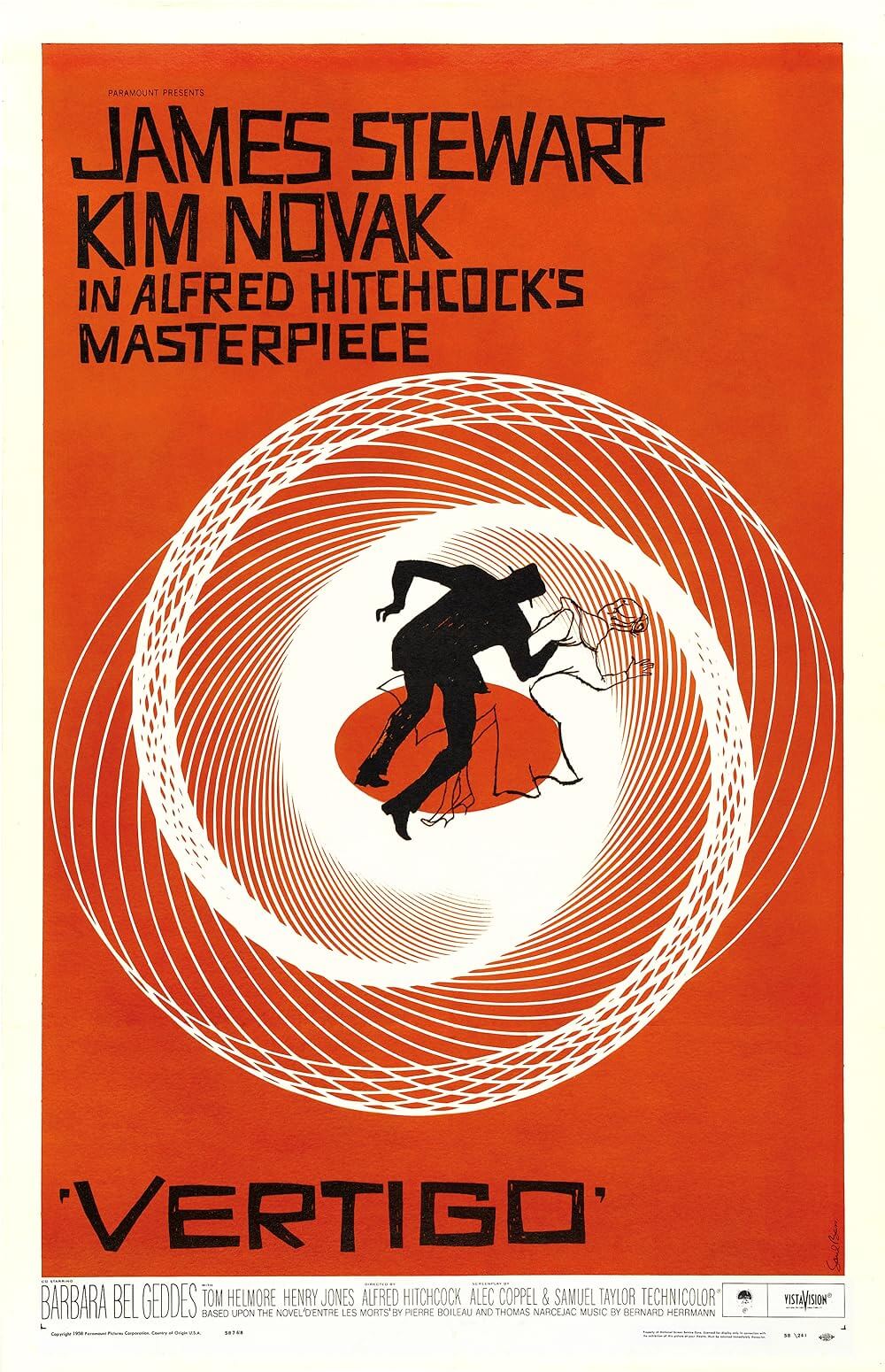

It begins with mysterious texts. An unknown sender contacts Maureen and asks questions, some vaguely coquettish, some almost threatening. Could it be Lewis? Maureen has just discovered the works of Swedish artist Hilma af Klint, a painter whose abstractionist style seems to predate the abstract movement, an oddity perhaps explained by how af Klint communed with the spirits of the dead (Maureen learns French novelist Victor Hugo did the same). Does this mean something? Assayas had Stewart texting a lot in The Clouds of Sils Maria too, but somehow he makes the progression of blips and notifications urgently watchable. The increasingly voyeuristic texts compel Maureen to admit that she wants to try on Kyra’s stylish dresses, a forbidden act which nonetheless she carries out, because, as Ovid wrote, “We are ever striving after what is forbidden, and coveting what is denied us.” This leads to Maureen pleasuring herself on her employer’s bed, in her employer’s clothes, in a scene both erotic and suspenseful—evoking an unmistakably Hitchcockian balance. Later, that same bedroom is the site of a murder.

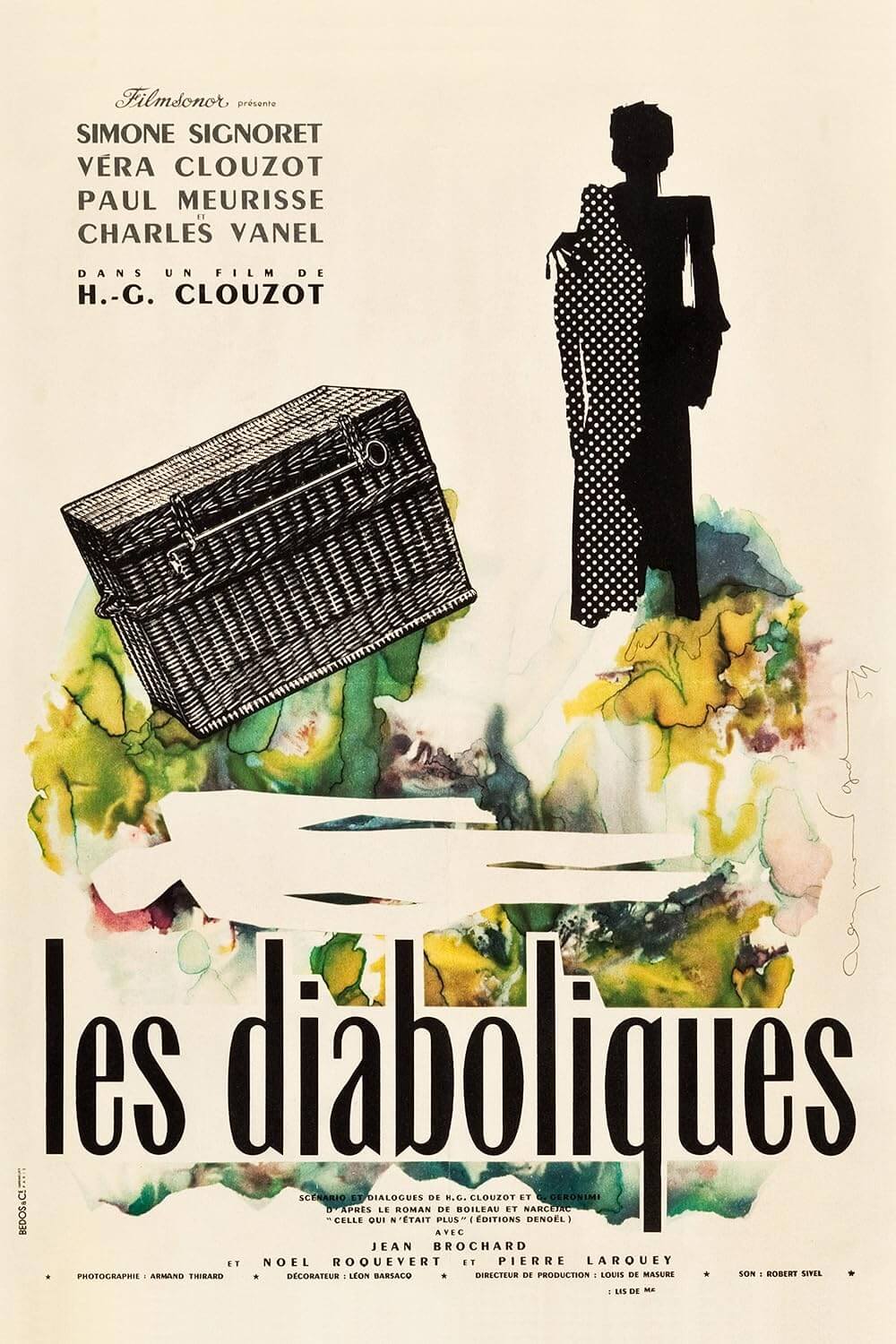

If Vertigo (1958) comes to mind, and it should, then so must Diabolique (1955), the French thriller by Henri-George Clouzot, based on a novel by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, the same authors as Hitchcock’s tale of obsession. In Clouzot’s masterpiece, the vulnerable protagonist worries that a ghost haunts her, while the viewer remembers perhaps better than she does about her fragile heart condition—just as we do for Maureen. Undoubtedly, Assayas hoped to channel Boileau and Narcejac with Personal Shopper; however, the writer-director summons his own style in the way he observes Maureen. Assayas is not known for formal bravado; his visual style is lyrical, natural, and deceptively recessive. His cinematographer Yorick Le Saux (I Am Love, Only Lovers Left Alive) hangs back, watching Maureen from a distance, trying to grasp her in the same way she’s trying to get ahold of her life. All the while, Steward is magnetic; she’s onscreen for virtually every frame, bringing her character to life by inhabiting her character’s sense of loss, self-enforced detachment, and lingering sorrow.

If Vertigo (1958) comes to mind, and it should, then so must Diabolique (1955), the French thriller by Henri-George Clouzot, based on a novel by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, the same authors as Hitchcock’s tale of obsession. In Clouzot’s masterpiece, the vulnerable protagonist worries that a ghost haunts her, while the viewer remembers perhaps better than she does about her fragile heart condition—just as we do for Maureen. Undoubtedly, Assayas hoped to channel Boileau and Narcejac with Personal Shopper; however, the writer-director summons his own style in the way he observes Maureen. Assayas is not known for formal bravado; his visual style is lyrical, natural, and deceptively recessive. His cinematographer Yorick Le Saux (I Am Love, Only Lovers Left Alive) hangs back, watching Maureen from a distance, trying to grasp her in the same way she’s trying to get ahold of her life. All the while, Steward is magnetic; she’s onscreen for virtually every frame, bringing her character to life by inhabiting her character’s sense of loss, self-enforced detachment, and lingering sorrow.

Even though Assayas went on to win the Best Director prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 2016, Personal Shopper’s uncertain ending earned boos. Some audiences can’t stand ambiguity. To be sure, Assayas does not resort to a tidy finish as Hitchcock would have; several sequences contain an intangible meaning that will require the viewer to interpret. Films with an imprecise ending can disappoint if, earlier on, deficient storytelling does not allow the audience to project substantial answers on an opaque conclusion. But Personal Shopper is not one of those films. Whatever decisions the viewer makes about the plot, the film resonates as a study of grief and a search for answers, guided by Stewart’s intricate and moving performance. Just as in The Clouds of Sils Maria, in which Stewart disappeared from the screen, Assayas and his perfomer create an evocative work that defies classification and urges further examination.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review