Reader's Choice

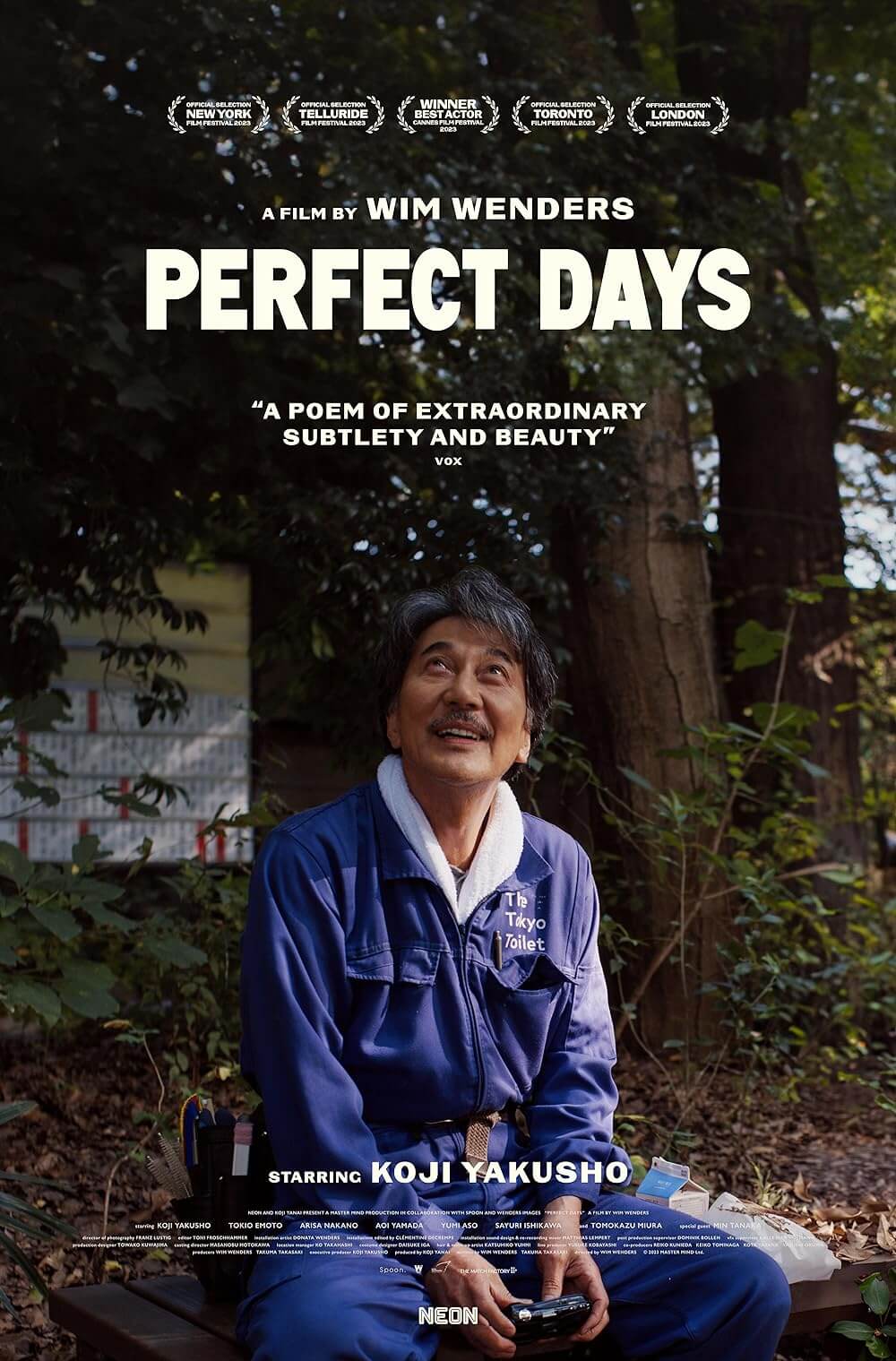

Perfect Days

By Brian Eggert |

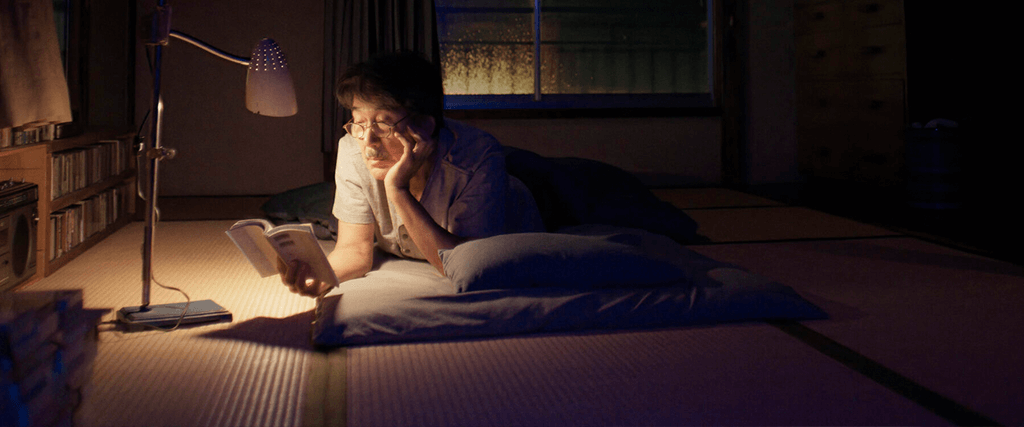

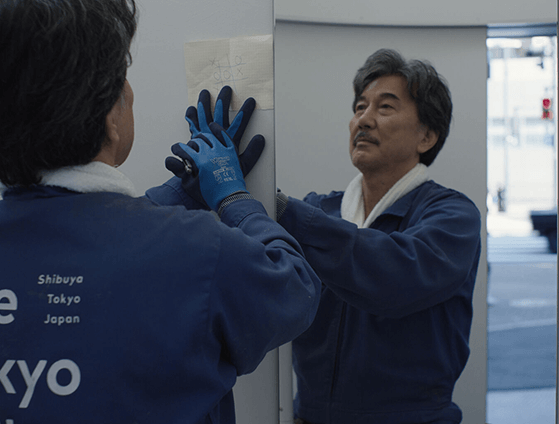

Delicate and meditative, Wim Wenders’ Perfect Days adopts a wabi-sabi outlook that welcomes the cycles of life and finds beauty in imperfect situations. Koji Yakusho gives a marvelous performance as Hirayama, a middle-aged man who works for The Tokyo Toilet, a high-end restroom service in Japan’s capital city. Immersed in Hirayama’s routines and the deviations that upset them, the film observes him waking up each morning to the sound of a neighbor sweeping the street. Hirayama brushes his teeth, waters his plants, readies his blue jumpsuit, looks up at the sky with a smile, and then, on his drive to work, he listens to The Velvet Underground, Patti Smith, The Kinks, or Nina Simone on cassette (the soundtrack is uniformly excellent). Between scrubbing toilets and wiping down surfaces, he stops for lunch in a park and, using a ‘90s-era camera, takes photos of the sun peering through trees, which casts hypnotic shadows. After work, he visits a public bathhouse and gets a bite to eat. Then, it’s home to read a few more pages of his latest book before bed. And that’s about it. But in true Wenders form, by the end, after having been with Hirayama for several days, we feel like we’ve taken a long journey and come out wiser for the experience.

Perfect Days is a welcome return for the German-born but worldly director. At one point in his career, Wenders was a maverick filmmaker whose cutting-edge European aesthetics blended with the decidedly American theme of searching for oneself on the open road, crafting an altogether new voice. After his German-language Road Trilogy—Alice in the Cities (1974), The Wrong Move (1975), and Kings of the Road (1976)—earned him accolades in the New German Cinema movement, he began working in Hollywood and helped define the arthouse movement of the 1980s with Paris, Texas (1984) and Wings of Desire (1987). But his work in the subsequent decades has been inconsistent and floundering, ranging from the pulp nonsense of Million Dollar Hotel (2000) to Everything Will Be Fine (2015), the best-left-forgotten James Franco drama shot in 3D. Perfect Days marks Wenders’ first essential narrative feature in over three decades, since 1991’s Until the End of the World. It has the austerity and visual poetry of Wenders’ best work, and its narrative simplicity is overwhelmingly entrancing.

At the same time, it’s worth considering whether Perfect Days is an extended commercial for The Tokyo Toilet, a real-life company with luxury restrooms located around Shibuya, a special ward in Tokyo. With 17 locations, each from a unique designer, the toilets are a product of Japan’s rich sense of hospitality. According to the company’s website, regular cleanings play a significant role in sustaining the experience, so there’s someone actually carrying out Hirayama’s daily rounds in real life. Regardless, most humans know that public restrooms are the worst; if they’re not covered in lewd graffiti, they’re covered in various bodily fluids or substances. Perhaps it’s good marketing on The Tokyo Toilet’s part that Hirayama never finds one of the toilets left in a disgusting state by some inconsiderate user. There’s never a moment equal to Trainspotting’s (1996) “worst toilet in Scotland” scene or anything even approaching that. While it may be somewhat unrealistic not to acknowledge the occasional vile disaster, it’s also an intelligent promotional device.

In any case, Wenders co-scripted the film with Japanese screenwriter Takuma Takasaki, and the result recalls Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson (2016), featuring Adam Driver as an inward man who, when he’s not driving a city bus, enjoys quietly observing Nature and writing poetry. But the minimalist Paterson feels narratively dense next to Perfect Days, whose gentle rhythms consume Hirayama’s time. The protagonist barely talks, despite his endlessly jabbering coworker, Takashi (Tokio Emoto). Hirayama describes him as “a great worker, but not a great speaker.” It’s not that Hirayama can’t speak; he just has nothing to say in most situations. Content in the control of his disciplined life, he receives everything with simplicity, undisturbed by the thoughtlessness, sloppiness, and mess of people. Even after Takashi interrupts Hirayama’s schedule to bum a ride for a failed date with Aya (Aoi Yamada), he only balks to prevent Takashi from pawning his vintage tapes for cash. It’s enough that he can do his job well, look up at the trees or Tokyo’s sparkling Skytree, and appreciate their beauty. Not even a rainy day can bring him down.

In any case, Wenders co-scripted the film with Japanese screenwriter Takuma Takasaki, and the result recalls Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson (2016), featuring Adam Driver as an inward man who, when he’s not driving a city bus, enjoys quietly observing Nature and writing poetry. But the minimalist Paterson feels narratively dense next to Perfect Days, whose gentle rhythms consume Hirayama’s time. The protagonist barely talks, despite his endlessly jabbering coworker, Takashi (Tokio Emoto). Hirayama describes him as “a great worker, but not a great speaker.” It’s not that Hirayama can’t speak; he just has nothing to say in most situations. Content in the control of his disciplined life, he receives everything with simplicity, undisturbed by the thoughtlessness, sloppiness, and mess of people. Even after Takashi interrupts Hirayama’s schedule to bum a ride for a failed date with Aya (Aoi Yamada), he only balks to prevent Takashi from pawning his vintage tapes for cash. It’s enough that he can do his job well, look up at the trees or Tokyo’s sparkling Skytree, and appreciate their beauty. Not even a rainy day can bring him down.

Wenders and cinematographer Franz Lustig capture Hirayama’s clockwork schedule in scenes that underline how, though his days may be similar, he doesn’t feel bogged down by their repetition. Visually, the filmmakers never suggest the routine is dull or stifling by employing the same shots over and over; rather, the variety of angles and perspectives suggest that Hirayama treats every day as something new. His dreams further break the visual patterns, with impressionistic black-and-white imagery faintly recalling events from Hirayama’s day and hinting at which aspects linger in his subconscious. However, the production’s boxy Academy aspect ratio acknowledges that the protagonist has actively limited his world—a more evident theme in the second half. But until then, Wenders and editor Toni Froschhammer establish a flow, with familiar characters appearing daily. Hirayama spies a homeless man (Min Tanaka) in a park and, on weekends, visits a restaurant where the resident chef (Sayuri Ishikawa) offers hints of a budding romance. The older gentlemen at the public baths or the strange woman who stares at him in the park become familiar faces as well.

Wenders has such confidence in his mesmerizingly simple presentation that, throughout several revolutions in Hirayama’s routine, a game of tic-tac-toe played on a scrap of paper hidden in one of the bathrooms conjures a light suspense. It might even be regretful that his niece, Niko (Arisa Nakano), shows up to change his habits, requiring him to bring her along on his shifts. They form a lovely bond, both having clashed with Niko’s mother for reasons that go unexplained—though, when Niko says she identifies with the boy from Patricia Highsmith’s short story “The Terrapin,” who stabs his mother to death, that tells us everything we need to know. In his eventual meeting with his sister (Yumi Asō), the film hints that Hirayama’s lifestyle is a mask disguising a deep pain and sadness, and Wenders recognizes that pain without over-explaining it. The subtle acknowledgment is enough to reveal Hirayama’s wounded reality as a kind of therapy in the face of significant trauma, if not also an escape from the rat race. The final extended shot featuring Yakusho alternating between profound sadness and joy becomes an outpouring of a performance that has brilliantly concealed these feelings.

Fittingly, Yakusho earned the Best Actor award at the Cannes Film Festival earlier this year, and his beguiling performance remains among the year’s best. For much of the film, the actor inhabits a dialogue-free space, requiring him to evoke through microscopic gestures a personality that needs to see the world’s good side. Wenders’ music choices throughout Perfect Days can sometimes feel on-the-nose, such as The Animals’ cover of “The House of the Rising Sun” for a film set in the so-called Land of the Rising Sun—a Western term for Japan. Of course, Lou Reed’s oft-used “Perfect Day” also finds its way into the mix. But if these arguably overplayed songs have been frequently deployed in cinema, they’re no less effective here in Hirayama’s soundtrack to his life. Giving way to heartrending emotions, Perfect Days is a modest yet resounding triumph. Wenders finds poetry in the everyday while acknowledging that, even behind the outwardly mundane or most menial of jobs, people still ache with humanity.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on December 6, 2023.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review