Persepolis

By Brian Eggert |

The Islamic revolution in Iran—what an atypical setting for a graphic novel-to-film adaptation. But Persepolis, Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical account of growing up in such an environment, is about cultural identity, how we often deny it, even though it dwells within us for our whole lives. She calls it a movie with universal appeal, despite delving deep into Iranian politics because we all search for freedom and independence from our backgrounds. Following benchmark graphic novels like Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Joe Sacco’s Palestine, Satrapi’s prose faces the question of cultural identity amid horrifying political circumstances. Maus deals with the Holocaust; Palestine centers on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Satrapi’s two-volume work was published in France in 2000 and in the U.S. in 2003, and it remains comparatively light and even melodramatic in comparison. Not that the setting is any less significant; the revolution is one of the most significant in world history.

Iran was under the foot of monarch Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi until 1978 when the first demonstrations began to push the Shah out and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in. West-funded weapons pushed the revolts forward, with the promise of oil in return. Iran was to become the Islamic Republic, but the result was another form of oppression under an alternate figurehead. The fear of walking down the street subsided only temporarily. Satrapi’s narrative tells of her childhood, growing up as a young girl and witnessing things no child should have to contemplate. Fundamentals changed, and women were forced to hide behind scarves and are openly considered the minority in an ideological segregation of sexes. In one scene, Marjane’s mother warns her of the world with tears rolling down her face, telling her of a woman who authorities had it out for; the woman is a virgin, and since there are religious implications for killing a virgin, a guard married her, raped her, and then was free to hang her.

But little Marjane is a blithe force with rebellion in her blood. Her parents and grandmother are also unsympathetic to monarchical regimes, remaining suspect of any government with too much power. At a young age, educated in French-speaking schools in Tehran, Marjane finds her method of rebellion in Iron Maiden death metal sold on the black market. Her hot temper instigates a few snaps at police, who raid boy-girl parties hunting for liquor and unofficial music. She moves to Vienna to avoid being swallowed up by the new equally oppressive government, becomes a woman, learns some life lessons, and falls in love (repeatedly, and disastrously). Being Iranian, she finds, never goes away, no matter how hard she tries, no matter how many people she tells that she’s French. Her endearing grandmother tells her to be true to herself. But even as she accepts her cultural origins, going home and being herself is nearly impossible with the repressive scenery of the “reformed” Iran.

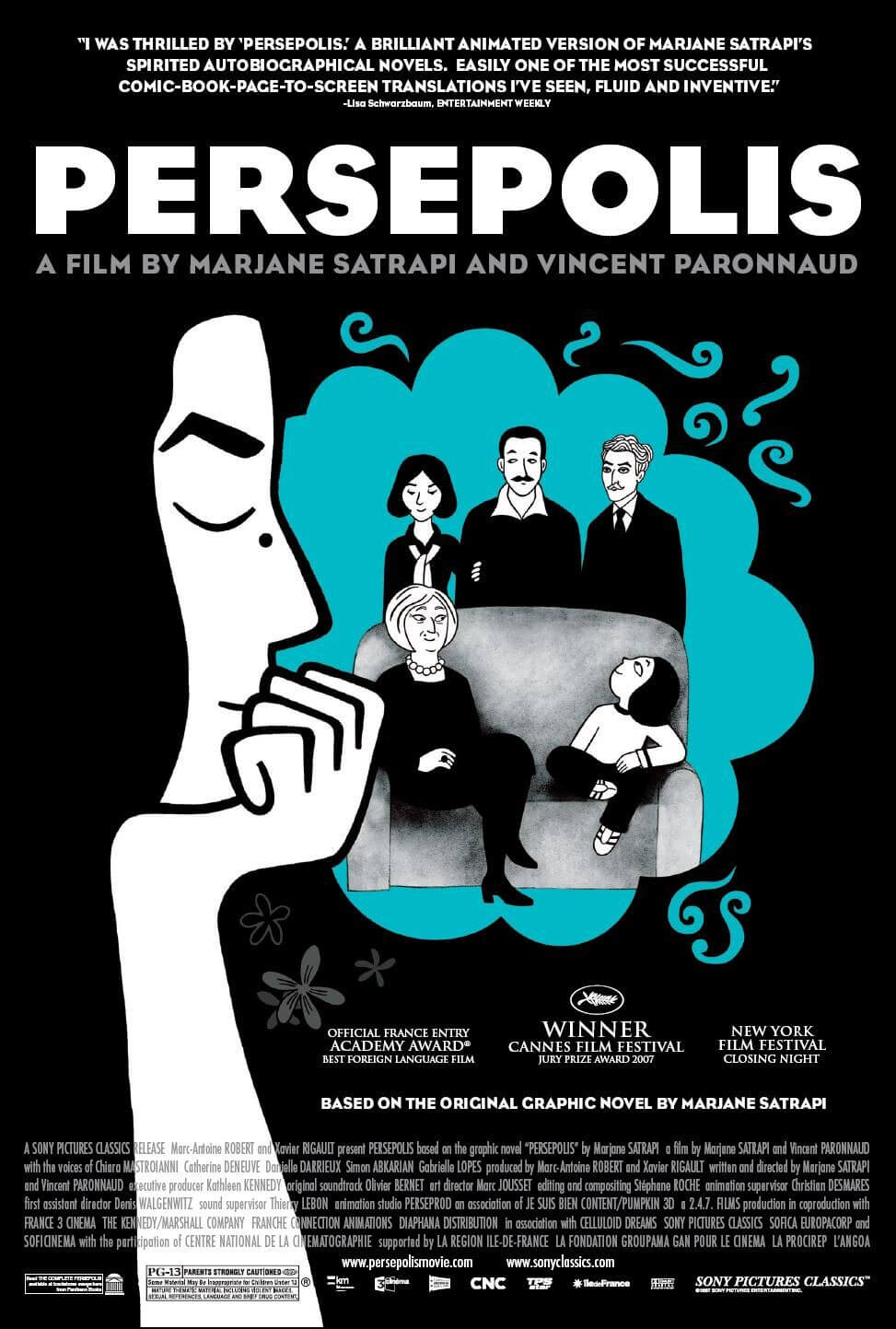

Satrapi didn’t always want her story told in cinematic form. Her reluctance was eased by producer Marc-Antoine Robert, who offered to film the picture in France, allowing Satrapi to animate it in black and white, staying accurate to her vision. The film is animated in black and white, with bookend color sequences denoting the present day. Some might compare the style to The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine, in that flat, heavily outlined figures sometimes move rigidly, and, other times, flow, gesticulating like bags of water. Backgrounds are given a sketch-like detail, realistic or surreal, depending on the scene’s requirements. It’s a cartoon when it needs to be, and a graphic realization when it needs to be. The animation mode fits the mood of Satrapi’s characters, fulfilling a promise that Satrapi herself calls superior to the print source. Kathleen Kennedy, the mogul producer usually associated with Tom Cruise, offered to buy the rights for an American production, but Satrapi refused; instead, Kennedy donned the production with money and assured a more popularized, worldwide release.

Vincent Paronnaud, co-director, complimented Satrapi’s comic-book page in the way Robert Rodriguez fleshed out Sin City with Frank Miller’s help. Except, Satrapi insisted on creative approval of every decision. She even coached the voice actors and instructed the animators on the living version of her graphic novel’s art. She told The New York Times that on set, she referred to her character in the third person to put distance between “Marjane the Filmmaker” and “Marjane the Subject of Persepolis.” Whenever she thought about her grandmother, now dead, she would burst into tears, thinking about how this cartoon was bringing her family back to life. Indeed, these otherwise two-dimensional characters carry affecting substance, involving us in an entertaining story of family and identity, told with fantastic visuals and heartening characters. It’s another important elevation of animation from children’s entertainment to pronounced, artistic cinema.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review