Penelope

By Brian Eggert |

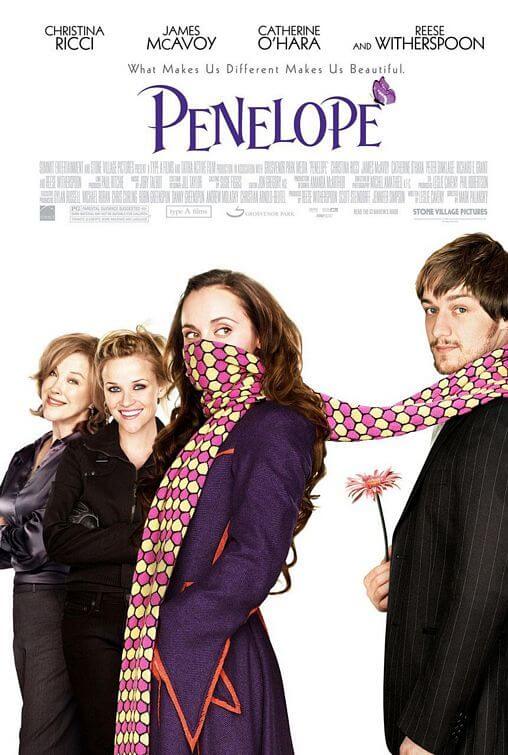

Penelope is a modern fairy tale, existing in an allegorical reality where curses, witches, and true love run rampant. We follow the noble Wilhelm family. Generations ago, they were stricken with the horrible promise that the next Wilhelm girl would be grotesquely deformed. Their curse is realized when Penelope (Christina Ricci) is born with a pig’s snout and ears. Since the nose cannot be surgically altered, her aristocratic parents, rather than deal with the shame, fake her death and wait until she’s of age to find a blue-blood husband—her marriage to whom will break the curse.

Based on the book by children’s author Marilyn Kaye, the adaptation comes from Everybody Loves Raymond writer Leslie Caveny with plenty of good-natured laughs. Those of us familiar with Homer’s The Odyssey will remember Penelope as the wife of Odysseus; she fends off suitors while waiting for her long-lost love to return home. The film’s Penelope isn’t so lucky, as suitors jump out windows at the sight of her snout. Her misguided parents Jessica (Catherine O’Hara) and Franklin (Richard E. Grant) work to find someone, anyone from money to wed their daughter, meanwhile subjecting Penelope to rejection after horrible rejection, oblivious to how it makes her feel when men repeatedly scream in terror at her appearance.

Seeking to expose the Wilhelms’ upper-class urban legend, a sleazy reporter named Lemon (Peter Dinklage) has long-attempted to get a photo of the rumored pig-girl. Teaming with frightened would-be suitor Edward Vanderman Jr. (Simon Woods), Lemon pays down-and-out rich boy Max (James McAvoy) to pose as Penelope’s solution, infiltrating the Wilhelms’ home to capture a photo of their daughter. Max is too kindly for such exploits, however; he engages Penelope for the first time in endearing conversations—the sort where it’s clear to everyone, except the two involved, that the participants are falling in love. But Max’s participation in Lemon’s scheme is exposed, causing traumatic results. And so, after twenty-five years of believing herself ugly, feelings which her oftentimes cruel parents do little to dissuade, Penelope runs away to find herself, her face wrapped up in a scarf to hide her secret.

Reese Witherspoon, who also produced the picture, appears in a brief cameo as Penelope’s know-all friend Annie, whom she meets after escaping home and exploring the world. Witherspoon’s conspicuous yet abbreviated presence distracts more than it helps, making us wonder why this Oscar-winning actress has but a few lines and no purpose, other than to introduce Penelope to her delivery-girl Vespa. But frankly, Penelope doesn’t need any support, which, I suppose, is the film’s point.

Most impressive here are the film’s comic performances, notably the cartoonishly superficial mother character handled by O’Hara—a hugely underestimated actress nowadays, as she exaggerates every emotion to match the film’s satirical edge. Dinklage, Grant, and McAvoy all do excellent-if-quirky work, garnishing Penelope with its fairy tale tone. But it’s Ricci’s show with her quiet draw and those large, expressive eyes, which admittedly make Penelope sort of cute in an Island of Dr. Moreau way.

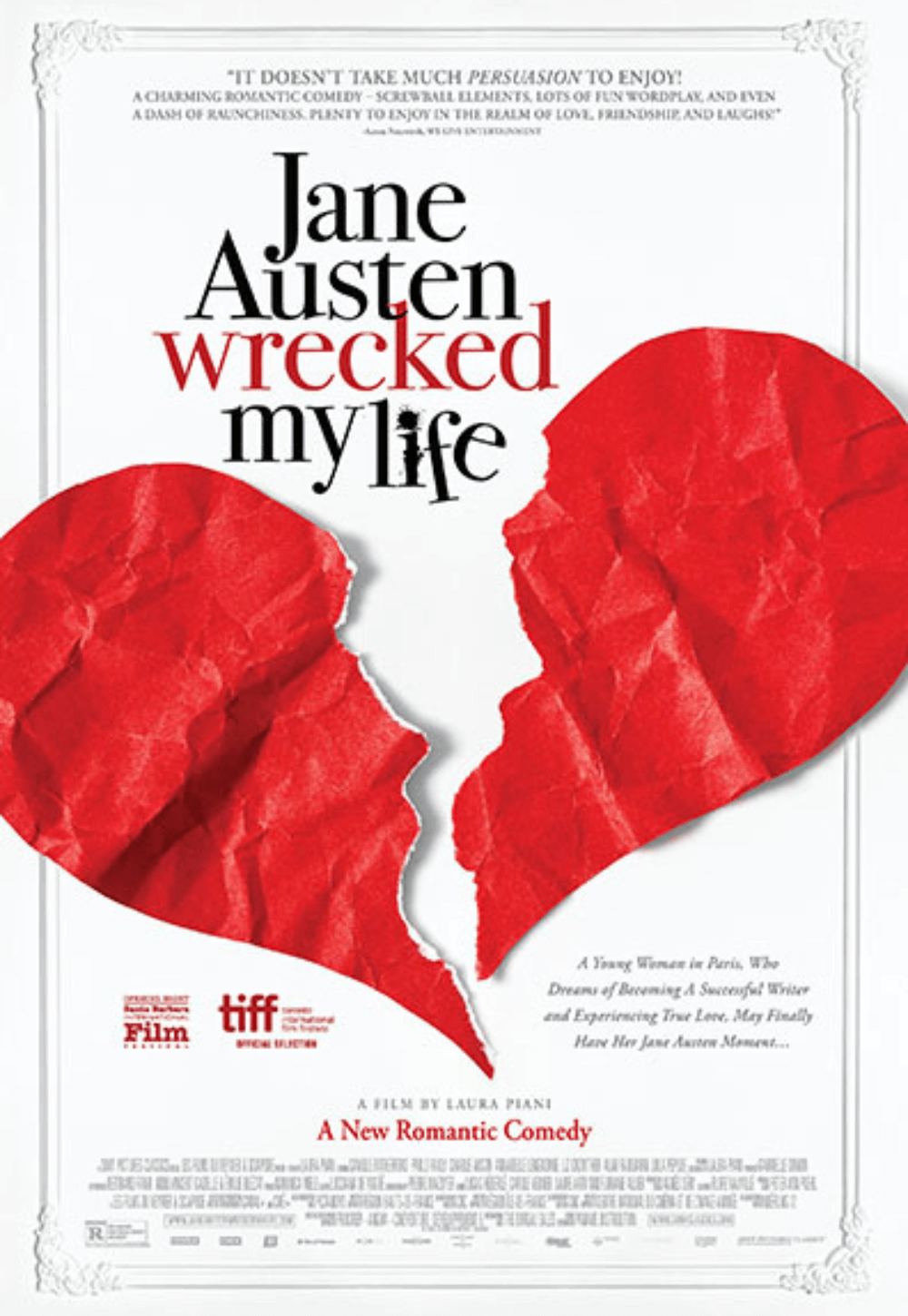

Languishing in production hell, the film wrapped shooting more than two years ago in England. Frequent moviegoers have endured the film’s much-changing trailer ever since. Some trailers suggested Ricci would remain behind her purple and yellow-dotted scarf for the duration, while others liberally showed off her snout. Doubtful marketing executives knew exactly how to sell a movie where the main character has a pig nose, especially when her name isn’t Babe.

In the end, when Penelope’s nose eventually goes back to “normal” as a result of her newfound self-love, we realize that the film’s message, albeit inspiring for youths in the audience, sells itself out. Granted, Penelope does learn to love herself in pig snout form initially, but then the story opts to change her, making her “beautiful” in the end. Now that she’s just like everyone else, her self-confidence is no longer remarkable. I’d like to imagine a version where Penelope lives happily ever after with her pig snout intact, giving hope to those of us in the audience who don’t look like Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, or have facial features resembling swine.

Despite that minor quibble, Penelope is a delightful and imaginative little movie, adorned with plenty of good-intentioned morals. First-time director Mark Palansky, former assistant director to Michael Bay (don’t let that frighten you), sharpens the material with a few wild camera angles and classy production design. In the best way possible, we imagine a storybook closing when the end credits begin to roll, avoiding any cheesy Nickelodeon-type traps a production such as this could have easily fallen into. Plentiful with idiosyncrasies recalling Enchanted, this offbeat tale of love and self-discovery has surprising originality and unquestionable charm.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review