Reader's Choice

Perfect Blue

By Brian Eggert |

A psychological thriller that explores the byproducts of obsessive fandom, director Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue, his feature-length anime debut, features a synthesis of the internal and external, the private and public, the real and fantastic. Based on the novel by Yoshikazu Takeuchi, the film considers how pop culture and technology supply an escape from the confines of the real world and thus considers their potential dangers. Although the story could have easily been adapted into a live-action feature, Kon’s treatment nonetheless establishes preoccupations evident throughout his career, first as a manga artist and writer, then a screenwriter and storyboard artist, and then an anime feature filmmaker. Reality, pop fabrication, cyberspace, and hallucinations form an indistinguishable whole at first, and only as the film carries on do the fissures between them reveal the cracked psyches at their center. Given its structure, Perfect Blue opens itself to comparative analysis and psychoanalytic interpretation. However, it’s far more interesting as a critique of media culture and its effect on both the audience and talent involved. Even if these thematic preoccupations inspire, the characters remain at a remove, leaving the red herrings and climactic twists underdeveloped. Still, it’s not a film that’s easily shakable.

Set in Japan’s pop idol industry, Perfect Blue reveals an entire network of talent exploitation, marketing, and consumption. The story follows Mima Kirigoe, the most talented member of a modestly successful J-pop trio called CHAM!, in which she appears dollish and childlike. Though she aspires to break away from her teen idol persona and become a mature actress, Mima’s public image transformation is constantly informed by those who shape and react to her: her agent Tadokoro; her manager Rumi, a former pop idol herself; her enthusiastic fanbase; her stalker, Mamoru Uchida, a Mi-Maniac with bad teeth and eyes so far apart that he looks almost alien; and the bloggers who write about her life. In the process of manufacturing her new, sexy image, Mima sets aside her kawaii-infused CHAM! identity for a provocative photoshoot and a small role on Double Bind, a television series. Her manager negotiates a larger role on the show, but the expansion includes a traumatic rape scene. Mima believes that if Jodie Foster could legitimize herself with an Oscar for The Accused (1988), a film with a brutal gang rape scene, so can she.

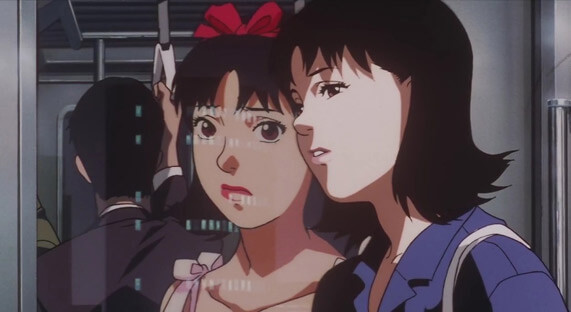

Early in the film, Kon introduces the prominent motif of the inward and outward, represented through a series of reflective doubles and contrasts between the figurative and literal inside and outside. Mima takes the train home from a CHAM! concert and looks out the window, peering as if through a computer or television screen at the world outside. There’s an invisible pane of glass between herself and the real world, and sometimes that separator returns the image of her stage persona. Indeed, the relationship between Mima’s private self and her external identity informs not only the visual texture of Perfect Blue but how Kon regularly intercuts between Mima’s scenes in her apartment with her various types of performance—some on-stage with CHAM!, some in front of the camera for Double Bind. Inside, alone in her apartment, she maintains a tenuous connection to her family with the occasional telephone call, but her performative self regularly invades her thoughts. While alone, she also reads first-person entries on the website called “Mima’s Room,” which claims to be Mima’s actual diary and includes frighteningly accurate and up-to-date entries about Mima’s inner thoughts. Mima is flattered at first, and then she’s disturbed. The viewer begins to wonder whether a fan authored the website, or if she has developed a multiple personality disorder and wrote them without knowing.

Early in the film, Kon introduces the prominent motif of the inward and outward, represented through a series of reflective doubles and contrasts between the figurative and literal inside and outside. Mima takes the train home from a CHAM! concert and looks out the window, peering as if through a computer or television screen at the world outside. There’s an invisible pane of glass between herself and the real world, and sometimes that separator returns the image of her stage persona. Indeed, the relationship between Mima’s private self and her external identity informs not only the visual texture of Perfect Blue but how Kon regularly intercuts between Mima’s scenes in her apartment with her various types of performance—some on-stage with CHAM!, some in front of the camera for Double Bind. Inside, alone in her apartment, she maintains a tenuous connection to her family with the occasional telephone call, but her performative self regularly invades her thoughts. While alone, she also reads first-person entries on the website called “Mima’s Room,” which claims to be Mima’s actual diary and includes frighteningly accurate and up-to-date entries about Mima’s inner thoughts. Mima is flattered at first, and then she’s disturbed. The viewer begins to wonder whether a fan authored the website, or if she has developed a multiple personality disorder and wrote them without knowing.

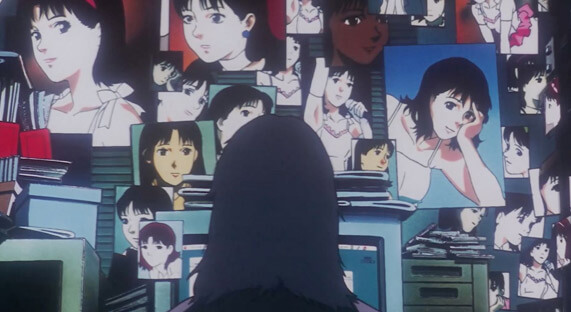

As Mima submits to the desires and needs of others in place of her own, in a sense killing her former self, she succumbs to hallucinations. She begins to see her former pop-idol persona as a sprightly, disembodied entity who attempts to supplant the real Mima with the pixielike alternative, sabotaging her career in more mature output to join her pop trio once again. When Mima’s staff, who regularly treat her like a child, receives an exploding letter, the viewer cannot help but wonder if she sent it. After her photographer and Double Bind’s writer end up brutally stabbed to death, Mima begins to believe the culprit may be her stalker or worse; she may be responsible, acting out as her CHAM! persona. Uchida, the author of “Mima’s Room,” suggests Mima is an impostor, and the real Mima is her pop identity. The motif becomes palpable when she receives a fax with the word “traitor” scrawled across the page, and then Kon suddenly cuts to Mima’s performance in Double Bind, in which she asks, “Who are you?”

Kon’s intercutting blurs our ability to distinguish between reality, performance, and hallucination, and throughout, the question “Who are you?” is repeated like a refrain. The question can be read as a query into both the stalker’s and Mima’s identities. That the identities in the film become so fractured is even more tragic given their lowbrow cultural status. Mima never achieves superstardom. Her former J-pop group seems overjoyed to be listed in the eighties on the pop charts, and her screen debut involves a thankless guest spot on a television show. Mima’s definition of adulthood and serious acting involves a deeply exploitative and disturbing sequence that, once performed, has a real traumatic consequence that is mirrored when Uchida attempts to rape her in reality, reenacting the scene filmed for Double Bind. The lowbrow milieu cannot help but recall the air of B-movie cheese prevalent in Brian De Palma’s Blow Out (1981), another film that blends murderous performance and reality in disturbing ways. But where De Palma unabashedly delights in exploitation, Kon’s censure of the patriarchal entertainment industry falls into an ideological trap.

Most assessments of Perfect Blue reference Kon’s influence on American filmmaker Darren Aronofsky, who lifts visual and thematic touches for his films Requiem for a Dream (2000) and Black Swan (2010). However, Kon’s work proves far more layered, inspired, and less referential than Aronofsky’s style-over-substance approach, in which his allusionism is often overlooked. And besides, Kon’s film is not without stylistic antecedents. Perfect Blue superficially resembles a classic De Palma-style setup, such as Dressed to Kill (1980) or Body Double (1984), wherein fractured minds create alternate identities and lash out, often using a phallic weapon, while the director observes from a distinctly masculine perspective. By extension, Perfect Blue earns its many comparisons to Italian Giallo, which also follows crazed killers with personality disorders and a generally exploitative eye. The violent deaths in Perfect Blue, in familiar locales such as an elevator, cannot help but recall earlier slashers, and the killer’s sexual and existential motivation for stabbing out eyes brings to mind Francis Dolarhyde in Red Dragon.

Most assessments of Perfect Blue reference Kon’s influence on American filmmaker Darren Aronofsky, who lifts visual and thematic touches for his films Requiem for a Dream (2000) and Black Swan (2010). However, Kon’s work proves far more layered, inspired, and less referential than Aronofsky’s style-over-substance approach, in which his allusionism is often overlooked. And besides, Kon’s film is not without stylistic antecedents. Perfect Blue superficially resembles a classic De Palma-style setup, such as Dressed to Kill (1980) or Body Double (1984), wherein fractured minds create alternate identities and lash out, often using a phallic weapon, while the director observes from a distinctly masculine perspective. By extension, Perfect Blue earns its many comparisons to Italian Giallo, which also follows crazed killers with personality disorders and a generally exploitative eye. The violent deaths in Perfect Blue, in familiar locales such as an elevator, cannot help but recall earlier slashers, and the killer’s sexual and existential motivation for stabbing out eyes brings to mind Francis Dolarhyde in Red Dragon.

Of course, one cannot ignore the male orientation of Kon’s visual treatment in Perfect Blue. Even as he critiques how Mima is objectified and infantilized by those around her, Kon takes part in her objectification by cutting in abrupt, fragmentary images of Mima’s breasts and pubic hair in the mix. It’s a characteristic of Perfect Blue and entire subgenres of anime, including comic high-school romances, body horror, mecha, Hentai, and others, which create a set of representational contradictions about identity and female agency. And yet, Kon’s films often feature female protagonists, but none have been so sexualized as Mima. He told the Washington Post, “As I am a man, if I should decide to have a young man as the central figure in the movie, then I would know that young man too well. Having a different gender person as the main character, I personally want to know more about that main character.” Kon owns up to his interest in Mima, an interest that extends beyond her identity crisis and into a sexual fascination from a male point of view. His film’s paranoia about being watched supplies a worthy condemnation of these male-dominated modes of looking and exploitation. Still, it falls into a familiar paradox of representation that perpetuates the very thing it seeks to expose.

The ending of Perfect Blue reveals what happens when a pop-culture image takes over an entertainer’s identity completely, leaving them, as Japanese scholar William O. Gardner observed, “unable to resolve the tension between establishing their own subjectivity and serving as the object of the male gaze.” As it turns out, Rumi, Mima’s agent, has adopted Mima’s pop idol identity as a second personality and killed to preserve it—a transformation so complete that it convinces Uchida. In her final confrontation with Mima, Rumi, pierced by shards of mirror no less, dies in a CHAM! costume. The film’s explanatory ending, reminiscent of the scenes in Psycho (1960) that diagnose Norman Bates, reveals Rumi as a victim of dissociative identity disorder. She serves as a warning of where obsessing over one’s public image could land Mima: middle-aged, bloated, and clinging to her former celebrity with violent intensity. Still, Mima’s self-doubt about which version of herself is real or imagined lingers, leaving the viewer wondering whether Mima will end up like Rumi—a fractured mind locked away at a mental hospital.

Much of Kon’s other work concentrates on how the mind processes media, cinema, and the internet above all. In his second feature, Millennium Actress (2001), the central character is an aging film star who reminisces about her career to an interviewer and cameraman. Her recollections prove so powerfully connected to her audience’s visual memory of iconic moments from Japanese film history that they are transported into a cinematic fantasy, seen through the eyes of her male spectator. At one moment, they are samurai in an Akira Kurosawa-inspired scene; the next moment, they have dropped inside of Godzilla (1954). Millennium Actress‘ appreciation of cinema’s transportive possibilities is sharply contrasted in Kon’s Paprika (2006), where film and dream imagery conspire with artificial spaces on the internet to influence the subconscious. A device called a “DC Mini” allows a therapist to enter the dreams of patients and work through their underlying hangups. But once invaded by a malignant outside influence, the device sends dreams spilling out into reality, confusing the two in a sublime array of intricately detailed visual information. The outlier among Kon’s features is Tokyo Godfathers (2003), a sentimental and Capra-esque comedy about three homeless people who find an abandoned baby on Christmas Eve and weigh whether to adopt the miracle child or find her parents.

Much of Kon’s other work concentrates on how the mind processes media, cinema, and the internet above all. In his second feature, Millennium Actress (2001), the central character is an aging film star who reminisces about her career to an interviewer and cameraman. Her recollections prove so powerfully connected to her audience’s visual memory of iconic moments from Japanese film history that they are transported into a cinematic fantasy, seen through the eyes of her male spectator. At one moment, they are samurai in an Akira Kurosawa-inspired scene; the next moment, they have dropped inside of Godzilla (1954). Millennium Actress‘ appreciation of cinema’s transportive possibilities is sharply contrasted in Kon’s Paprika (2006), where film and dream imagery conspire with artificial spaces on the internet to influence the subconscious. A device called a “DC Mini” allows a therapist to enter the dreams of patients and work through their underlying hangups. But once invaded by a malignant outside influence, the device sends dreams spilling out into reality, confusing the two in a sublime array of intricately detailed visual information. The outlier among Kon’s features is Tokyo Godfathers (2003), a sentimental and Capra-esque comedy about three homeless people who find an abandoned baby on Christmas Eve and weigh whether to adopt the miracle child or find her parents.

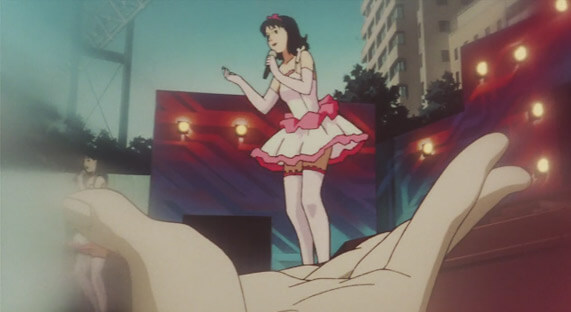

Unlike Kon’s later films, Perfect Blue’s animation rarely calls attention to itself, albeit artfully so. Note how the CHAM! crowds appear as a faceless mass in an image that might seem lazy if not for what it says about fandom. And the memorable moment when Uchida holds up his hand, so it appears as though Mima is dancing in his palm, is an iconic image rendered without over-stylized flair. Still, at 82 minutes, the story needs more room to breathe. Given the many twists and turns in the film’s final scene, the narrative explanation of possession by illusion doesn’t quite satisfy all the viewer’s questions. Furthermore, Mima’s choice to continue acting after this ordeal feels like she learned nothing. Then again, Kon’s curtailing of Mima, and her final note of uncertainty and self-destructive ambition might also be an accurate, tragic reflection of stardom. Although Kon introduces problems of representation by how he depicts his condemnation of the troubled relationship between public and private spaces, Perfect Blue remains thought-provoking and undeniably powerful, if not entirely emotionally satisfying. Nevertheless, its remarks about entertainment culture, celebrity worship, virtual environments, and toxic fandom supply an incisive prophecy about how these factors continue to invade every aspect of our lives.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested, commissioned, and posted on Patreon. Thanks for your support, Julian!)

Bibliography:

Gardner, William O. “The Cyber Sublime and the Virtual Mirror: Information and Media in the Works of Oshii Mamoru and Kon Satoshi.” Canadian Journal of Film Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 2009, pp. 44–70. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24411782. Accessed 15 April. 2021.

Newitz, Annalee. “Magical Girls and Atomic Bomb Sperm: Japanese Animation in America.” Film Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 1, 1995, pp. 2–15. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1213488. Accessed 15 April 2021.

Osmond, Andrew. Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist. Stone Bridge Press, 2009.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review