Pearl

By Brian Eggert |

Pearl opens on a storybook farm soaked in rich colors and splashy titles, images that recall Douglas Sirk’s melodramas of the 1950s. Director Ti West’s deliberate camp aesthetic returns moviegoers to the scene of the crime from X, distributed by A24 earlier this year. That throwback slasher, set in Texas during the 1970s, found the elderly Pearl horny and bloodthirsty for an amateur adult film crew, whom she slaughtered and fed to the resident alligator—something she’s been doing to passers-by for years, apparently. But West’s prequel isn’t the blend of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) and Boogie Nights (1997) that X was; it’s not a blazingly gory exploitation romp that delights in testing our limits—and for that, it’s refreshing to see that West has other things on his mind besides repeating a proven formula. Still, some viewers may take time to adjust to Pearl’s pacing and tone, which conveys Pearl’s disturbed mind through dream sequences and a heightened visual style. While it’s an origin story that adds to the expanding X mythology, it’s also a showcase for the considerable talent of Mia Goth. She reprises her role as Pearl and delivers an unforgettable performance.

West and Goth conceived of the prequel while waiting to shoot X in New Zealand at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. With West in quarantine for two weeks before his admittance into the country, the director and star produced a script and pitched their add-on idea to A24. The studio greenlit the prequel to everyone’s surprise, before even seeing X completed. And so, West and company shot the two features back-to-back, both headlined by Goth in two roles, three very different performances, at one location, set in two distinct periods. This sort of inspired stunt aligns with A24’s modus operandi, giving inventive filmmakers license to try something out of the ordinary. West doesn’t overplay his classical stylization in this case, despite the wipe transitions and the booming score by Tyler Bates and Tim Williams. Cinematographer Eliot Rockett’s radiant lighting, reminiscent of the extreme lights required for three-strip Technicolor cameras, renders bright and luminous colors, suggesting the palette of The Wizard of Oz (1939). Whereas X was gritty, sweaty, and dilapidated, Pearl appears heightened and optimistic, immersed in the character’s subjectivity and desire to become famous.

The last time we saw Pearl, it wasn’t under the best circumstances—her head was crushed under the wheel of a pickup truck by would-be porn star Maxine (also Goth), who was headed for Hollywood stardom. The prequel takes place 60 years earlier, in 1918, and the title’s oddly sympathetic young psychopath lives with her parents on the same farm. In X, the older woman took out her sexual repression and regret about a life not lived to its fullest on the porn crew. In Pearl, the wannabe ingénue dances in the mirror and performs for farm animals, announcing, “Y’all see me for who I really am… A star!” Pearl does love a good audience—except for the damn goose, whose disapproving honk incites Pearl to silence it with a pitchfork. Pearl’s murderousness starts small, with animals. But later, she finds bigger targets, namely those who hold her back from pursuing her dreams: her taskmaster mother (Tandi Wright) and invalid father (Matthew Sunderland), who needs regular care. She even resents Howard (Alistair Sewell), her husband, who’s off fighting the First World War in Europe. She imagines him coming home, and, at the same instant she squeezes an egg in her fist, he detonates in her mind. When Pearl’s mother later tells her, “Malevolence is festering inside you,” we can see her point.

The last time we saw Pearl, it wasn’t under the best circumstances—her head was crushed under the wheel of a pickup truck by would-be porn star Maxine (also Goth), who was headed for Hollywood stardom. The prequel takes place 60 years earlier, in 1918, and the title’s oddly sympathetic young psychopath lives with her parents on the same farm. In X, the older woman took out her sexual repression and regret about a life not lived to its fullest on the porn crew. In Pearl, the wannabe ingénue dances in the mirror and performs for farm animals, announcing, “Y’all see me for who I really am… A star!” Pearl does love a good audience—except for the damn goose, whose disapproving honk incites Pearl to silence it with a pitchfork. Pearl’s murderousness starts small, with animals. But later, she finds bigger targets, namely those who hold her back from pursuing her dreams: her taskmaster mother (Tandi Wright) and invalid father (Matthew Sunderland), who needs regular care. She even resents Howard (Alistair Sewell), her husband, who’s off fighting the First World War in Europe. She imagines him coming home, and, at the same instant she squeezes an egg in her fist, he detonates in her mind. When Pearl’s mother later tells her, “Malevolence is festering inside you,” we can see her point.

Those familiar with X may not acquire much new information about its subject in Pearl, which could be a stand-alone film. This isn’t a prequel like many in the horror genre today that seek to demystify movie maniacs by shedding too much light on them or explaining a catalyst to the killer’s behavior. Instead, the film serves as a character study, more interested in Goth’s performance and ability to give Pearl layers. To be sure, Pearl suspects that something is wrong with her, that she’s been isolated too long because of the Spanish flu pandemic. West recreates a familiar period of mask requirements and fear of infection that lingers from COVID-19 (in reality, the Spanish flu was much worse). All that time alone has made Pearl yearn for attention, even the wrong kind: she bathes in front of her incapacitated father, then touches his face and squeezes his throat before asking, “Are you still in there?”—ignoring his terrified eyes. But mostly, she wants to escape farm life. When sent into town for her father’s prescription, she visits the local moviehouse and takes swigs from the bottle of morphine. There, she meets a handsome projectionist (David Corenswet), who keeps European stag movies in his celluloid collection and self-servingly tells her, “Don’t forget to live your life too.” Could this theater employee help her escape the farm? Even though she feels guilty about cheating on her husband, her shame is minimal next to her desperate yearning for attention, approval, and freedom.

The events in Pearl show a disturbed young woman who deserves empathy but soon passes a point of no return, and the arc is both tragic and monstrous. There’s a pattern where Pearl’s genuine hopes are thwarted by situational factors, her mother who sees Pearl as the embodiment of her own failure, and her growing insanity. Consider this microcosmic example: Pearl dances with a scarecrow in a cornfield, and the girlish distraction soon goes overboard. She open-mouth kisses the straw man, imagines it with the projectionist’s face, then shouts at him that she’s married, but then mounts him anyway. Indeed, Pearl loses herself in passionate moments. Her mania comes to a head over an upcoming dance competition—which she learns about from Mitzy (Emma Jenkins-Purro), her sister-in-law—that might be Pearl’s ticket out of town. The eventual audition is a delirious and deranged look into the character’s mind. Still, by that time, Pearl has already gone too far—and yet, the viewer cannot help but root for Pearl to succeed, even though the events in X tell us that she’ll never leave that farm, no matter how bad she wants it.

Viewers familiar with Sirkian melodramas and classic horror will appreciate the visual flourishes and nods throughout. But Pearl isn’t about West’s tendency in his other films for sometimes oppressive homage or making a horror-inflected postmodern commentary on the period—similar to what Todd Haynes did on Far From Heaven (2004). Rather, it plays more like Monster (2003), the biography of serial killer Aileen Wuornos that earned Charlize Theron an Oscar. Goth gives a comparable performance here—easily her best yet—revealing a complex and broken mind with notes of manic and maniacal behavior. However, when she unleashes a prolonged, gut-wrenching wail after her audition, Pearl’s emotional response is open-hearted and unnerving (her reactions often have that effect). The same is true when Pearl roleplays with Mitzy, pretending she’s Howard to express her anxieties honestly. The result is a masterful six-minute monologue and confession, captured in a single, immersive take that teeter-totters between lunacy and heartbreak. It’s the scene that makes Pearl more than just a proto-slasher spin on West’s earlier film and elevates it to something special—a film about how everyone dreams of something better, but few attain their dreams. That’s the crippling but commonplace disappointment on display in Pearl, which has already been compared to Joker (2019), except the anti-hero in West’s film is far more agreeable.

Viewers familiar with Sirkian melodramas and classic horror will appreciate the visual flourishes and nods throughout. But Pearl isn’t about West’s tendency in his other films for sometimes oppressive homage or making a horror-inflected postmodern commentary on the period—similar to what Todd Haynes did on Far From Heaven (2004). Rather, it plays more like Monster (2003), the biography of serial killer Aileen Wuornos that earned Charlize Theron an Oscar. Goth gives a comparable performance here—easily her best yet—revealing a complex and broken mind with notes of manic and maniacal behavior. However, when she unleashes a prolonged, gut-wrenching wail after her audition, Pearl’s emotional response is open-hearted and unnerving (her reactions often have that effect). The same is true when Pearl roleplays with Mitzy, pretending she’s Howard to express her anxieties honestly. The result is a masterful six-minute monologue and confession, captured in a single, immersive take that teeter-totters between lunacy and heartbreak. It’s the scene that makes Pearl more than just a proto-slasher spin on West’s earlier film and elevates it to something special—a film about how everyone dreams of something better, but few attain their dreams. That’s the crippling but commonplace disappointment on display in Pearl, which has already been compared to Joker (2019), except the anti-hero in West’s film is far more agreeable.

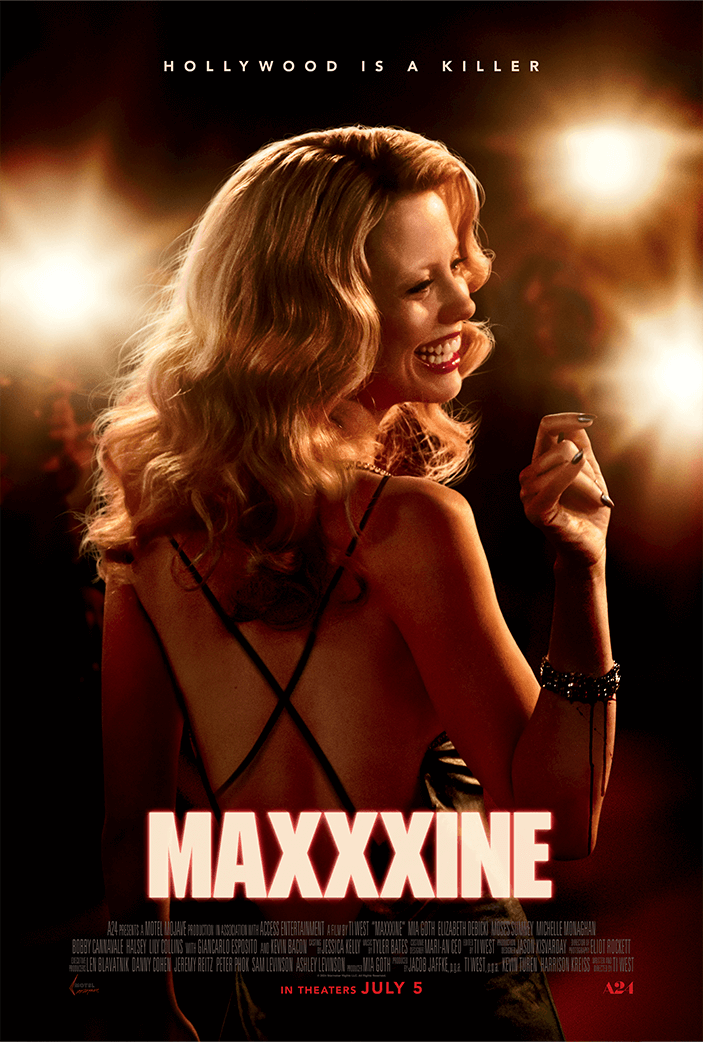

Just as the end credits of X contained a teaser that promised Pearl would be coming soon, A24 teases the not-yet-filmed MaXXXine after the prequel’s credits, which will mark an “X-traordinary” trilogy for West. Working alongside Goth, the filmmaker delivers another superb horror film that never sacrifices the audience’s investment for kitsch. Although West’s filmography contains examples of period and horror homage that sometimes distracts from the narrative—see The House of the Devil (2009) and The Innkeepers (2012), both of which I’ve come to appreciate more in recent years—his stylistic choices serve Pearl’s stagelike view of the world. Goth, too, sells every emotion, from the most basic human desire for love to Pearl’s unsettling outbursts when someone “goes cold.” And then there’s the doozy of a last shot, in which Pearl smiles, unblinking in alternately funny and horrifying waves, and holds it for two-and-a-half minutes during the end credits. After she wishes on a shooting star to escape, Pearl’s dashed hopes are crushing and, much to the viewer’s astonishment, go beyond horrific and into the realm of harrowing sadness.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review